Fighting with Pride: Lieutenant Commander Craig Jones MBE Part 2

We hope you enjoying our Fighting with Pride blog series. Today we have the second part of Craig Jones chapter, The Unsinkable. The concluding part of the chapter will be added tomorrow.

Fighting with Pride is out now.

My appointment in HMS Cornwall had been a great success and my skills at ship driving and leading had been carefully noted in my annual reports. In consequence there was a range of roles on offer, but the one that caught my eye was Executive Officer of a Northern Ireland patrol boat. I had thrived in the operational environment of the Gulf and had military skills in boarding operations and weapon craft that were seldom achieved by young officers employed in warships. Northern Ireland was experiencing a bloody period in its history and I relished the opportunity to be involved in an operational environment where I could add value. It seemed the perfect fit and I gladly accepted an appointment to HMS Itchen.

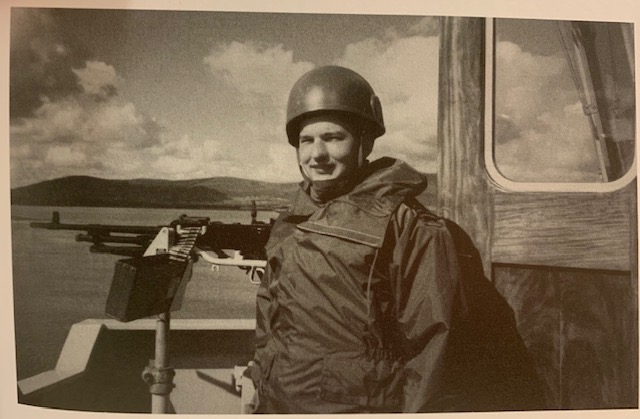

Itchen was a River class minesweeper that had been substantially modified to take a Royal Marines boat group. In preparation, I undertook more weapons and comprehensive threat training, to improve my awareness of the mortars being used by the IRA. There were also grave concerns about the use of sniper rifles in the border areas and the Royal Navy were considered significantly at threat. Itchen was a command platform for Operation Interknit, which was the patrol of the eastern border on Carlingford Lough and Operation Grenada, which was the patrol north from Carlingford around the coastline to Lough Foyle and Londonderry. Teams of Royal Marines from HMS Itchen and her sister ships boarded ferries from Warren Point and Belfast bound for the UK to check for known personalities, bombs, guns and contraband. We also mounted amphibious vehicle checkpoints, using the boat group to mount the beaches and move onto the road. Army units on the roads were carefully monitored and ‘dicked’ (reported on) by both the Republican and Protestant terrorists, and these operations mounted from the sea often caught sympathisers off guard. There was also the opportunity to board fishing vessels along the coastline in the hope that we might be passed some intelligence – and if we didn’t get intelligence from the fishermen, a lobster or a bit of halibut was always welcome. My greatest challenge was potcheen and sloe gin, used by many of the fishermen to stave off the cold winter in the Irish Sea. Alcohol and guns are a poor mix, but I always felt ungrateful at not sharing a dram with the fishermen on my patch. Whatever their faith or politics, most of those I met simply wanted to continue their lives without the chaos of this pointless and increasingly bloody war.

My team for boarding operations depended on the size of the vessel. For a small fisherman, the Royal Marines would drop off our military policeman and me, and possibly a sniffer dog if we had one embarked. Our military policeman was Regulating Petty Officer Tatcher. We got on very well, but like so many of his fellow rozzers, he didn’t have a strong understanding of the need for discretion, and in the presence of a crime, was like a dog with a bone. He was also a stickler for rules, something that made me nervous in front-line operations. There were times when initiative was needed, rather than rigidity. Tatcher tended to board fishing boats and pleasure craft with me. If there was a larger vessel or a ferry, we would send two bricks of Royal Marines (2 x 4) plus me and a bodyguard. In Northern Ireland there was a greater necessity to my having a bodyguard, because the most belligerent of locals knew what an officer’s beret badge looked like. That made me the target of quite a few punches and I was always pleased when my Royal Marine got a block in the middle.

