Did Catherine of Braganza Bring Marmalade to England?

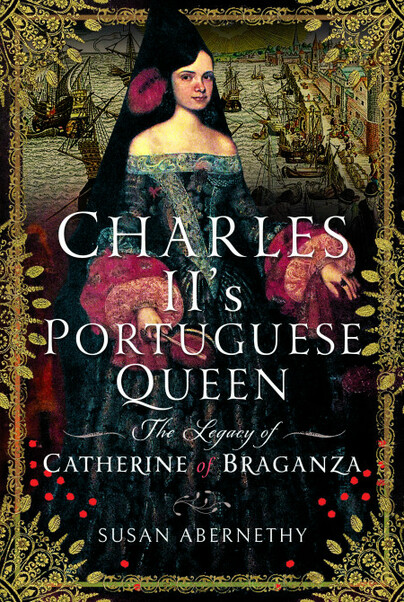

A guest post by Susan Abernethy.

It is a common belief that Catherine of Braganza, the Portuguese princess who married King Charles II, brought marmalade to England and popularized the consumption of the preserve. Is this true?

Historical records indicate the first shipment of marmalade came in a Portuguese merchant ship in the year 1495, during the reign of King Henry VII. Shortly thereafter, the same product arrived from Spain and Italy. This is also in the beginning of the celebrated era of Portuguese seaborne exploration in search of a route to India. In Portugal, the local dialect went through a transformation as the Mozarabic word for quince, malmâlo, became marmelo, the modern Portuguese word for the fruit.

A version of the term marmalade appears in numerous other languages, although the actual preserve may have been produced from fruits other than quince. The form of preserves made in the late Middle Ages gained the name marmalade and the recipe went through a critical change. Initially, quince was boiled in honey. As sugar production expanded in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries with the Portuguese in Madeira and the Azores, and later in the Americas, the quince and other fruit would be boiled in sugar.

In the sixteenth century, it is believed the Moors of North Africa taught the Portuguese to appreciate marmalade, so it appears that Arab food customs and recipes were the original source of Portuguese marmalade. Following the arrival of quince preserves in England, it was not long before English travelers to the Mediterranean brought back recipes, with English cooks creating marmalade from home-grown quinces and imported sugar. During the reign of King Henry VIII, marmalade was considered a highly prized gift.

Numerous cookbooks, from the years of Queen Elizabeth I going forward, contain recipes for cooking marmalade, indicating it had reached the masses and was considered a popular dish. Marmalades and other jellies, often perfumed and decorated with gold leaf, became one of the best loved sweetmeats of the Elizabethan banquet. Historical evidence exists showing marmalades were consumed by the English during the Tudor and Stuart eras for therapeutic reasons, with recipes appearing in household books and dispensatories at the time.

In addition to quince pastes, various confections and jellies prepared using other fruits would become known as marmalades. By the seventeenth century, marmalade came in various flavors such as grape, redcurrant, plum, citron, cherry and apricot. Samuel Pepys mentions marmalade in his diary. In the entries dated November 2 and 4, 1663, he writes that his wife Elizabeth is cooking the preserve. Although Queen Catherine may have eaten marmalade and it became widespread as a dish at court, marmalade was already in England. We can, however, infer that it arrived via Portuguese trade.

To find out more about Catherine of Braganza’s story, read Charles II’s Portuguese Queen: The Legacy of Catherine of Braganza, now available from your favorite bookseller.

Susan’s passion for history dates back fifty years and led her to study for a Bachelor of Arts degree in history at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She is currently a member of several historical and writer’s associations and her work has appeared on numerous historical websites and in magazines and includes guest appearances on historical podcasts. Her blog, The Freelance History Writer, has continuously published over five hundred historical articles since 2012, with an emphasis on European, Tudor, Medieval, Renaissance, Early Modern and women’s history. She is currently working on her third non-fiction book.