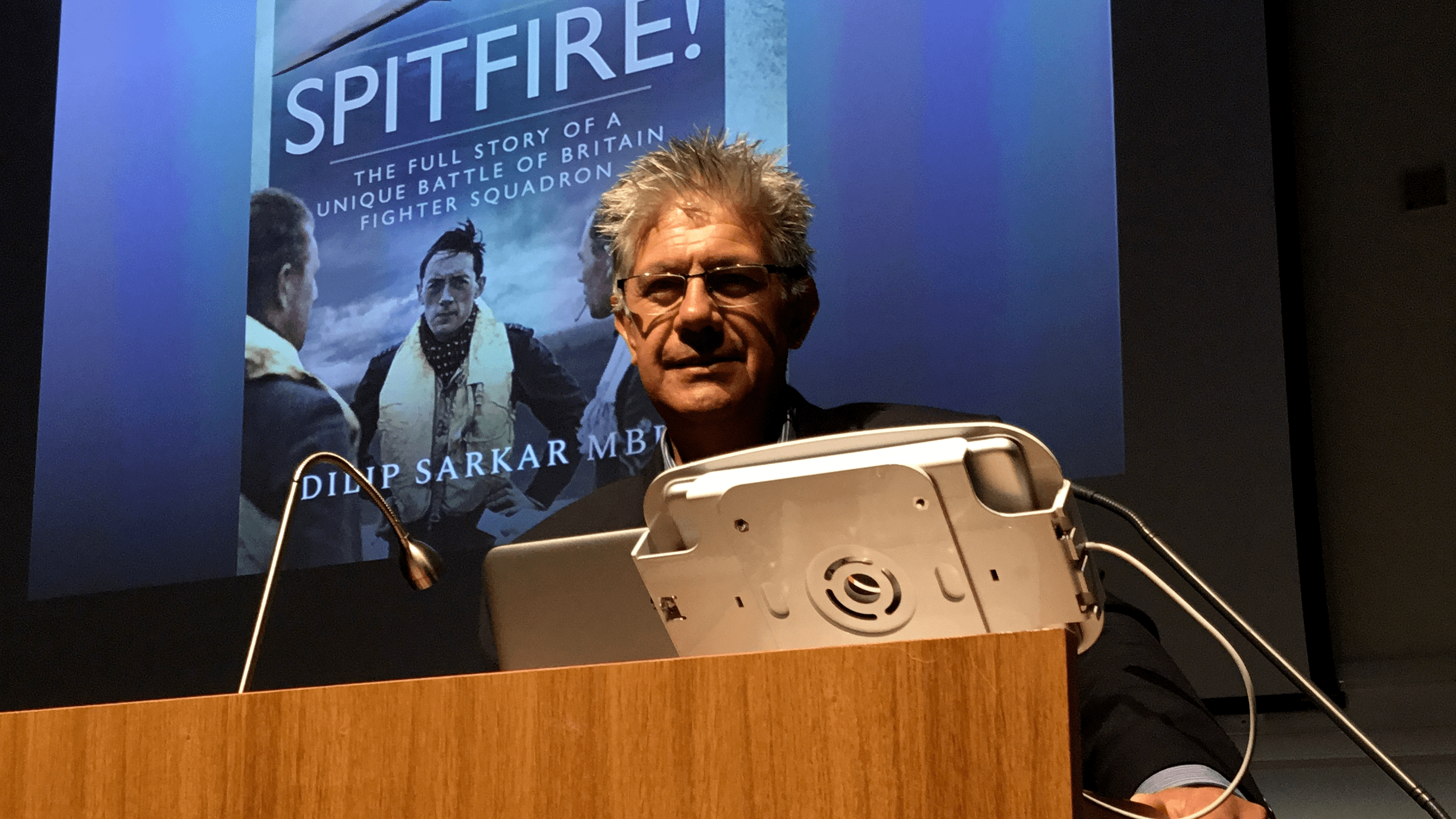

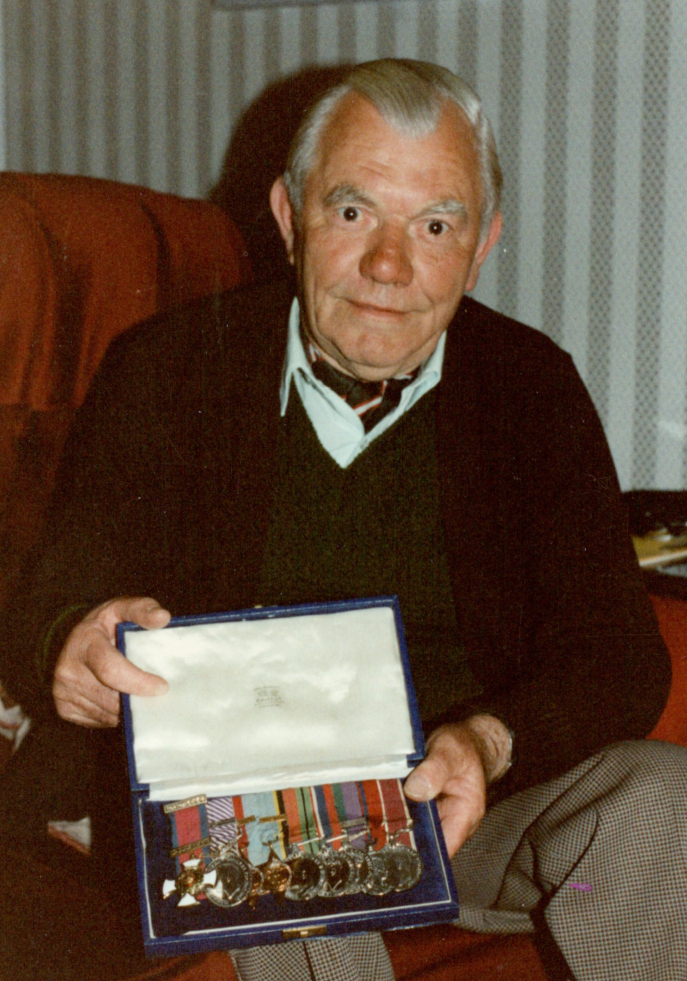

Meet the author: Dilip Sarkar MBE FRHistS

Driven by his passion to research and share the stories of casualties, and record the human experience of war, Dilip Sarkar MBE is a best-selling author whose work is highly regarded globally. In this Q&A Dilip, tells us more about his upcoming books!

What initially fascinated you about the Second World War?