I settled into the routine very well and in my first year worked longer days than at any time in my career. It was a tough time in Northern Ireland, during which there were many civilian and military deaths that gave our teams an acute sense of the importance of their work. We spent much of our time guarding the border on Carlingford Lough, but would occasionally trip up the coast to Kilkeel or Bangor for a change of scene and the possibility of some fresh fish. Once every couple of months, I disembarked the ship for forty-eight hours for intelligence briefings in Belfast with the RUC, Army Intelligence officers and some unshaven but clearly military individuals whose background was never discussed, but over the years it became clear that they were members of the Special Reconnaissance Unit, or 14th Intelligence Unit, as it was also known. These highly skilled and courageous undercover operatives provided background intelligence for Special Forces operations in Northern Ireland. Out and about daily on our ‘beat’, Tatcher and I were well positioned to provide information about the movements of people in the border regions, but in consequence, our faces were well known and we were at higher risk of a targeted attack.

In December 1993, our sister ship, HMS Cygnet, had come under fire from an IRA sniper using a 0.5 inch Barrett lite sniper rifle. This deadly long-range weapon discharged the bullet with huge kinetic energy and it could pass straight through the flak jackets in use at the time. It caused many deaths in Northern Ireland during my time there and was a silent and stealthy killer. The crew of Cygnet had dodged the bullet because the IRA had misjudged the range of the vessel and the bullets fell short.

We took as much care with our personal security as we sensibly could, never travelling in uniform without a 9mm pistol in a holster, or strapped to our chest when in civilian clothing. Although a flagrant breach of the rules, my pistol was permanently loaded and hung on my cabin door, ready to go. By the book, it should have been loaded and unloaded for each operation, but sometimes we got little notice of where the bad boys were on our beat, and every second counted. We were often exhausted, and each load and unload while mentally and physically shattered increased the chances of accidentally putting a round in the chamber – an almost daily event somewhere in Northern Ireland.

Getting me to Belfast for my monthly briefings was an uncomfortable and dangerous process called a ‘green move’. Our Royal Marine troop mounted the beach in the rigid raiders in a prearranged position on the northern coastline of Carlingford Lough, where we would meet three Snatch Land Rovers loaded with heavily armed soldiers. With the Royal Marines on the beach and the soldiers in the Snatch vehicles ready to provide covering fire, I would then walk across the no man’s land of the beach to meet them. Although only 100 yards, those walks were some of the longest of my life.

Entering Carlingford Lough, 1994, weighed down by body armour!

