Störflug – The Bombing of ‘The Faithful City: 3 October 1940

Author guest post from Dilip Sarkar MBE FRHistS FRAeS.

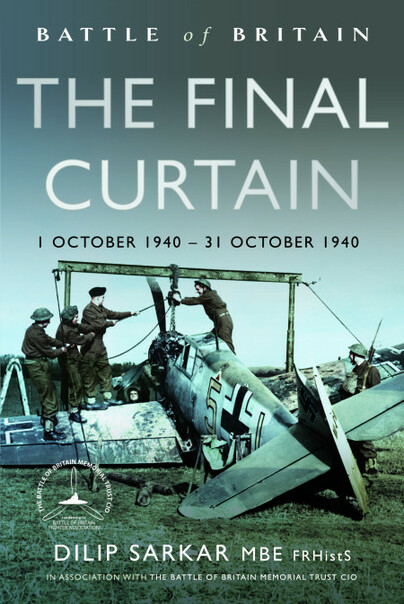

Publication of The Final Curtain: 1 October 1940 – 31 October 1940 is the seventh volume on my eight volume, unprecedented, one-million-word narrative, which is the Battle of Britain Memorial Trust’s official history. The first volume, The Gathering Storm, investigates the background and wider scenario of both sides, whilst volumes two – seven inclusive are an extremely detailed, day,-by-day chronicle of the battle, covering every raid and action fought, including the oft neglected operations of Bomber and Coastal Command, the Royal Navy, and, of course, the German perspective. Furthermore, the effect on the Home Front and civilian morale is included, therefore providing a truly rounded view of how the Battle of Britain was fought and affected everyone involved. Fortunately, the innumerable first-hand accounts included I began collating forty years ago, and, as none of The Few are known to be alive today, these are unobtainable now.

The brief was not to produce an academic text but a lively, yet detailed, narrative, engaging the reader whilst using in-text referencing, rather than thousands of distracting footnotes. After a lifetime of research, the eight volumes took two years to actually write – and The Final Curtain covers the final month of battle, in addition to an evidence (not myth) based analysis of the Spitfire and Hurricane’s combat record – which may surprise many. The final volume, Battle of Britain Remembered, looks at the aerial conflicts place in remembrance, memorialisation, literature and film, whilst covering the emotive and controversial of ‘The Missing Few’ – those pilots known to still remain with their crashed aircraft in Kent – and concluding with a directory of key museums, memorials and sites of interest. The Final Curtain, however, covering the last thirty-one days of battle, concludes the day-by-day narrative and is, therefore, a landmark title. That being so, let us look here at the not so obvious…

It is easy to think of the Battle of Britain in terms of hordes of German aircraft bombing London; certainly the enemy’s decision to bomb London round-the clock, starting in the afternoon of 7 September 1940, was a turning point, providing 1respite for 11 Group’s airfields, and the fighting over the capital on 15 September 1940 convinced Hitler that Fighter Command could not be defeated in time for a seaborne invasion to go ahead in 1940. Be that as it may, we must remember that owing to the reach of air power, the whole of the British Isles was within range of German bombers – and there was much fighting away from London, over the West Country, for example, which accommodated various aircraft factories, and the huge attacks on north-east England on 15 August 1940, which saw Luftflotte 5 defeated in a single day. On 30 September 1940, the He 111s of KG 55 intended to attack Westland Aircraft at Yeovil, but, owing to cloud obscuring the target actually bombed nearby Sherborne town centre in error – and the Germans’ losses during that raid made clear the fact that such casualties could no longer be sustained. Already, due to heavy losses, the Ju 87 Stuka had been withdrawn from the daylight battle, and now the He 111 was moved over to night bombing. By day, it was decided that raids would only be carried out by Ju 88s, operating singly on suitable days of bad weather, or by formations of up to Gruppe strength (three Staffeln, or squadrons), heavily escorted by fighters. Indeed, the last major daylight raid of the Battle of Britain was not directed at London but Westland Aircraft, when, on 7 October 1940, the Ju 88s of II/KG51 sallied forth – but missed the factory, hitting Yeovil town instead. Going forward, the air fighting saw high-flying Me 109 nuisance raiders indiscriminately bombing London and the south-east, and the fighters of both sides clashing at high altitudes. The point is, though, that not only London suffered – and now let us look at a most unlikely event: the bombing of Worcester in the West Midlands, on 3 October 1940.

