Fact or Fiction: Common Misconceptions of Historical Witchcraft

Guest post from author Frances Timbers.

Historical witchcraft of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is one of the most misunderstood phenomena in twenty-first century popular culture. Radio and television announcers frequently raise the topic of the ‘witch-craze’ in Europe as the calendar approaches Halloween each year. They state that these disturbing events happened during the ignorant and superstitious era commonly known as the ‘Dark Ages’. In fact, burning victims at the stake was popular between 1450 and 1750, during the Renaissance. To put things into perspective, this was the same time that Galileo was discussing how the earth orbited around the sun and Francis Bacon was espousing empiricism and experimentation. So much for the alleged progress of the scientific revolution!!

Another misconception, promoted by Monty Python and others, is that the Roman Catholic Church’s notorious Inquisition was responsible for tracking down members of an underground cult of witches. Although Christian doctrines and beliefs are largely responsible for transforming the idea of sorcery into heresy, which contributed to the intensity of witchcraft prosecutions, the Inquisition was actually quite lenient when it came to persecuting alleged witches. The Inquisition was primarily concerned with rooting out heretics, such as Jews and Muslims recently converted to Christianity, as well as the new heresy of Lutheranism. The Spanish Inquisition was quite sceptical about the alleged capabilities of those accused of witchcraft. Alonso de Salazar Frías, an influential Inquisitor, argued that there was no proof of witchcraft, resulting in a very cautious approach to accusations. The Roman Inquisition was also conservative, particularly concerning the reality of the sabbat, which prevented the mass prosecutions experienced in Germany.

The numbers of victims is also often inflated. Historians estimate that there were between 90,000 and 110,00 trials resulting in 40,000 to 50,000 executions, which is no small number. However, some feminist authors compared the witch hunts to the Holocaust and stated that as many as nine million women were terrorised. Such numbers are pure fabrication. The other misconception concerning this statement is that the persecution of witchcraft was a systematic and misogynistic program of searching out female social deviants. While it is true that the majority of the people executed for witchcraft were women (as high as 80%), it was not a program of woman-hunting. In some areas, more men than women were accused. Nevertheless, for many historical reasons, including gender ideologies, women were more likely to be suspected as witches.

Connected to the idea of woman-hunting is the belief is that the women accused of witchcraft were wise women, healers, and midwives, practising alternative medical techniques. This is not the case. Midwives were generally respected members of society, often licensed by local authorities, and seldom came under suspicion. Male midwifery did not come into vogue until the eighteenth century, long after the decline of witchcraft prosecutions. Midwives were not targeted to make room for males in the delivery room. Occasionally, women and men who practised the healing arts did come under suspicion, but cunning men and women were not routinely accused as witches. In fact, midwives and cunning folk were more often employed to assist authorities in a witch trial.

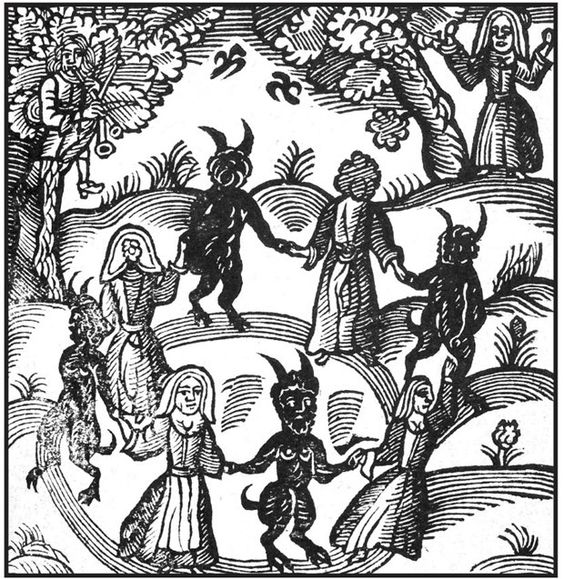

Judges, lawyers, and clergy in the early modern period frequently imagined Satanic meetings of witches attended by the Devil himself. However, there is no evidence to support the alleged gathering of witches at a sabbat. In the 1920s, the Egyptologist and folklorist Margaret Murray initiated the theory that the victims of witchcraft accusations were members of a pre-Christian fertility cult that had been driven underground. This theory, although debunked by historians, has been widely propagated by modern Wiccans and other neopagans. Rather than continuous worship of an ancient religion, the modern practice of Wicca was developed in the 1950s. Gerald Gardner constructed a nature-based spiritual practice from an eclectic blend of sources and a large contribution from the work of Aleister Crowley.