In November 1994, I completed my last green move of the year and arrived in Belfast at the Intelligence Centre for briefings. It had been a grim few months and the discussions that would eventually lead to the Good Friday Agreement had brought more instability than peace. The briefing painted a picture of very high levels of volatility and indiscipline in both Protestant and Republican paramilitary organisations, and it seemed that we were now increasingly at risk from both sides of this bloody war. In the margins of the briefings, there was a chance to talk to my family and restock on little luxuries to take back to Itchen. I was conscious that this would be my last chance before Christmas to do some shopping, so I put on some civilian clothing, strapped a 9mm pistol onto my right shoulder and donned my Harris Tweed jacket. I tended to wear a jacket rather than a coat because it would be easier to draw the weapon if needed. I’d booked a car to drop me off and collect me an hour later. I was rarely on the streets in civilian clothing in Belfast and whenever possible, I left my errands until my return to the mainland. Although we took great care to avoid advance planning of trips into the city, there was always the chance of a vehicle or driver or me being recognised, and the IRA had proven remarkably proficient at responding to opportunity targets. The driver dropped me on the high street, outside Dunnes department store, and I quickly left the car and slipped through the door into the crowd. The store was already showing signs of preparations for Christmas and as I walked through the cosmetics section, there were piles of box sets. Dressed in my jacket I was a target for the loitering assistants with their tester bottles. I walked purposefully and grabbed the lift up to the first floor in search of a new shirt. It was while meandering through the menswear section that I first noticed that I was being monitored. He was tall, perhaps over 6ft and wearing a denim jacket, checked shirt and jeans. I avoided looking directly at him but glanced as nonchalantly as I could to see if it was possible that he might have a weapon. He was clearly watching my every move and didn’t seem to care that I might have noticed. I made mental notes so I could describe him later to the Intelligence team. He was young, perhaps no more than 20, of athletic build. He had one earring, and it was forefront in my mind from the morning’s briefing that there were fresh faces in the ranks of the IRA and loyalist paramilitaries as the most belligerent dissidents looked for a new generation of operatives to replace an old guard that had lost much of its appetite for the armed struggle. I continued to observe him carefully, moving behind a Christmas display and towards the tills to see if he followed me, which he did, getting closer and closer. I scanned the shop for accomplices but could not see anybody else with whom he might be working, and the first floor of a department store seemed an unlikely place for him to move in. Then he looked straight at me and walked towards me. I lightly held the corner of my jacket to locate my pistol and make sure it was not visible, when he walked right up to me and said, ‘So what are you doing then?’ in a soft brogue. ‘I’m Army,’ I growled. ‘I know,’ he said with a cheeky smile. ‘That’s what all the cute hot Army officers wear.’ I recoiled in shock: this was not the risk I was expecting and I was dumbstruck. The best I could offer was a stuttered ‘What?’ Many soldiers had fallen foul of ‘honey pot’ abductions, but I’d never heard of a gay version of that. Could it be possible? Either way, it was a bad idea to stick around and find out. I had to get away. I pushed past him and hastily went down the stairs onto the street. As I neared the steps to the ground floor, I heard an exaggerated ‘Excuse me’ – but I didn’t look back. I dashed along the high street and found a café from which I could see my pickup place and waited an agonising twenty minutes until the blue MG metro arrived with my driver. I got in quickly and he drove off. ‘No shopping then, Sir?’ ‘No, nothing that I really fancied,’ I lied.

