Author Guest Post: Nigel Walpole

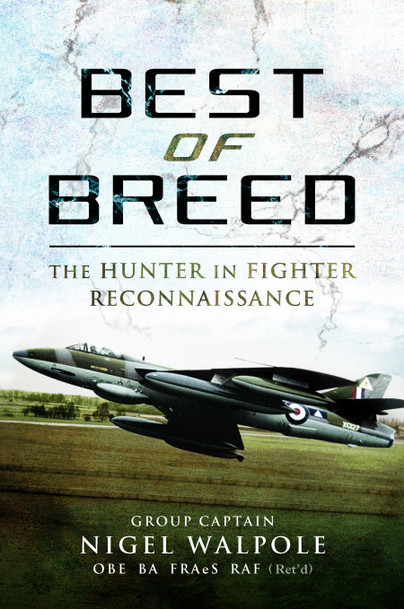

AIRBORNE WITH THE ‘BEST OF BREED’

An eerie silence seemed to have descended over the North German Plain, on that crystal clear Christmas morning of 1955, as we patrolled the Inner German Border (IGB) at 50,000 ft in our brand new Hunter Mk 4s, our guns loaded, looking for any suspicious activity in the air above the forbidden land of East Germany. Other than the gentle purring of our jet engines, and sporadic checks on our radios to keep us alert, our world seemed to be at peace – but this was the Cold War.

A year before, I had learned to fly the basic Hunter Mk 1, very alike our Mk 4s except that we had a little more fuel internally; both had early 100 Series Avon engines which tended to surge and flame-out, particularly at height if not handled with great care. We were also aware that the engine didn’t like us firing our guns, or ingesting the ammunition links if we did, but both these problems were resolved during the Hunter’s service in RAF Germany.

The evolution of the Hunter was little short of remarkable, being rapid and effective, culminating for the RAF in the fighter/ground-attack FGA9 and the fighter reconnaissance FR10 and all within six years of that Christmas Day, and I was fortunate to have flown all the RAF’s Avon powered variants.

The much heavier Hunter FR10 may have had difficulty at 50,000 ft, when carrying 2 x 100 gall and 2 x 230 gall fuel tanks on its wing pylons, but it was meant primarily for low level operations, with a more powerful 200 Series Avon engine enabling speeds of 600 knots. While not equipped to carry rockets or bombs, it had three excellent F95 cameras, mounted obliquely in the nose, retained its four 30 mm Aden cannon and its cockpit ergonomics were optimised for ultra low level, high speed flight; it was made for armed reconnaissance.

In the mid 1960s, the diverse capabilities of the FR10 were put to the test in the war against dissident tribesmen and rebel forces, backed by the Yemen and Egypt, in the Radfan district of the Western Aden Protectorate. The pilots on No 1417 (FR10) Flight, based at RAF Khormaksar in Ade, were specially selected for the many challenges there, of flying and map reading at 50 ft above the flat deserts, precipitous mountains and winding wadies, of air-to-ground gunnery and operating alone at maximum ranges. They had to find, plot and photograph camouflaged targets, perhaps mark them with their guns for action by collocated Hunter FGA9s, to use their guns to support ground forces and to render in-flight visual reports. Their immediate support was decisive in several ground operations, typically rescuing paratroopers from an ambush, and they were ready and able to engage in combat against MiG fighter-bombers, flown by Egyptians. This was serious stuff.

Also very serious was their part in NATO’s ‘deterrence’, with the two FR10 squadrons in Germany visibly able to contribute effectively to any war in Europe, they earned an enviable reputation in exercises for their rapid reaction, provision of near real time intelligence, and with an offensive and defensive capability. The Hunter FR10 was indeed ‘the best of breed’.

Preorder a copy of Best of Breed here.