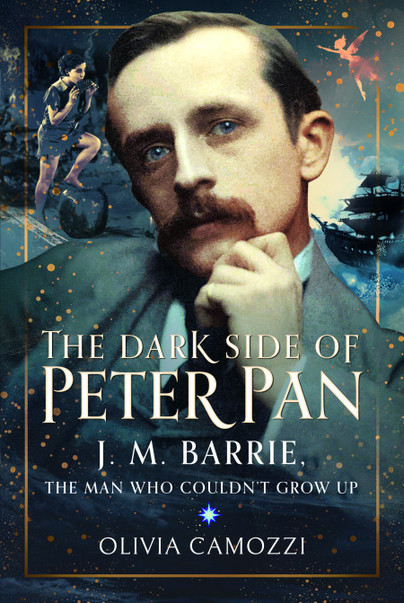

A modern perspective on J.M. Barrie: not the predator he’s been thought to be

Take a look at our guest post from Olivia Camozzi for ‘Peter Pan Day’

‘I don’t want ever to be a man’, wrote author James Matthew Barrie in Peter Pan, his most successful publication.

In recent years, J.M. Barrie has been reported as manipulative, perverted and even the stealer of another couple’s children, which are fair suspicions to have at first glance. However, just scratching the surface of this man will uncover complexities and traits that would be supported by modern-day communities.

It is predominantly due to his adoption of five boys after their parents’ deaths in the early 1900s that J.M. Barrie has come under scrutiny, as many look back on this and wonder what his underlying intentions were, when really there weren’t any, It’s been my intention to prove that Barrie wasn’t ‘incapable of love’ or a paedophile, but asexual and a victim of ‘Peter Pan Syndrome’ – a term only coined because of Barrie’s own work.

In fact, the life of J.M. Barrie was quite a long and sad one, with only brief bursts of joy and fulfilment.

Born in Angus, Scotland in 1860, Barrie experienced a charming and humble childhood with loving parents and several siblings. After leaving his hometown for Dumfries Academy, he made it clear in his personal notebooks that he was reluctant to leave childhood, which was tainted by the sudden loss of his older brother, David.

David was on that fine line between childhood and adolescence when he was killed in an ice-skating accident in 1867, on the eve of his fourteenth birthday. Barrie was just six, and later wrote of the tragedy, ‘When I became a man… he was still a boy of thirteen…’ This thought may be where Peter Pan’s character first sparked.

Experiencing this loss at such a young age was only the beginning of the grief that Barrie would become familiar with as he lost numerous friends and family over the years, but it was this first loss that may have caused him to cling to his childhood when so much of it had been overshadowed by a significant death. He missed playing pretend in the woods with his friends when they all began to take interest in cricket and girls instead, and the teenage Barrie didn’t understand why he himself didn’t get the same excitement around the opposite sex. Based on the notes in his personal notebooks, there’s no record of an attraction to boys, either.

After graduating from the University of Edinburgh with a degree in Literature in 1882, Barrie moved to London to pursue work in the theatre. Through the plays that he wrote, the author and playwright met numerous actresses that he appeared to take interest in, though his flirtations with these women only ever went so far; it was as if he enjoyed the thrill of the chase but grew bored as a child might do with a game. It was only after building up his name and meeting actress Mary Ansell that he started to feel pressure from the newspapers to take things further. He proposed to Mary, despite writing in his personal notebooks that their love bought him only misery, and they married in 1894.

Although only rumoured, some sources say that the marriage was never consummated, and there’s no evidence of Barrie showing attraction to anyone – men or women – outside of the marriage. He didn’t seem to feel any kind of sexual attraction to anyone, which in modern terminology we know as being asexual. In the Victorian and Edwardian era, this wasn’t yet a coined term let alone understood by the main body of society, so Barrie felt like an outcast even when he started to become mainstream.

Almost as if to distract his new wife from the lack of physical contact, Barrie bought her a puppy to mother on one of their trips abroad and purchased a holiday cottage for her to redecorate and furnish. They travelled, attended parties and kept busy as Barrie’s writing expanded from writing plays to publishing novels.