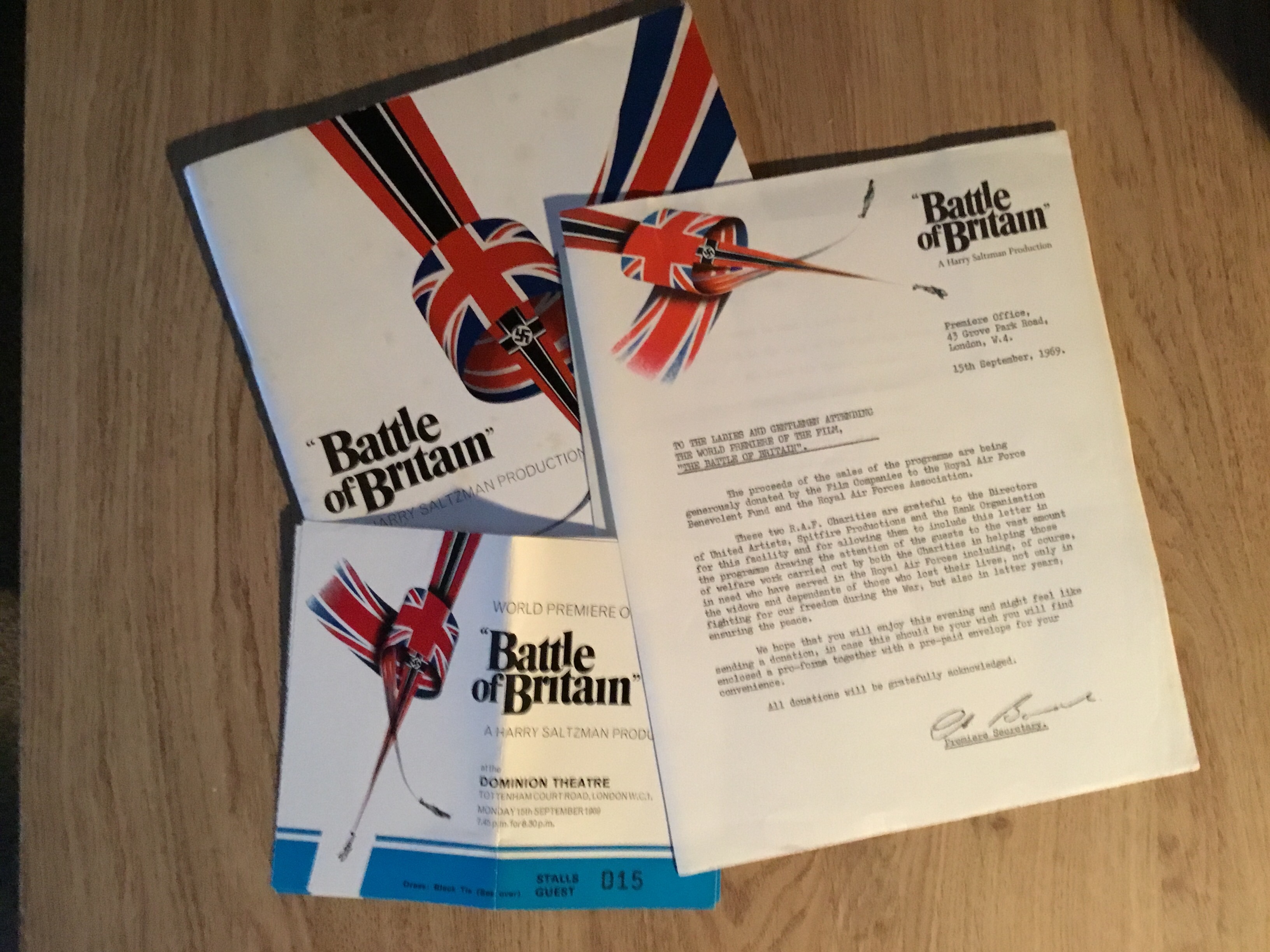

Growing up in the 1960s and 70s, the Second World War was omnipresent, you just couldn’t get away from it. Boys were indoctrinated by warlike toys and reading material, and it was the golden era of war films. Family members had experienced the war, some as combatants, as had your neighbours, teachers, all kinds of people you came into contact with. The war was constantly discussed to some degree or other in all environments, or so it seemed to me. My uncle made large-scale model Spitfires, and as an infant I was fascinated by them, making my first Airfix model aged four! When I was eight, the 1969 film Battle of Britain was released following a long promotional campaign. I watched it spellbound. By then I already knew the Battle of Britain story, and Spitfires and Hurricanes were, of course, my favourite aircraft. The great thing about Battle of Britain is that real aircraft were used – and lots of them – and it was in colour. Inspirational!

I came to realise, however, that the war may not have been quite the glorious and exciting experience that comics like the Victor and Warlord would have us believe. For example, whilst our neighbour, a wonderful man called John Anthony, who was a navy veteran of both world wars, readily talked about his wartime experience, my own maternal grandfather – a Grenadier wounded and captured in bitter fighting on the road to Dunkirk – refused to discuss the subject under any circumstances. I was also aware that my maternal great-grandfather was missing from the First World War, and well recall my little old great-grandmother, who was ancient, or so seemed to me, talking of the hardships she faced living in the country, a mile from a water pump, raising a young family alone. Here, then, was a human experience clearly adrift from the Boys’ Own version. When I was ten, my father, a Quaker, stopped on our return journey from London to show me service graves at Moreton-in-the-Marsh. I was profoundly moved, walking between the rows of white headstones. We all knew about famous heroes like the legless fighter pilot Douglas Bader and Dambuster Guy Gibson – but these men, pilots, navigators and air gunners, killed whilst training on Wellington bombers, were just names on a stone. I wanted to know who they were, what they looked like, where they were from, all about them. It was the start of a lifetime’s obsession.