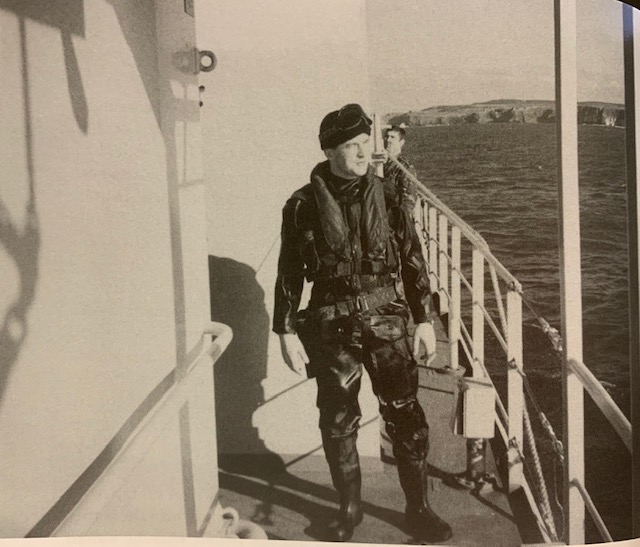

In the first few months of 1994, we received a closely guarded classified message to inform us that the Chief of the Defence Staff, General Sir Peter Inge, would visit the ship on Carlingford Lough. The plan was to winch him down using a Wessex aircraft. This was all achievable, but not something we practised day to day, particularly with an officer well into his sixties, so it needed some preparation. The General would tour the ship and have lunch in the wardroom. I spoke to our leading cook and he suggested that the General might like a bit of lobster, so we weighed anchor and sailed north towards Bangor to make friends in the fishing community! Tatcher and I donned our black drysuits, grabbed our pistols and scoured the horizon for a potter. About 3 miles south of Bangor, we spotted a large two-deck potter and closed in for the kill. As we approached, it was apparent that there was nobody on deck. The boat had a Bangor registration plate and we were able to make checks on its ownership to a sufficient level of reassurance to form the view that the crew were down below having supper (hopefully not the lobster we hoped to grab for the General!). Tatcher and I approached the potter’s low decks and I jumped over, helping my fellow boarder make his leap. It was all too quiet. I unclipped the webbing strap keeping my gun in place and slipped my hand over the pistol grip. Keeping as much cover as possible, I stuck my head through the tight hatch to the accommodation deck below. To my shock, there he was, the boy from Dunnes, on a mattress in the arms of another young lad on the deck of the main cabin. They heard my feet on the ladder and were now hurriedly grabbing for their clothes. The boy from Dunnes looked at me in disbelief. In 1994, the age of consent in the UK was 21 and the younger of the two was certainly a few years short of that. My zealous military police colleague would have loved to get his policeman’s notebook out so he could retell this tale in the senior rates’ mess. I stood in the middle of the hatch blocking Tatcher’s view. ‘Everything all right down there?’ he said. ‘Yes,’ I replied, adding that the crew were just resting. I caught the eye of the guy from Dunnes and he raised a grateful eyebrow. When I stepped out of the hatch, Tatcher looked at me quizzically, so to distract him I instructed him to search the cockpit before they got there. The bloodhound in him was sated by the possibility of a find, and he quickly set to task, opening drawers and cupboards. Not more than a minute later, the two young men appeared in the cockpit, in a state of mild undress and with tousled hair. Before they could speak, I said they must have had a busy day’s fishing and been tired. With discernible relief, they nodded. Tatcher was every bit the detective and asked why they had no fish. The older of the two boys neatly replied that they were pulling the pots for repairs. It was unconvincing to me, but Tatcher seemed to let it go. We stayed a few minutes more and then left them to their day. Back on board the Itchen, Tatcher and I went to the wardroom to write our boarding reports for the day and behind the closed door he asked me directly if they were ‘shagging’. I lied and sniggered as casually as I could, but he seemed unconvinced. In my remaining months on board I formed a view that Tatcher knew I’d covered something up and there was an air of distrust. He was a good man, loyal to his service and true to the regulations he was there to uphold, but if I slipped up, he would do nothing less than his duty as he saw it.

The boarding incident bothered me for some weeks afterwards. I was pleased that the boys had slipped away on their boat, perhaps shaken but otherwise safe. But for me, I had churned up the water around a void in my life. The pace of operations in HMS Cornwall and then in HMS Itchen had left little time for anything other than work, but I was 25, and in the weeks that followed I came to accept that I was hiding from the life I was destined to lead and that taking no risk in life would lead to a lonely outcome. Those two young men seemed to have the courage to be themselves, which I could not have dreamed of at their age. Courage comes in many forms and despite my beret, body armour and pistol, I felt like a coward. For over three years, I had immersed myself in some of the most high intensity military operations of the 1990s, but was I running to where my help was needed or running away from matters I could not face? The question left me shamefaced and I resolved to find as much honesty as my complicated life would allow.

Tooled up and ready to go, Bangor.

After Christmas leave and a docking period, we sailed back into Belfast Lough for my last few months of my long tour of duty. There had been an unprecedented number of attacks early in the new year, and security was very tight. I had been due to go home to Yorkshire for my first weekend off in early February. However, I was instructed to vary my travel plans and I booked a flight to Exeter to visit Roly Woods, my old friend from HMS Cornwall. Roly lived in a large guesthouse, which he owned with his mother, Alice. They were assisted by a lodger called Peter, who was 24, tall and strikingly handsome. That night, after an evening out in Exeter at a bar that to me seemed extremely Bohemian, I had a little too much Dutch courage and ‘came out’ to Roly, and he confirmed that Peter was in fact a little more than a lodger! And so I started my first gay friendship. Now I really did have something to hide.

That night over dinner, Roly and Peter made it clear that they knew I was gay, but with as much reassurance as they could offer that nobody else would have spotted it. There was a lot to take in and I couldn’t help but feel an unnerving ground rush. The following morning, we stepped out into a new world and sauntered along the road to the Exeter Arts Centre coffee shop, which was popular with the ‘boys’ on a Saturday lunchtime. As I walked through the door, amidst an exited and jolly crowd of young men, I spotted Adam on the far side of the room in a denim shirt and white T-shirt; he had a look of the Footloose about him. He was tall, neither blond nor dark, and quite a few years younger than me. I was transfixed and knew instantly that my life was about to become a great deal more complicated. We went on our first holiday together two weeks later over Easter leave … and the rest is our history!

