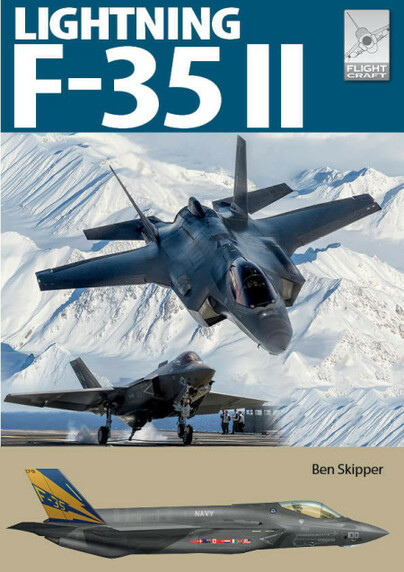

Lockheed Martin F-35; A complex solution to an easy question?

Author guest post from Ben Skipper.

Lockheed Martins’ second Fifth Generation aircraft, the F-35, will perhaps go down in history as military aviation’s answer to the M2 Bradley. Over price, overly complex and overly managed, the F-35 has almost become the byword for poor procurement in the popular press and in aviation circles. However, this reputation is poorly deserved. The F-35’s genesis can be traced back to the mid-1980’s when technical developments in aviation seemed to come thick and fast. This golden period echoed the enthusiasm that had come with the arrival of the Turbo-jet engine in the late 1940’s, but now the goal was the embracing of stealth characteristics and the utilisation of State-of-the -Art avionics fed by Silicon Valley’s microchip revolution.

At Vought, Lockheed, General Dynamics, McDonnell Douglas and British Aerospace, innovation continued to be fed by Cold War dollars and the need to be one step ahead of the Soviets. The Fourth-Generation aircraft available to NATO and allied partners, were increasingly complex, but remained based on those that went before them. Multi-role aircraft were increasingly common as the older Second and Third Generations space-age looking interceptors began to show their age and their restrictions of use. Aircraft such as English Electrics rocket-like Lightning and the famed McDonnell F-4 Phantom II, were increasingly left in the shadows by the likes of the new General Dynamics F-16 and the Panavia Tornado. These new aircraft captured the imagination of a generation of young people. The step from Strut-and-Wire to Fly-by-Wire was complete and everyone wanted a piece of the action.

In the late 1980’s two key events happened that would shake military aviation in particular. The first was the end of the Cold War, and with it the blank cheques from government to support aviation Research and Development, and the advent of Generation 4.5 aircraft that incorporated the latest developments in aviation engineering. Eurofighters Typhoon and Dassault’s Rafale are perhaps two of the most famous aircraft to come out of this sub-branch of development. Despite such developments there was still a need to replace older Third and Fourth Generation aircraft such as the British Aerospace Harrier, General Dynamics F-16 and McDonnel’s F-18. Indeed, plans for their replacements can be traced back to the early 1980’s, and this is where the F-35’s story starts.

The F-35 was always going to be a compromise in terms of design and capabilities, both shaped by available contemporary engineering restrictions and service-user requirements. There was also the extra task for partners to convince national Treasury departments that any investment in a new aircraft was worthwhile at a time when governments were enjoying the post-Cold War Peace-Dividend.

The F-35 was far from a ground-up project, it drew together several other projects giving the key partners a head-start on a design that would suit the needs of land and carrier-based users. As with any project of such a broad scope there was going to be compromise and complexity was going to be encountered. While the temptation to draw certain parallels with the development of the F-22, the F-35 is very much a different aeroplane, well three to be precise. There-in lay the source of many future research and development issues.

The F-35 was to be everything to everyone. It was to be a conventional, short take-off vertical landing (STOVL) and catapult launched multi-role stealth aircraft with centralised systems, some remaining under control of Lockheed Martin, and many highly complex. As a result of the main requirements, three separate aircraft were designed, with a fourth later exclusively designed to meet Israeli specifications and needs. Understandably costs rose, development was delayed and the F-35 and its early competitor the Boeing X-32, became testbeds for a host of new technologies. From the Diverterless Supersonic Inlet (DSI) to the unique Distributed Aperture System (DAS), that, like many military innovations, has found its way into the automotive industry, the F-35’s development was going to be both technically interesting and politically long.

As well as presenting engineers with Advanced Solution Opportunities, otherwise known as “problems”, the F-35 brought about the reimagining of vertical take-off. Here Rolls-Royce and Pratt & Whitney must be congratulated in creating a system that used cold, warm and hot air in a way that overcame Hot Gas Ingestion (HGI), a problematic feature encountered by STOVL aircraft. The end result was the unique Rolls-Royce Liftsystem, a development of an earlier Yakolev system, fitted to the main engine a PW F135 afterburning turbofan with adjustable nozzle, that would go on to win the 2010 Collier Trophy for “the greatest achievement in aeronautics or astronautics in America”. While this has certainly been good news for the Lockheed Martin, Rolls-Royce, Pratt & Whitney engineers, it delayed the overall project, added to cost overruns and arguably introduced an unnecessarily complex power source not suited to long-term field operations. On that latter point only time will tell.

As the F-35 entered service, the Lockheed Martin order books began to fill as nations outside the original funding partners were keen to add the F-35 to their flight lines. For the finance teams this was good news, but for suppliers, and Lockheed Martins dedicated assembly plant at Fort Worth in Texas, this presented further issues. Achieving a build rate of around 156 airframes a year by 2024, deliveries to customers have been slow, while continued service support, as a result of part prioritization, has been problematic, adding to varying serviceability levels.

That said the skies are clearing, and the F-35, one of the most advanced aircraft in the world, is slowly getting into its stride. To believe an aircraft of this nature would be an off-the-shelf option is to misunderstand its history, development and complexity. Yes, it has had its stumbles, but in recent years the F-35 has also shown it is capable of much more than the original briefs of the many 1980’s projects that led to its birth.

I sincerely hope that this Flight Craft title faithfully tells the story of the F-35’s development, the innovations that made it possible and praises the efforts of many talented individuals who have made the F-35 the aircraft it is today. I make no apologies for the M2 Bradley analogy I made at the beginning, but thankfully time has shown the M2 to be a very capable Infantry Fighting Vehicle, so its more than fair to say that the Lockheed Martin F-35 will undoubtedly follow suit.

Order your copy here.