Growing up in Margaret Road, St John’s Worcester, in the 1960s, I vividly recall adult neighbours talking about ‘The day the MECO was bombed’, this being the Mining & Engineering Company in Bromyard Road, about a mile away. By all accounts, these eyewitnesses said, a lone Ju 88 appeared from low cloud, orbited the ‘Faithful City’ several times in broad daylight before attacking the MECO from low level, causing great damage and civilian casualties. For an air and military minded child, this was fascinating – and now, after all these years, I have unearthed the full story in German records.

The attacks by lone Ju 88s were known as Störflug, harrasing attacks targeting airfields and the aircraft industry. These were only flown by experienced crews, who studied their target before attacking in bad weather, using cloud to reach, attack and leave the target without being intercepted. During the night of 2/3 October 1940, the weather over England significantly deteriorated, substantially reducing the daylight operations of both sides – but these conditions were perfect for the raids by lone Ju 88s.

At 0700 hrs, the Meteorological Office recorded at Birmingham a light NNE wind, and a low layer of stratus cloud at 5,700 feet. The weather generally was ‘dull, rainy and rather cold’. The base of 10/10ths cloud sank to just 500 feet, visibility out of it was just 500 yards. Such conditions were completely unsuitable for the high-altitude fighter sweeps and fighter-bomber raids of the previous day, but were conducive to nuisance raids by lone Ju 88s targeting airfields and the British aircraft manufacturing industry. Such incursions, therefore, were the day’s main event, and between 0630 and 1230 hrs, nine single enemy aircraft crossed the East coast between Yorkshire and Harwich.

After mid-day, a succession of raids crossed the coast, the enemy flying between 1,000 – 1,800 feet. Amongst these was the Ju 88 of Leutnant Otto Bischoff II/KG77 (6th Staffel), which took off from Laon at 1110 hrs (continental time), again according to Schambak, tasked with attacking Coventry’s Daimler factory, which produced parts for aero-engines. Fourteen Ju 88s of I/LG1 headed for London between 1228 and 1545 hrs (continental time), but cloud obscured the target so not hits were noted.

According to Fighter Command’s Daily Intelligence Summary, ‘In two cases aircraft penetrated far inland, one flying to Worcester, where bombs were dropped, to Birmingham and Wellingborough which were also bombed. The second crossed the coast at Bawdsey, flying to North Weald and Debden. Bombs were dropped near North Weald from 1,000 feet’.

The provincial south-west Midlands city of Worcester, situated some thirty-five miles south-west of Birmingham, forty miles SSW of Coventry, would have little direct experience of war – but that it was bombed on 3 October 1940 emphasises how the reach of air power had made the Home Front, everywhere, the front line. Straddled across the River Severn, Worcester’s primary industries were pottery, light engineering and clothing manufacture. Nonetheless, like everywhere else, Worcester had been scrutinized by Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft, and possible targets were coded accordingly: the Worcestershire Regimental barracks at Norton, petrol storage tanks at East Diglis, government buildings at Whittington, and Worcester’s Zivilflugplatz, or civilian airfield, at Perdiswell – the wartime home of 2 Elementary Flying Training Sschool.

On the West bank of the Severn lies the Worcester suburb of St John’s, where, in Bromyard Road, adjacent to the main western railway line, was the MECO premises. The busy factory manufactured various equipment for the mining industry, and in 1940 was sub contracted by the Air Ministry to produce surge drums for barrage balloons. Early precautions against air attack had been taken, shelters for workers being constructed, and in conjunction with Worcester Corporation the establishment of an auxiliary fire station, and direct landline communication with the city’s Guildhall in respect of air raid warnings. At a cost of £800, the works had also been camouflaged.