………………..

In the summer of 1995, I left Northern Ireland for a long period of well-earned leave and to prepare myself to be the navigator of the frigate HMS Sheffield. Adam, then 19, had gone back to college to improve his grades and we spent the summer learning simultaneous equations and quadratics! It was a wonderful time in my life and my smile beamed from ear to ear. HMS Sheffield was a fine ship with over 200 crew, and I was excited by the new appointment. I completed the Frigate Navigator’s Course in the autumn and joined straight after Christmas. My career was soaring, and I had found the missing part of my life and was walking on clouds. It would be a very long fall from grace.

In the second week of January, Adam’s father (who was separated from his mother) very suddenly dropped dead. It’s the type of turn of events that the military manage in their stride every day, affording servicemen and women compassionate leave to support them to resolve issues at home such that they can continue their service duties with necessary reassurance. That system was not available to me and as HMS Sheffield sailed from Plymouth, I felt as though I had abandoned the love of my life. Still in shock, Adam was suggesting taking a break from his studies. So early in his task of crafting a new pathway for his life, I was determined that that should not happen. The best way I can describe the twenty-four hours that followed would be to say that it was, for this young lieutenant, ‘all a bit much’. In frigates, navigators are in short supply. There were no others on board who could jump into the role for anything other than the short term; all other officers had their own roles. It was apparent that I was unfit to continue and a helicopter was swiftly raised to bring the Squadron Captain and a relief navigator on board and get me to hospital, where I remained for twenty-eight hours under sedation.

An hour’s discussion with a surgeon captain psychiatrist established that I was not suicidal and I was sent on long leave. In my hospital bed I’d spent my time making lists in my head of things I needed to do to resolve the challenges at home. I was far from suicidal; I was going to be busy sorting things out and getting back to work. Nevertheless, this was a time of great sadness. I had shot a torpedo into my career that would take years to patch up.

When matters at home had been resolved as best they could, Adam and I decided a holiday was needed. In February, sunshine and warmth is in short supply in the northern hemisphere so we boarded a plane to The Gambia. There was a bit of civil unrest going on there, but it wasn’t Belfast! On our second morning, I was sat at the bar reflecting on a chaotic period in life, when a man of a similar age, who I had seen with his boyfriend, sat on the stool next to me and said, ‘You look bloody miserable.’ In recent weeks I had come perilously close to losing a service career that mattered a great deal to me and exposure to the risk had curiously taken the edge off my nerves amidst my newly found gay bretheren. I flicked open my wallet on the bar, showed him my military ID card and said, ‘That’s because I’ve got one of those [pointing at the ID card] and one of those [pointing at Adam].’ Sergeant Darren Ford, Royal Military Police, flicked open his wallet and revealed his Military Police warrant card, then pointed at his boyfriend. I hadn’t considered that anybody else could be worse off ! With great sadness, I discovered eighteen months later that his boyfriend outed him to the Royal Military Police and Darren was required to resign. He was a remarkable police sergeant and the Army lost one of its best.

My penance for leaving HMS Sheffield was to be sent as the third navigator of an aircraft carrier (when in fact an aircraft carrier only has two navigators!). It was a made-up job, sharpening pencils on the bridge, but it was where my complicated life had led me and I was determined to be the best pencil sharpener in the Fleet, if that was what was needed. HMS Illustrious was commanded by Admiral Sir Jonathan Band, a good man with fondness for cigars and rugby. He was a charismatic and well-respected leader. Sadly, I would never be an officer he could fathom, but that was not entirely his fault. I suspect he was mystified at my departure from Sheffield and very keen that I should return to navigate a frigate or destroyer to ‘finish the job’. In my confidential report, Captain Band described me as ‘intense and private with a reserved personality and worried manner’. He also noted – as was the reporting tradition at the time – that I was single. Much as the report burned in my mind like a fire, it was the man I had become – it was the damage done. Little more than twelve months earlier, my final confidential report on leaving Northern Ireland had described me having ‘personal qualities beyond reproach, honest, loyal and courageous’. It continued that I was ‘confident in all I did, a generous, charming host with a sharp wit’, recommending me for early promotion and to command a small ship.

