Author Guest Post: James Goulty

Today on the blog we have a guest post from Pen and Sword author, James Goulty.

Eyewitness Korea is out now.

Reflections on the ‘Forgotten War:’ Korea, 1950-1953

Today Korea is often dubbed the ‘Forgotten War.’ Even in America, where the military involvement was larger than in Britain, there is a palpable sense that Korea has been overshadowed by later conflicts, notably Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan. Likewise, it was fought in the wake of the Second World War, when people were still recovering from that trauma, and this led to Korea being overlooked. Yet, it was a pivotal conflict in the Cold War, and could have led to a Third World War, especially when China entered the fray in November 1950. It is now known that North Korea played a significant role in instigating the war, a charge it would probably deny, when it invaded its southern neighbour on 25 June 1950. At the time in the West this was widely perceived as nothing more than a centrally orchestrated plot by the Kremlin.

Fears over the war escalating and Cold War politics, led President Harry Truman to term Korea a ‘police action,’ something resented by veterans because it led others to consider theirs wasn’t a ‘proper war.’ Korea was not a benign campaign, but rather a brutal civil war, that became internationalized and witnessed the West confront Communism under the banner of the United Nations. Alongside America, South Korea and Britain, troops were deployed from the Commonwealth, and countries as diverse as Ethiopia and Turkey. These served under American command, a mixed blessing, and because the British Army experienced tensions this contributed towards the formation of 1st Commonwealth Division in 1951.

Across the peninsula acres of Korean ‘real estate’ was damaged, and many cities were severely bombed. Millions of North and South Koreans perished, and the war generated numbers of refugees, almost invariably fleeing from the North to the South, not the other way around. These presented a pitiful sight to soldiers from UN nations. During the 1950s Korea was underdeveloped by Western standards, and American troops were incredulous at seeing oxen pull ploughs etc. The summers were hot and dusty and heat exhaustion was a threat. In contrast, winters were viciously cold. The ‘Siberian Express,’ a wind blowing down from the north penetrated uniforms, froze weapons, hampered vehicles and generally made life unbearable. British troops, whose winter kit was completely inadequate during 1950-1951, found it especially hard. Frostbite was another hazard. During the Chosin Reservoir campaign in the north east of the peninsula, for example, U.S. Marines and others faced horrendous conditions, where extreme cold was as much an enemy as the Chinese.

Both sides committed atrocities. Civilians were sometimes killed deliberately or accidentally as ‘collateral damage.’ Many troops witnessed traumatic events, such as the death of comrades, and understandably weren’t keen to talk about their experiences on returning home. This added to the sense that Korea has been ‘forgotten.’ Britain lost around 1000 personnel during the war, mostly from the army. American casualties were greater, around 37,000 killed and approximately 103,000 wounded many of them seriously. Artillery, mortars, mines, small arms and edged weapons all created appalling injuries to the human body, plus some returned with less visible scars as psychiatric casualties. The suicide rate among American veterans has been notably high. Some troops even attempted to find a way out by giving themselves a self-inflicted wound (SIW).

Another chilling factor was the apparent acceptance by the enemy of high casualties. This was highlighted by the Chinese employment of mass attack tactics, when invariably entire platoons or companies would target a particular point, so that to British and American defenders it appeared that they were confronted by wave after wave of enemy. One American officer notably likened the tactic to ‘assembly on the objective.’ A corollary of this was that troops perceived they were faced by fanatics who advanced regardless of casualties. It even seemed as if some enemy troops went into action unarmed and were expected to use the weapons of fallen comrades. Under these conditions defenders could develop trigger fatigue from killing or become embroiled in horrendous close combat where grenades, bayonets, entrenching tools and even fists were used.