This isn’t to say that Barrie was incapable of love whatsoever, as he loved very deeply in other ways: platonically and paternally. Even after his divorce from Mary in 1909, he continued to support her financially until his death.

In 1897, Barrie met the Llewelyn Davies family. While walking his dog through Kensington Gardens he became acquainted with George and Jack, the two eldest children, who were five and four years old at the time. Peter Llewelyn Davies remained in his pram at the time the games started.

Barrie told the boys stories about fairies and magical children and relived the joys of his own childhood for hours with made-up games, eventually going on to meet their parents at a party. ‘Uncle Jim’ became a close family friend.

He began inviting them over to his holiday cottage to spend summer holidays and even took the mother of the family, Sylvia Llewelyn Davies, on trips abroad with one or two of the boys. Barrie’s wife and Sylvia’s husband made no negative comments about this, and no kind of affair was ever considered; Barrie loved and admired Sylvia as a mother, and it was this platonic love that sealed his devotion to the family.

When the fourth Llewelyn Davies child was born, Barrie treated the occasion as if it were his own son, showing that he did have a great paternal instinct; Michael was the first of the boys to know him from birth and became the author’s clear favourite of the bunch.

Although flawed with favouritism between them, Barrie’s love for the five Llewelyn Davies boys blossomed from a longing for fatherhood despite not being able to take the steps to become one. In a time when male-on-male affection was strictly frowned upon, he found his love towards them to be greatly suppressed as they grew older, and he couldn’t show much affection without others thinking it strange.

In one letter to George, he wrote: ‘What you don’t know in the least is the help you have been to me and become more and far more as these years have passed. There is nothing I would not confide in you or trust to you.’

This can be interpreted as very intense, but this was Barrie’s suppressed love bursting through him; many viewed Barrie as a quiet and brooding man because he was subdued around strangers, but his connections with those he loved ran deeply.

The best he could do was support the family when Arthur, the father of the boys, became unwell from a tumour and died in 1907. Barrie gave financial aid and offered unlimited time to Sylvia, cancelling or postponing all projects he was supposed to be working on. Sadly, Sylvia also died shortly after in 1910. Barrie adopted all five of the boys and spared no expense to their educations and general needs; all attended Eton College and university, and continued to experience holidays abroad.

But tragedy continued when George, the eldest of the boys, was killed in the First World War. Barrie was devastated and clung to Michael as a result.

In 1921, Michael also died in a suspected suicide. Barrie wrote later to one of Michael’s tutors, ‘…what happened was in a way the end of me…’.

The youngest of the boys, Nico, wrote of seeing his Uncle Jim just after receiving the news, as Barrie cried for Nico to be taken away: ‘Strangely, I don’t remember feeling hurt by this, rather did I understand in some way how my very closeness to Michael made his more or less uncontrollable grief even more uncontrollable…’

By the time of his death in 1937, J.M. Barrie had donated the rights of Peter Pan to Great Ormond Street Hospital. In an interview for a featurette covering the production of Peter Pan (2003), Nico’s daughter, Laura, was asked why Barrie had donated the rights to his most loved story. She replied: ‘I think he thought it would be a wonderful thing to do… children [had] always meant a lot to him… he related to children much better than he did to grown-ups. Always.’

So, was Barrie really a predator incapable of love? No, he was just a boy whose body grew around him. Perhaps in the modern day he would’ve found his community and felt more accepted, and his life may not have been so full of loneliness and loss. As Peter Llewelyn Davies wrote of him before his own suicide in the 1960s, ‘Oh, miserable Jimmie. Famous, rich, loved by a vast public, but at what a frightful private cost.’

Peter Pan made its stage debut in 1904 and was published as a novel in 1911. With a story that’s been loved by children and adults alike for over 100 years, the original text is often overlooked when navigating through numerous movie adaptations, pantomimes and plays, but much of the author’s character can be understood when analysing the text alone.

Order your copy here.