There were no questions that Captain Band could have been asked that would have helped me or I could have answered honestly. I faced this alone. Perhaps more than anything, this painful epoch laid the foundation of my bold and challenging reaction to the poor treatment of LGBTQ servicemen and women from the moment I could stand our corner. They had suffered enough.

And then the turn of fate rounded the right corner. As part of my penance I was from time to time given additional tasking. One of these tasks was to organise the visit of Captain Roy Clare CBE, who was to be the new commanding officer of our sister ship, HMS Invincible. It wasn’t a task I relished, but it needed to be done, and done well. I rolled up my sleeves and got on with it, meeting Captain Clare on the gangway with a programme that filled every minute and ran like clockwork. He was briefed by our weapons and marine engineers, our aircrew, our bridge and operations room teams, and he had dinners and lunches in each of our messes and spent time with Captain Band. As I bid him farewell on the gangway at the end of his visit, he asked me what would be next in my career. It was a question that was difficult to answer and I stumbled on my words, finally managing to tell him that HMS Invincible needed a deputy navigator. He smiled, nodded and agreed to make some calls. A few weeks later, I walked across the dockyard for a new ship and a new start. I have no knowledge of what Captain Clare knew about my ‘difficult year’, but as I joined HMS Invincible, I remember feeling safe.

………………..

It was late 1997, and the furore of the debate about ‘gays in the military’ was a national news story that developed week by week. Admiral Sir Jock Slater, then First Sea Lord, printed an open letter in a national newspaper defending his position that the exclusion should continue. He was well supported by British Army and Royal Air Force service chiefs and the case seemed won for now. His successor as First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Nigel Essenhigh, was widely rumoured to have threatened to resign if the prohibition was lifted. One lunchtime, I was sat in the wardroom on board discussing the situation with a group of young lieutenants and I heard myself say that I simply hoped we would ‘never have to serve with those kinds’. Shortly afterwards, I left and went to my cabin. I slid the door closed and, not for the first time, sat at my desk with my head in my hands. It was a shocking moment of Judas and I was thoroughly ashamed of myself. I vowed it would never happen again; no matter what the risk, I would never deny who I was. An economy of the truth might be acceptable, but a lie was not. My first moment of being tested was to come very soon afterwards.

I got on with Captain Clare very well. He had a reputation for nurturing the careers of young officers and was an inspiring leader. Specifically, when he entertained senior officers in his dining cabin, he always shared the occasion with one or two more junior officers and I was delighted to have received an invitation card to a lunch where he would host the commodores of the main Royal Navy shore bases in Portsmouth (HMS Sultan, HMS Nelson, HMS Collingwood and HMS Excellent). The lunch was a jovial affair, bringing together a group of contemporaries who knew each other from many previous ships and roles. It went well and we worked our way through three courses of delicious food prepared in the Captain’s private galley. As the cheese and biscuits were served, the discussion turned to ‘gays in the military’. This was not altogether unusual; despite the unease of some, the most senior officers were generally keen to defend their position. At the lunch, the discussion was strong and loud and passionate. Captain Clare I thought would be the last to speak, and I doubted my opinion would have any importance; in fact, I expected to be overlooked. Captain Clare thought otherwise, and like a stray missile, the question came: ‘And so, Craig, what does a younger officer think of gay men and women serving?’ I had made my promise and carefully considered and accepted the risks. I understood my duty; there were no options for me. With a stony face and a seriousness and gravity that was to become a hallmark of my most difficult discussions, I reminded the commodores that they had spent fifteen minutes discussing slow progress in the procurement pipeline for new aircraft carriers to replace the ageing Invincible and Illustrious and well over half an hour discussing ‘gays in the military’. I continued that if the First Sea Lord devoted more of his precious time petitioning for new carriers and less time trying to stop gay men and women from serving (which they were doing anyway) then perhaps we might all do better. There was a stony silence and tangible discomfort. It was not the response expected. Admiral Clare threw me a life ring. ‘You’re quite right, Craig. We sound like dinosaurs and it will be good leadership to see the ban lifted.’