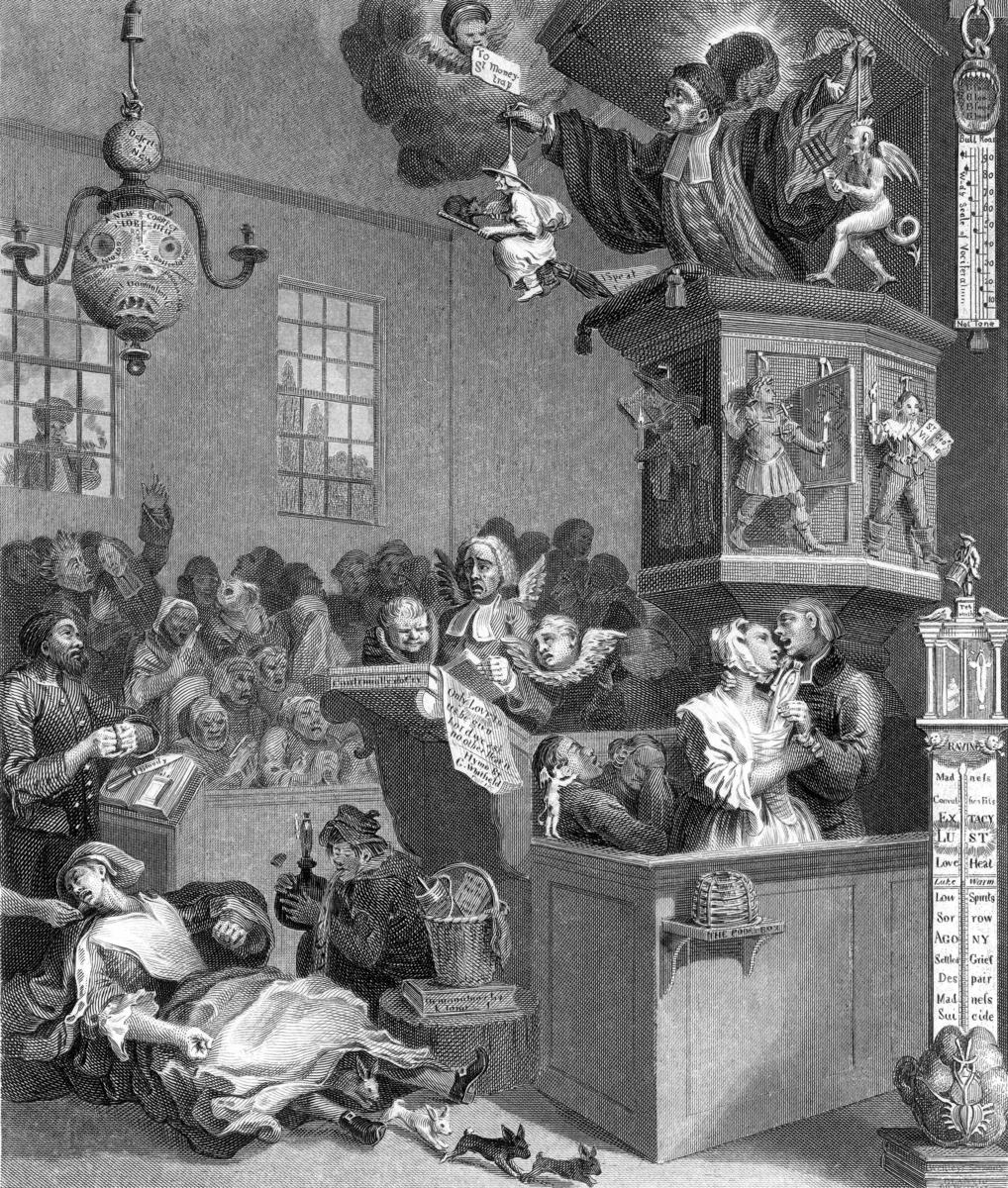

The concept of magic and witchcraft existed long before the height of prosecutions in the early modern period and belief in the supernatural continued long after the decriminalisation of witchcraft in the eighteenth century. Over time, a stereotypical image of the Halloween witch developed, as seen in the illustration by William Hogarth in 1762. Magic is a timeless topic and the celebration of Halloween brings the figure of the witch to the public’s attention every year. In the West, we are largely free from any repercussions concerning supernatural beliefs, but in some parts of the world, the witch is still a powerful figure, who is feared and persecuted.

A History of Magic and Witchcraft is available to order here.