In Worcester, 3 October 1940, had started like any other day.

The MECO’s office staff had left for lunch at 1215 hrs, a few men clocking out early, although. The main workforce’s mealtime was not scheduled until 1230 hrs – just before which a lone Ju 88 descended from cloud over Worcester and circled above the Cinderella Works and Alley & MacLellan factory in Bromyard Road. Margaret Woodward was sixteen and working at her first job as a shorthand typist in the office of the Quality Cleaners, in Bromwich Road, St John’s. Hearing the aircraft passing very low overhead, the typists ran out of the office where they heard gunfire. Only a few yards from where they stood, bullets spattered into the ground: ‘The markings of the plane were visible and it was very frightening – we rushed back indoors!’

Twelve-year-old Terry Hulme was playing with school friends in hop fields towards Bransford: ‘We heard aero engines, very low, looked up and saw a Ju 88 approaching at 300 feet from a direction of Malvern. It whizzed over us, pooping off a few rounds of machine-gun bullets, so we ran like hell for home, passing an old gent who was walking his dog; when told that the aircraft was German he didn’t believe us until he looked up at the bomber and saw the plainly visible black crosses. He then took off at a right rate of knots and left his dog standing! The aircraft was actually so low that the crew were clearly visible in the erspex nose. On reaching home I yelled to mother to take to the Anderson shelter at the bottom of our garden in the Broadway. We were halfway there when a stick of bombs dropped onto the MECO works causing an explosion and a sheet of yellow flame shot up. We were nearly blown over by the blast’.

Lesley Adams was actually working in the MECO’s riveting shop:-

‘Someone shouted “Jerry gone over!” but we all laughed as we thought it was a leg-pull. He said “It’s true, I’ve seen the crosses!”, so we all went out, and out of the gloom came this aircraft, and true enough there were the big black crosses. Looking up I saw a bomb drop and fall towards us. I shouted “God, strewth!” and ran. The bomb went through the roof of the assembly shop, bounced through a brick wall and exploded adjacent to MECO Lane and near houses in Happy Land West. There was another which skidded and hit some houses. Then it was absolute chaos. I ran across the railway line and up the embankment. The bomber then opened fire at the factory as it flew on towards Laugherne Brook. Shaken, I then made my way back to the chaos’.

Having been lofted from such a low altitude, the bombs ricocheted, one SC250KG bomb had crashed into the machine shop, carving its way out through the factory’s East wall. Mr Sadler was working in there at the time, and remembers that ‘The bomb hit a girder, bounced and shot outside before exploding’. The canteen was demolished and there seven men were killed; three were seriously injured, amongst them the canteen attendant, Doris Tindall, who lost an eye; sixty other civilians suffered minor wounds. Had the attack occurred a few minutes later when the factory en bloc were queuing to clock out, or taking lunch in the canteen, the death toll would have been far greater. Sadly, amongst the seven MECO dead was young Terry Hulme’s father, William, a foreman blacksmith and old servant of the company, having moved down from Sheffield during the late 1920s to help start the Worcester firm. Another fatality was Albert Williams, forty-two years old, who had lost both legs above the knees when fighting with the Worcestershire Regiment at the Battle of Gheluvelt in 1914. Nevertheless, he became mobile on prosthetic limbs, and even rode a motor-cycle, and when the Second World War broke out he was employed at the Austin works in Longbridge; ironically, being unable to get about quickly during air raids, he decided to move to Worcester, where such attacks were less likely.

The second SC250KG bomb narrowly missed the factory, bounced off a concrete base, across Happyland West, a suburban street, and exploded in adjacent Lambert Road: some 300 houses were damaged in total. A child, Margaret Wainwright, also tragically lost an eye, standing in the window awaiting her father’s arrival home for lunch at the time. Margaret Woodward, who lived in Bromyard Road, remembers that ‘Our window frames were never quite the same fit afterwards, although the criss-crossed sticky tape with which we all covered our windows had saved the glass’.