After the dinner I retired to my cabin, proud to have found my voice but feeling vulnerable from the experience. The next day, during ‘stand easy’ (morning coffee, in Navy parlance), the main broadcast sounded and I was called to the Captain’s cabin. I dashed up the ladders (there’s an anticipated expediency to such orders barked on the main broadcast). After knocking with appropriate firmness, I put my head around the curtain on his door. He beckoned me in and pointed to an editorial at the foot of The Times: the headline read ‘Writing on the Wall for Gay Ban’. ‘They seem to agree with us,’ retorted Admiral Clare. He handed me the paper and said, ‘Take it.’ (Because of the shortage of up-to-date newspapers at sea, there is a tradition of them being passed around.) I thanked him and left without further comment. After the ban was lifted I wrote to Admiral Clare to ask if he had seen beneath my cloak. With great warmth he remarked that he had not, but knew without a shadow of doubt that the continued exclusion of gay servicemen and women was wrong.

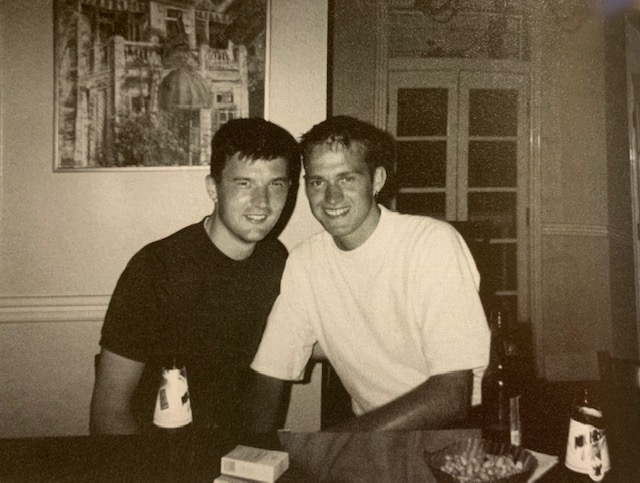

Adam and I escaping for our first holiday together – Key West, 1995. The world was suddenly in brilliant technicolour and I had never been happier. Whatever the future brought us, we would face it together.

Through the bleak years, I was constantly aware that it would be all too easy for Adam to take a view that my much beloved Royal Navy was in some way an unwelcoming organisation or indeed one that did not place great importance on the role of our families. The reality is that the service greatly values the support that our families offer. He needed to understand the service and as he went to Sussex University in 1997, I very strongly encouraged him to join the University Royal Naval Unit, reflecting back on my time in HMS Fencer. I coached him for his interview and polished his shoes the night before. By then he knew far more about the service than any ordinary student and within weeks, he had a midshipman’s uniform and an ID card. In a very positive environment he developed his own love for the service and experienced short summer and Easter deployments in his unit’s patrol boat. It was not an aircraft carrier, but it was grey and flew a white ensign, and that seemed to be enough. He learned to coil ropes, put lines of pencil on charts, and which way to pass the port and Madeira. It was a terrific experience until he came home one day after ‘drill night’ and told me his new commanding officer had joined. ‘Fantastic,’ I said, ‘what’s his name?’ ‘Matthew Reed’ was the answer. I hadn’t seen Matthew for a few years. Our deployments had taken us to different ships in different parts of the world, but I considered him a close friend and, like all my fellow officers, did not wish him to be burdened by keeping my secret. Adam and I agreed that we would carry on provided that I had no contact with Matthew. Then, one evening, Matthew called me from Brighton Marina to say that he was bringing his little ship in for the night and would love to come round for a ‘catch-up’. As I put the phone down, Adam and I looked around the room, our eyes falling on a Shirley Bassey tour poster – we needed to urgently ‘de-gay’ the flat. In a scene reminiscent of The Birdcage, we dashed around for an hour removing all traces of style, trying to create a ‘bachelor pad’. After his visit that evening, Adam resigned from URNU. He’d had a great time, but it was our problem and not a burden to be shared. Adam’s time in the URNU was to have been of great importance, though. When the time came, Adam walked across the brows of ships and into wardrooms and messes with a confidence, bearing and courage of conviction of a member of the Officer Corps.

