The Government Code and Cypher School

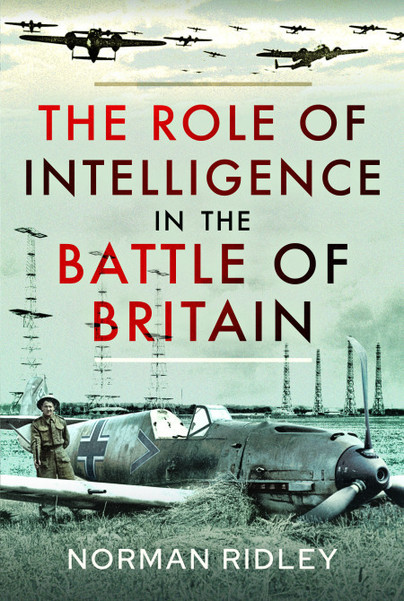

Author guest post from Norman Ridley.

The most obvious source of intelligence about Germany was the interception of enemy communications which was an old tradition, but which had changed in character with the advent of radio. The interception of electronic signals had continued, to some extent, since the First World War, but increasingly sophisticated encryption was a constant challenge to eavesdroppers. German expansion of its armed forces had, however, taken place with such speed that it had outstripped its ability to shield much of its communication network which meant that there was still a huge amount of radio traffic as opposed to transmission through fixed telephone wires.

This may not have been such a weakness had operators adhered strictly to time-consuming and tedious operational protocols but, especially in peacetime, there was little incentive to shield navigation signals, weather reports and low-grade tactical transmissions. This signals intelligence was acquired through the Y-Service (WI, Wireless Intercept) radio interceptor station at Cheadle which specialised in the interception of low-grade tactical communications using American HRO radio sets and made an important contribution to RAF Fighter Command operations.

The Y-Service was a network of listening posts initially set up all over the world to eavesdrop on radio traffic, but of crucial interest in the late 1930s were German radio communications. Y-Service personnel were highly skilled in languages and morse code and required particular qualities of concentration and precision. A special listening station was even set up inside Wormwood Scrubs prison to listen for radio transmissions that might be sent by enemy agents inside Britain.

Intelligence from Cheadle, however, was limited since German strategic decisions were rarely spelled out in wireless signals and the organisation for handling operational intelligence was defective in one important aspect. The Government Code and Cypher School (GC and CS) decrypts of high-grade German operational traffic was channelled into a different section of Air Intelligence from the low-grade Cheadle decrypts meaning that, due to the intransigence of Air Intelligence to sanction close cooperation between the two. different intelligence streams were never properly integrated until towards the end of the Battle of Britain, and even then intelligence was not shared in real time, only after the event.

In one important respect, however, both worked effectively towards an understanding of Luftwaffe organisation and order of battle. Cheadle had exploited the interception of the increasing volume of radio telephone communications by German-speaking WAAF and WRNS staff at Home Defence Units in small stations along the south-east coast, housed in caravans or clifftop cottages, produced important intelligence.

At the basis of all intelligence were the listeners. Without interception and recording of German signals there would no story to tell about Enigma or Bletchley Park. The listeners eavesdropped on both radio telephony (normal voice transmission) and wireless telephony (Morse code). Radiotelephony was used mostly by fighter pilots communicating with ground control or with each other in the air (they had been ordered to maintain radio silence during operations, but this directive was frequently ignored), so obviously the listeners were required to have a sound knowledge of the German language. Normally this traffic was on very high-frequency wavelengths (VHF) and could only be picked up in close proximity to the source. Luftwaffe bomber crews, however, used mostly medium and high frequency communications which could be picked up from much further away. This meant that listeners could often eavesdrop on bomber crew chatter as the larger raids formed up over Pas de Calais, often beyond radar detection range, giving vital extra minutes of warning. Wireless telephony signals were transmitted on high or medium frequency and often in code, but GC & CS had broken these codes. Listeners, mostly women, sat glued to earphones at intercept stations, working in shifts of six hours spent twiddling knobs and hectically taking down in pencil what they could.

It cannot be overstated what intelligence, skill and concentration was necessary for the listeners to become proficient at recognising individual German operators, sometimes by their accents in the case of radio or, in the case of wireless, by their individual styles of tapping out Morse code (their ‘fists’) which helped to identify the units, especially since unit call signs were frequently changed. This required a sensibility and delicacy of hearing that could only be gained by long experience. It was even the case that individual transmitters emitted a unique background noise that immediately identified them. Tuned in to given wavelengths with receivers orientated in a particular direction, listeners would wait in silence until a message would suddenly erupt in their earphones and they would have to respond immediately to capture the first crucial letters and transcribe each subsequent letter with unerring accuracy in order for the analysts to make sense of the message. All of this was of critical importance, given that when a signal in Morse code was first intercepted there was really no way of telling where it had originated. It was simply a sequence of sounds. What was known was the frequency of transmission, the volume of traffic on that frequency and possibly a clue as to the direction from which it had emanated. If a message was picked up from the beginning it would also usually include a call sign. Identifying the unit involved and its operating altitude often gave clues about the type of aircraft and the intended target. All this fed into the Filter Room at Bentley Priory and added detail to the overall picture.

From this meagre intelligence, even when the signals remained undeciphered, it might be, over time, found that a certain unit at a certain location with a certain call sign was often in contact with another unit (or units) at another known location with a known call sign, and from the accumulation of such intelligence could be derived a growing understanding of the German order of battle and sometimes, simply by virtue of a sudden increase in volume of signals, forewarning of a major operation such as the movement of a unit from one location to another, or even a major offensive. Knowledge of call signs was of paramount importance to breaking the codes. Fortunately, the British had two German code books, one captured in North Africa and the other captured by the Soviets and passed on to British Intelligence.

The reliance on medium frequency communications throughout the Luftwaffe bomber force allowed Cheadle to predict, with increasing frequency and certainty, the position, course, height and target of bombers and which units were involved. Even before aircraft had appeared on radar screens listeners were sometimes able to detect bomber groups forming up in preparation for an attack and even pass on information, based on voice intercepts, of the composition of the formations in terms of fighter or bomber aircraft. In some cases, signals could be picked up as much as thirty minutes before aircraft had actually left the ground.

This exploitation of Luftwaffe low-grade traffic was a serious weakness indicating either a level of desperation on the part of the Luftwaffe, or sense of material superiority over waning British resistance since the Germans would have been quite certain that their traffic was being intercepted, yet felt that the advantages for themselves in using radio so profligately in this very insecure way overrode any advantage it might have given to Fighter Command. Luftwaffe units such as KG 100, known to be pathfinders for the bombers, made free use of wireless in flight, meaning that targets were sometimes identified ahead of the strike – but wireless was intercepted by GC and CS, not Cheadle, and GC and CS intelligence was channelled into the long-term research section meaning that little, if any, of this intelligence ever found its way to Fighter Command in time for them to use it.

Order your copy here.