To the great credit of all involved, full production resumed at the damaged Worcester site a week later.

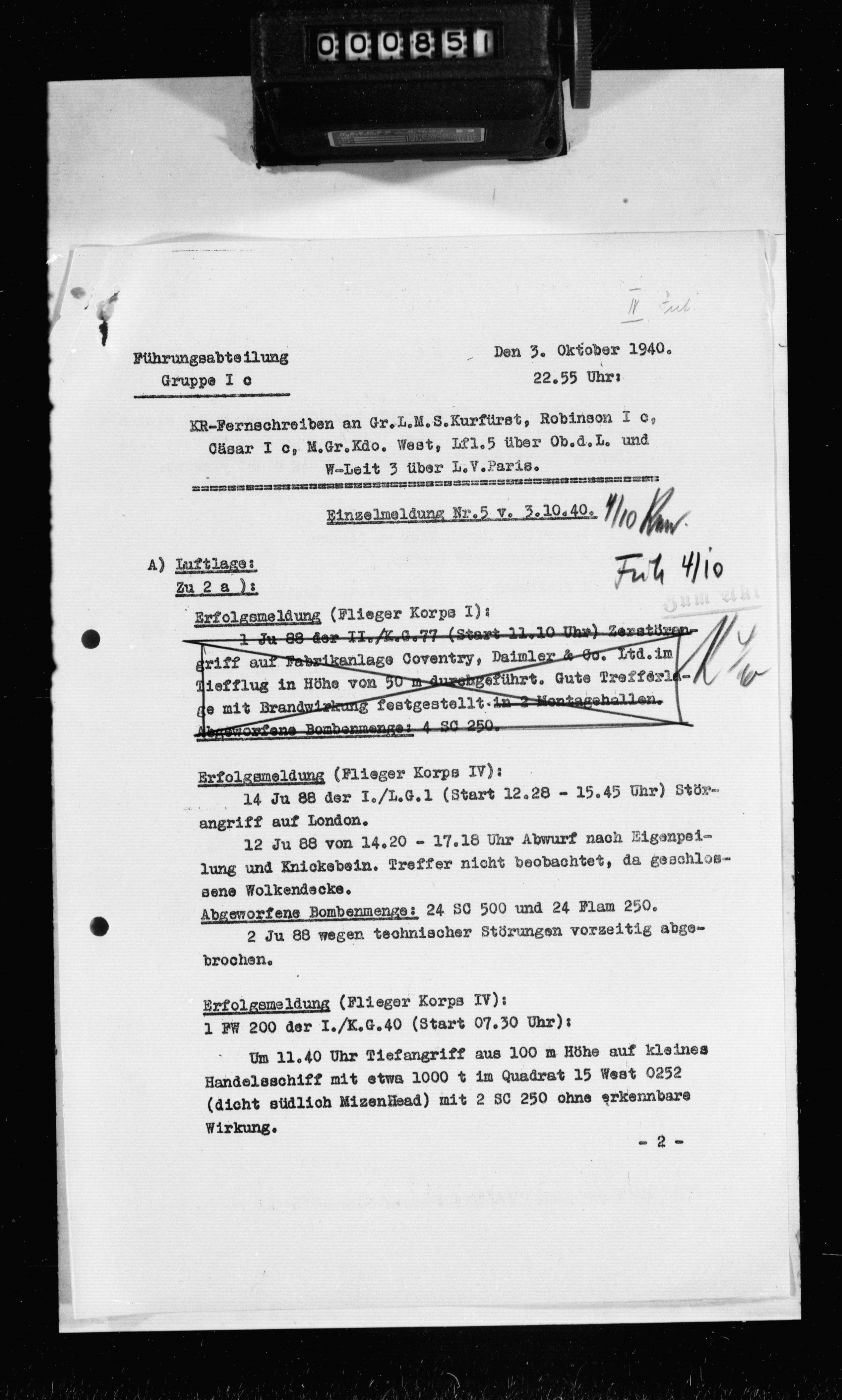

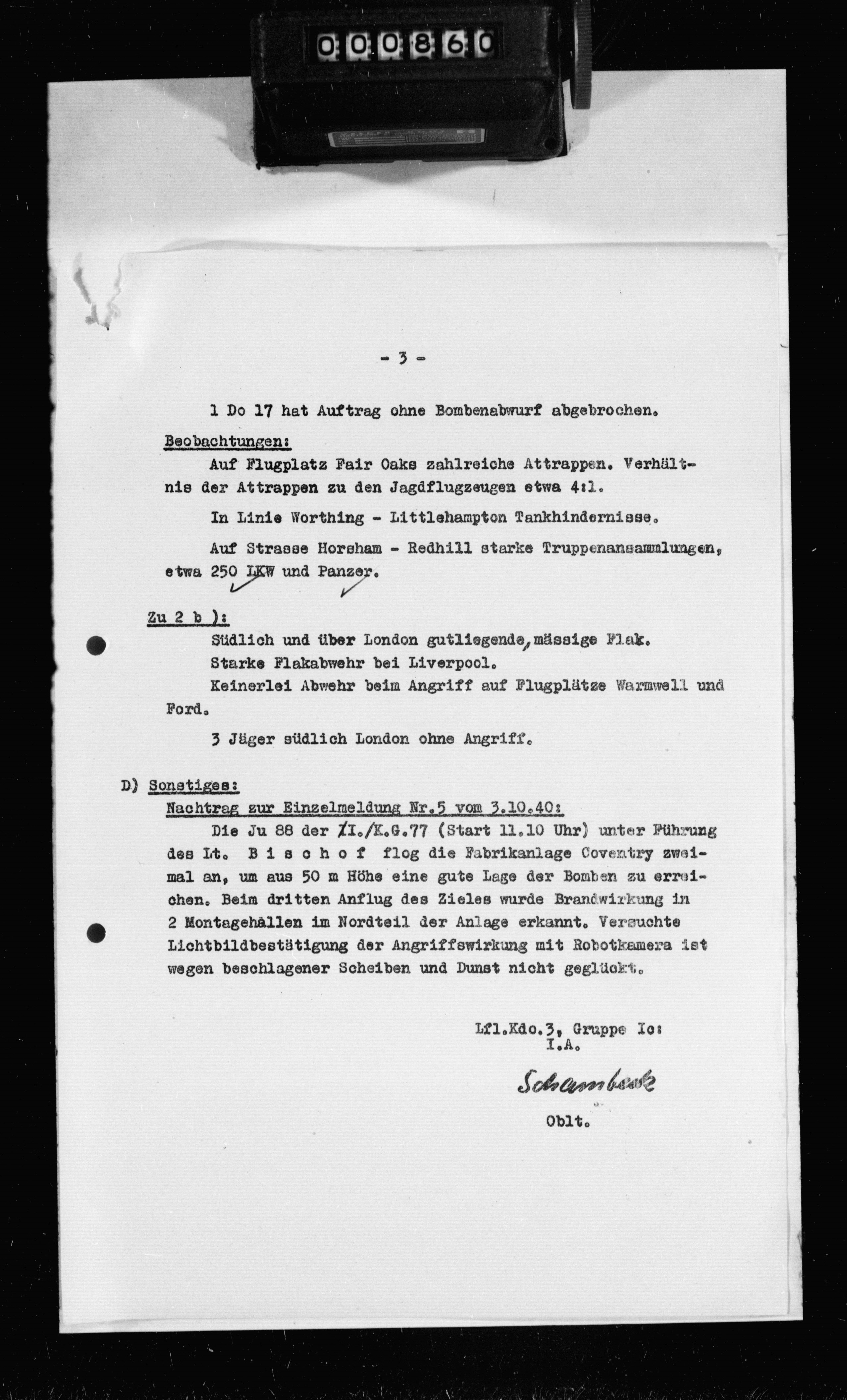

Who was responsible for the MECO raid? The answer lies in page three of Oberleutnant Schambak’s after action report: –

‘The Ju 88 of I/KG77 (start at 1110 hrs) under the command of Leutnant Bischoff flew to the Coventry factory twice in order to get a good location for the bombs from a height of 50m. During the third approach to the target fire effects were detected in two assembly halls in the northern part of the facility. Attempted photographic confirmation of the attack with a robot camera failed due to fogged-up lens and haze’.