My appointment to Invincible went well and Admiral Clare recommended me for staff training and the prestigious Principal Warfare Officer’s Course. The course was the foundation for becoming a senior officer in my branch and I was delighted. However, it would give me access to closely guarded military secrets and it was necessary that I be security cleared to routinely see information marked ‘Top Secret’ or that was so secret it had unique code words with access nominated individually by name and rank. Security clearance at that level made it likely that I would be exposed. For many years, Adam and I had shared bank accounts, mortgages and a home. Those ordinary connections of life were backed up by comprehensive records, to which military vetting officers had access.

And so, with mixed feelings, I bade farewell to Admiral Clare and walked down the gangway of HMS Invincible for the last time and moved on to the Military Staff College at Bracknell. If my career was to be curtailed by simple honesty, was it really all to be ended in Bracknell? It seemed an unlikely place for my last stand. And so the letter came in the post. I was to be interviewed by a retired colonel from the Defence Vetting Agency. It was May 1999, and my colleagues were thoroughly absorbed in the European Cup Finals and thankfully sufficiently distracted to not notice my personal disquiet as I counted the days to my interview and reminded myself that I would never again deny who I was. Although it was then less than 100 days from the European Court Ruling, my career would nevertheless end within twenty-four hours of disclosure. I met the Colonel in an interview room in a small military police unit at Bracknell. There were two chairs and a table. We shook hands. He was an older officer, dressed in tweeds, who looked at me over his half-moon glasses and invited me to sit down. Over the hour that followed, we discussed the things that concern vetting officers, focusing on the risks. We covered my life as a teenager, my family and friendship groups, gambling, drinking and prostitutes, as well as involvement with foreign nationals, places I’d been on holiday and some gentle questions about my current home life. But the questions seemed to lack the difficult probity I expected and we seemed close to the end of the interview … and then, it came. ‘Commander Jones [a compliment because I was in fact a lieutenant commander], I have listened to your very earnest questions about your life and reflecting upon your answers it seems most likely that you would not be the sort of officer who I would need to ask about their being involved with homosexuality. Is it correct that I need not ask you questions on that matter?’ Despite my expectations, it was a bolt from the blue and I quickly analysed the question I’d been asked. Thinking as quickly as I could, it seemed that the question was ‘Do I need to ask you about homosexuality?’ No, he didn’t – I was quite happy with my homosexuality! And so I replied, very simply, ‘No sir, you don’t.’ ‘Good,’ he said. ‘It’s been a pleasure meeting you.’ And he turned and left.

Years later, as a more senior officer, I realised that he knew. The vetting agency had unrestricted access to a wide range of documents as an enabler to their important work of making sure that defence secrets are safe. I had clearly been risk assessed ahead of the interview and deemed to have the integrity to be unbribable. On reflection, it was the beginnings of a change of heart at the MoD, but unable to see that, I simply breathed a puzzled sigh of relief and moved on with life.

And so, in the closing months of 1999, I was the perfect storm: a determined and gritty professional war fighter with an innate sense of justice who had watched ten years of denigration of duty and abandonment of the covenant by service chiefs. I had seen colleagues dismissed, outed and humiliated, and I had seen the careers of talented servicemen and women lost. By then my confidential reports were once again positive, but damage had been done and I knew what injustice felt like. The time was coming when I would never again have to stand by in silence, and there was a fire in my soul that would not be put out. That fire had been kindled in a battle; the battle for the covenant was not over and I planned it would be won.

I wasn’t always angry. At times, I was almost an apologist for an Armed Forces that, for a period of time, chose to set aside its core values. Before the ban was overturned and early in my career I almost convinced myself that it seemed reasonable that service chiefs might defend their long-held position. But as the years passed, good men and women were dismissed and the covenant was left behind. As I witnessed the damage being done, it became very clear that the day would come when I would draw my sword and charge, not in spite of my commission and duty, but because of it.

………………..

Fighting with Pride is available to order direct from Pen and Sword Books.