When I was eighteen, I realised that some of the pilots killed during the Battle of Britain were the same age as I was then – which struck a chord. That year, 1980, the encyclopaedic Battle of Britain: Then & Now was published – which for me was life-changing. Here were photographs of those killed during the summer of 1940 – to whom we all owed so much – alongside pictures of their graves, some of the privately-owned plots and memorials overgrown, which I thought appalling. Here too were stories of aircraft recoveries by enthusiasts – aviation archaeologists – providing an opportunity to actually uncover untold stories and reach out and actually touch the violent past. I was hooked, and immediately began my own research into local connections with the Battle of Britain. Then, in 1985, when I was a young police officer at Malvern, my pal Andy Long mentioned that a Polish Spitfire pilot had baled out just outside the town, but was reported missing six months later. That was the lightbulb moment. We traced and interviewed eyewitnesses, located the crash site, and formed the Malvern Spitfire Team to research the history and recover the Spitfire’s remains. Most importantly we decided to erect a memorial to the pilot, which although he, Flying Officer Franek Surma, was not killed there, we somehow thought appropriate as he had no known grave. This was unveiled in September 1987 by two Polish Battle of Britain pilots and back then was the only memorial to an individual Polish fighter pilot in the UK. My research into that particular Spitfire’s story involved identifying other pilots who had flown her, R6644, tracing and interviewing survivors and the relatives of those who were killed. And that, then, is really how it all started.

You have two upcoming books with Pen and Sword, can you tell us about them?

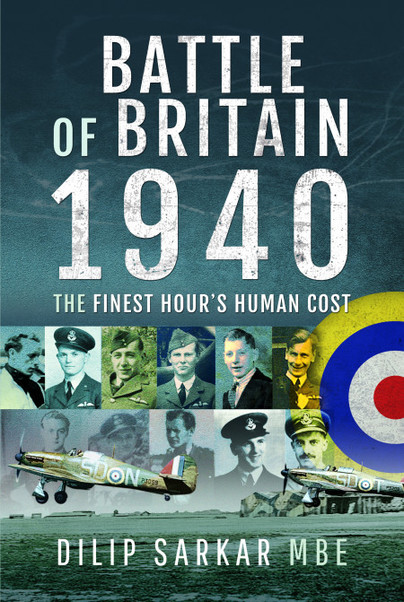

Battle of Britain 1940: The Finest Hour’s Human Cost

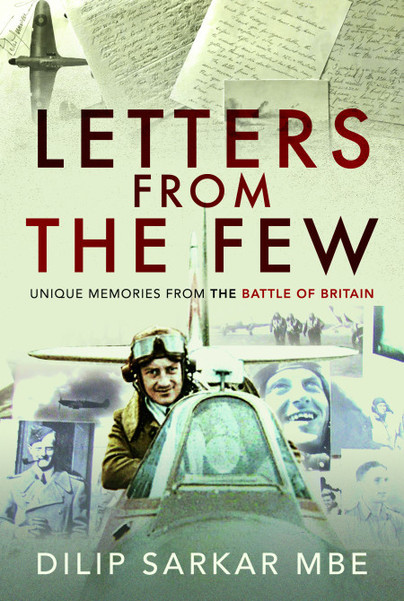

Letters from the Few: Unique Memories of the Battle of Britain

What inspired you to write these?

My work has always been inspired and informed by the human experience of war, and what I believe is a crucial need to record and share survivors’ accounts. Moreover and as previously explained, I am deeply moved by the stories of casualties and how families remain affected by these losses all these decades later. The dead, of course, have no voice, so this side of my work is about reconstructing their often all too short lives and sharing what is often hidden, personal, history that would otherwise go unrecorded. So, for this year’s Battle of Britain 80th anniversary, I wanted to produce two special books – one telling the stories of casualties, the other sharing survivors’ experiences. So in these two books, both aspects of my work are encapsulated.

Who will the books appeal to?

Obviously in the first instance military aviation enthusiasts, but these books are very much about people, not the technical aspects of the aircraft involved, so will appeal to a much wider general readership, as my titles generally do.

What research have you done? Have you been able to access any primary source material?

All of my research is original, going back to primary sources. For example, in respect of the casualty research, that means obtaining individual service records, medal citations, combat reports, squadron records, and – most importantly – tracing the families of those who failed to return. In that endeavour I have to acknowledge the invaluable help I receive from genealogist Michelle Baverstock, who kindly traces families for me and has yet to fail! Then, it is a matter of contacting and achieving the families cooperation, often involving many emails, telephone calls and, prior to the pandemic, travelling around the UK to interview people. One of the most interesting stories id that of Pilot Officer Martyn Aurel King – the youngest of the Few – killed over Southampton in the same action in which Flight Lieutenant James Brindley Nicolson won his Victoria Cross; Aurel, as he was known in the family, had a most unusual upbringing, his parents being missionaries in China.