Leutnant Otto Bischoff, however, had not attacked ‘the Coventry factory’ but mistakenly bombed the MECO – such a navigational error being not uncommon, especially given the bad weather. Although mistaken regarding the target, Bischoff’s attack was audacious, orbiting Worcester several times in broad daylight, at low-level, before successfully attacking the MECO and returning safely to France. As the only time loss of life was caused by bombing in the so-called ‘Faithful City’, the incident would be well-remembered by survivors and remains indelibly etched into Worcester history and folklore.

Born in Essen on 24 September 1915, Otto Bischoff was an experienced Kampfflieger, and would go on to fight in Russia and in the Mediterranean theatre. Having first received both the Iron Cross first and second class, on 15 December 1941 Bischoff was awarded the German Cross in Gold. By 1 April 1942, promoted to Oberleutnant, Bischoff was Staffelkapitän of 4/KG77, based at Comiso, Italy, which was heavily engaged in the siege of Malta. At 2145 hrs that night, however, whilst on a mission to attack Allied shipping in Valetta’s Grand Harbour, Bischoff’s Ju 88 was intercepted and shot down into the sea by Pilot Officer Oakes and Sergeant Walsh in their 89 Squadron Beaufighter. Bischoff and his crew, namely Oberfeldwebel Karl Eppensteiner (navigator/observer), Unteroffizier Wilhelm Kruse (Bordfunker), and Oberfeldwebel Josef Schmidt (air gunner), all remain missing (whether this was the same crew with whom Bischoff attacked Worcester on 3 October 1940 cannot be ascertained). By the time of his death, the twenty-six-year old Oberleutnant Bischoff had flown over 225 combat missions – for which august feat he was posthumously awarded the coveted Ritterkreuz (Knight’s Cross) on 3 May 1942.

Returning to 3 October 1940, the War Room Daily Summary records that at 1440 hrs ‘The Gas Light and Coke Company was bombed at Banbury… and production was suspended for four days’. Again according to Oberleutnant Schambak, a lone Do 17 was responsible for this raid on ‘a gasworks situated 60 km NNW of London – most likely at Leighton Buzzard – with ten SC250 bombs. The same crew also attacked an army depot with remaining ten SC250 bombs. The gas works were set alight’. Again, the German crew was incorrect regarding the location attacked, which was actually in Banbury, thirty-five miles north-west of Leighton Buzzard.

None of these lone raiders were intercepted by Fighter Command, however, owing to the bad weather, although one raider was brought down by ground fire whilst attacking Hatfield aerodrome. 10 Group, though, flew thirty-two patrols, in response to thirty-two individual enemy aircraft operating over theWest Country and SW Midlands, without a glimpse of even one bandit. 12 Group HQ recorded that ‘By day, enemy activity was on a larger scale than usual although for the most part the raids consisted of single aircraft. Weather conditions were ideal for the “hit and run” raids as there was very low cloud throughout the Group area. After 1330 hrs the weather became worse and no more fighter action was taken’

3 October 1940, was, for sure, a rare day, one on which there were no interceptions, or aerial combat claims by either side – one of only three such days throughout the entire Battle of Britain (the others being 17 August 1940 and 31 October 1940).

After all these years, then, and as a direct result of this project, we now know the full circumstances of the MECO raid – and who was responsible, the answer being found amongst Luftwaffe operational records captured in 1945, copies of which I purchased from an online American archive. Having previously scoured German archives and records for years without success, I had, in truth, given up on ever discovering the enemy side of events – but, clearly, if you never, ever, give up, sometimes you can be rewarded with a little luck….

© Dilip Sarkar MBE FRHistS FRAeS BA(Hons), 2025

Order titles here.