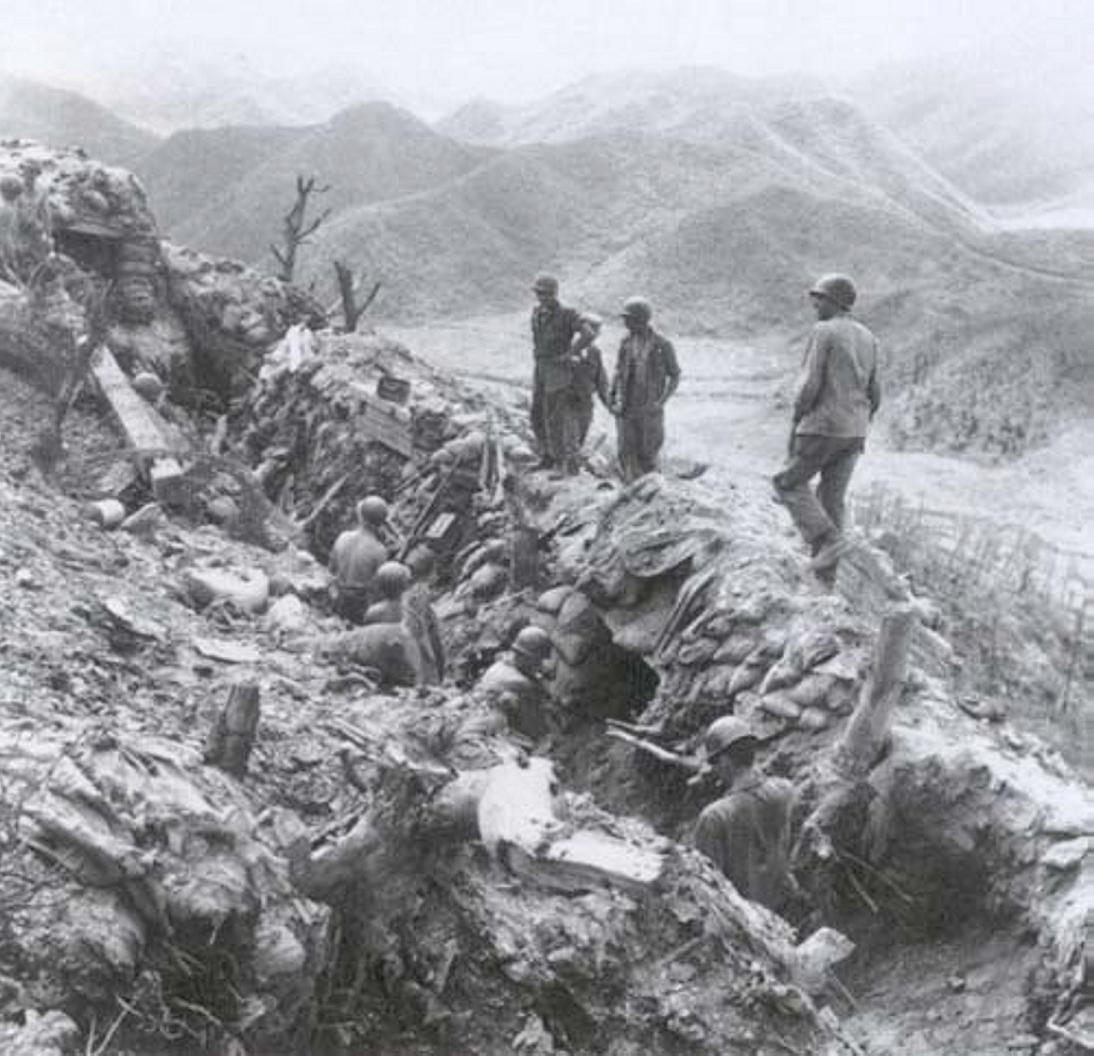

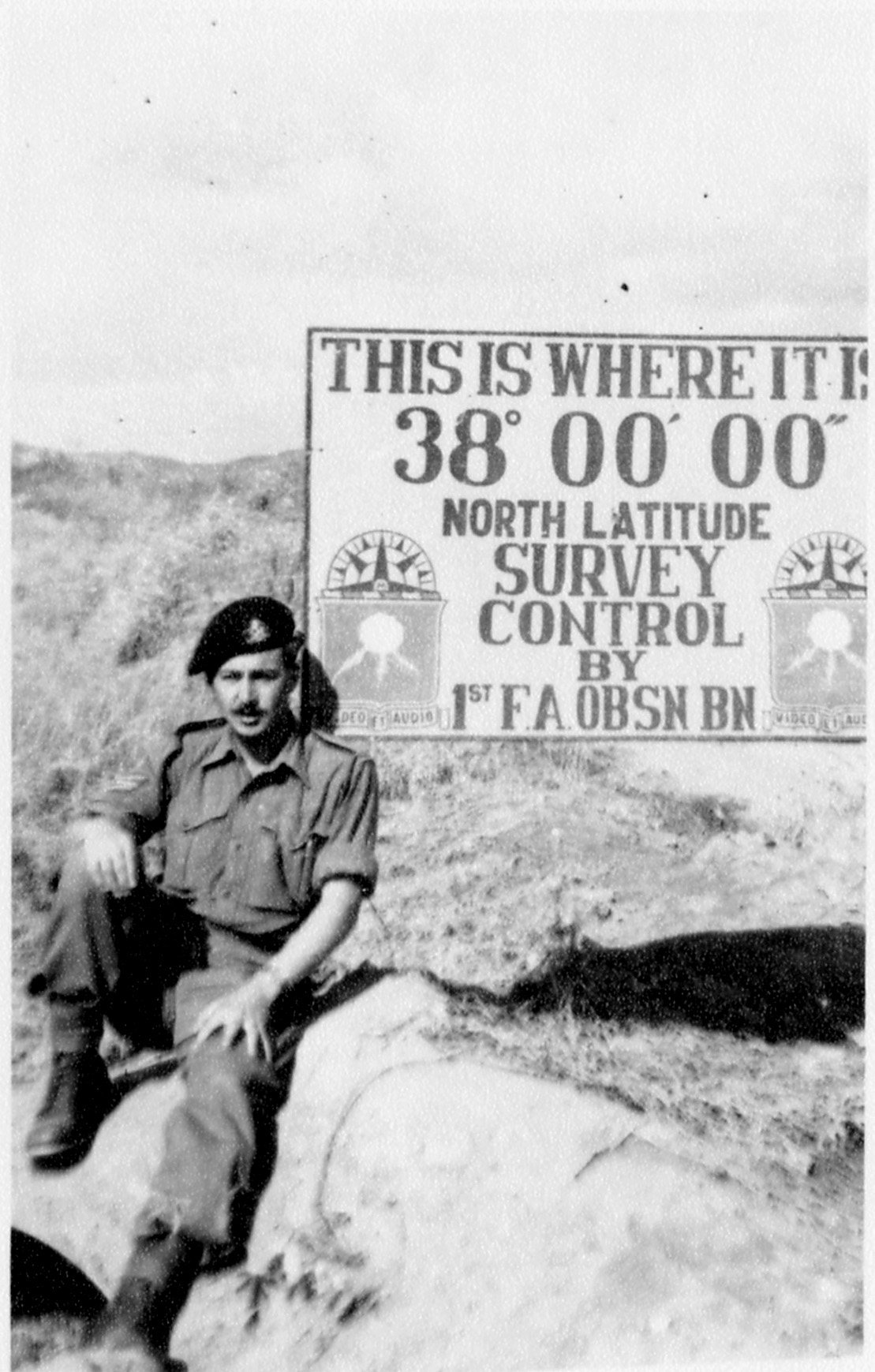

Likewise, the North Koreans had much in common with the Japanese Army during the Second World War, albeit they were equipped and trained along Soviet lines. British troops who’d fought in Burma during 1942-1945, found that again in Korea during 1950-1951 they faced a determined enemy who used ‘Banzai’ style charges and flurries of grenades at close quarters, and favoured infiltration tactics against flanks and rear areas as opposed to head on assaults. Early on, especially for understrength and inadequately trained American troops, fresh from easy garrison life in Japan, such tactics were difficult to counter. While desperate fighting occurred to hold the Pusan Perimeter in summer 1950, it appeared as if a ‘Far East style Dunkirk’ evacuation might have to be launched. However, as history demonstrates the Pusan Perimeter was held, and UN forces went onto the offensive, while the audacious amphibious landings at Inchon occurred. Subsequently, under General Ridgway Communist action was countered and a series of limited offensives launched by UN forces, before fighting effectively solidified around the 38th Parallel. From late 1951 until the July 1953 ceasefire, conditions were reminiscent of the First World War, with both sides maintaining static defensive positions backed by artillery. For the men at the front patrolling and raiding became major activities, along with bloody battles for key terrain features. Neither side was prepared to go for all out victory, and instead pursued a limited war while peace talks made faltering progress. This sense of stalemate was difficult to accept, especially for Americans used to defeating an enemy in the field, and contributed further to Korea being ‘forgotten’ because it appeared as if little was happening at the battlefront.

If you’d like to read more about the Korean War please look for:

Thanks, James Goulty