In this book, I have not just looked at RAF aircrew. Also included is the story of a German Me 109 pilot shot down by a Spitfire over Biggin Hill, civilians killed when the Supermarine factory at Southampton was bombed, and a merchant seaman – the latter story a bit of an eye-opener, to say the least – but no spoilers!

Letters From the Few is based upon my personal correspondence with Battle of Britain aircrew, which began during the mid-1980s and is voluminous. I knew many members of the exulted Battle of Britain Fighter Association as personal friends over many years, throughout which we frequently corresponded and met at my book launches, symposiums and exhibitions. This correspondence now represents a unique archive, these letters from the Few documenting their wartime experiences, and more, providing a unique insight into the experience and personalities of these august veterans. These experiences have to be contextualised and events explained in more detail, so that means reviewing all kinds of documentary evidence, including aircraft movement cards, squadron diaries, combat reports, Civil Defence records, RAF Intelligence Reports, information from both sides regarding combat losses and claims, all kinds of primary sources.

What was the hardest part about writing these books?

The problem is the inexorable march of time. When I began this kind of research, survivors were a plenty and we were dealing with the widows, siblings and children of casualties. Today, only one Battle of Britain pilot is known to be alive – a far cry from when I dined with over 100 of the Few at Battle of Britain Fighter Association annual reunions back in the day – and the ‘children’ of casualties, if still with us, are now at least eighty, and most close relatives are deceased. This is why my archive of interviews and correspondence with survivors and close relatives is now such an important primary source. So today, in terms of casualties families, we are often dealing with distant relatives who know very little, and rarely a family member who actually knew the casualty in life. Consequently, whether any worthwhile information on a casualty remains in family hands depends upon whether someone has taken up the mantle of family archivist, collating and preserving material. It is increasingly frequent now to trace a family only to find that nothing, not even a photograph, exists of the casualty concerned, although sometimes you can still strike gold and find a treasure trove of previously unshared material – as we have in Battle of Britain 1940.

The other thing that was difficult was revisiting my correspondence with the Few – because these men were close personal friends, despite our difference in age. As all are now deceased, re-reading their letters was an emotional journey in itself, which often brought a tear to my eye. Wonderful people.

Have you been able to use original photographs in the books? How did you acquire these?

Absolutely. Again, my research has always involved copying the personal photographic collections of survivors and the families of casualties, so all of my books are proliferated with previously unpublished images – and these two are no different.

What part of the books or your research are you most proud of?

I am a retired police detective and so have spent my professional life investigating, analysing evidence and interviewing people – and dealing with the suddenly bereaved. These skills have enormously helped my historical research and ability to approach and communicate with people. Families are always treated with the utmost sensitivity and respect, and it does make everything worthwhile to see their delight when ancestors’ stories are published and shared, and to receive positive feedback. Sharing the survivors’ experiences and stories of forgotten heroes is what I do, and yes, I am proud of what has been achieved over the years, which was recognised in 2003, when I was made an MBE for ‘services to aviation history’, and in 2006 when I was elected to the Fellowship of the Royal Historical Society, both of which things are a very big deal.

What do you plan on writing next?

I have just finished three books revolving around my great friend Air Vice-Marshal Johnnie Johnson, officially the RAF’s top-scoring fighter pilot of the Second World War, two of which will be published by Pen & Sword this autumn, the other early next year. I am currently writing, with the family’s cooperation, a biography of the great South African fighter pilot and leader, the inspirational Group Captain ‘Sailor’ Malan – who became an anti-apartheid activist post-war but sadly died prematurely. I also have to write Missing in Action: Finding the Fallen of the Second World War, and several other Battle of Britain related books, but more about those another time. I have to say that the author-publisher relationship is crucial to success. My publisher, Martin Mace, and I have become very good friends and work together perfectly, immediately recognising the potential in ideas and taking those forward to fruition. We have much more up our sleeve – so watch this space!

Battle of Britain 1940 is available to preorder here.

Letters from the Few is available to preorder here.

Find out more on Dilip’s website here.