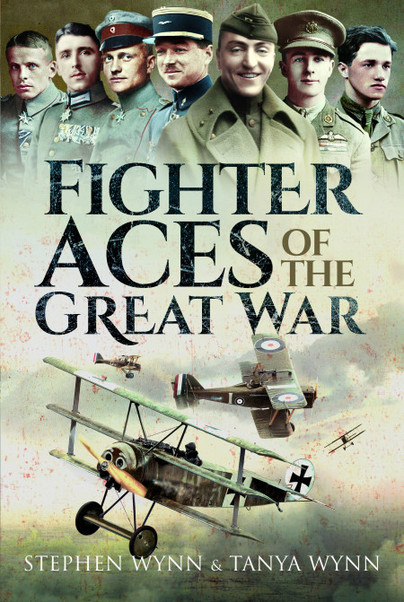

Guest Post: Stephen Wynn

The entire world changed with the beginning of the First World War, not just in a military sense but socially as well. Never again would the world ever quite be the same. Much had to do with the sacrifices that people and their families made during the following four years, because with this came an expectation of a better tomorrow.

What we know as the modern day aircraft was first invented by brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright. They made the breakthrough of a successful manned flight on 17 December 1903, covering a distance of 120 feet, which took 12 seconds. Eleven years later the First World War began.

A total of 22,000, British and Empire men completed and passed their training and went on to fly with either the Royal Flying Corps, the Royal Naval Air Service, or the Royal Air Force. Of these, somewhere in the region of one in five were killed either in combat or as a result of an accident. On top of this, more than one thousand trainee pilots died while undergoing training with either the Royal Flying Corps or the Royal Air Force.

In the initial stages of the war, the full capability of the aircraft had not been fully understood. Its main purpose at the beginning of the war was that of reconnaissance. This involved taking photographs of enemy trench systems. Artillery spotting, which allowed for the accurate targeting by British and Allied artillery gunners of enemy gun positions, and what was referred to as “contact patrol” where aircraft would follow the course of a battle and then drop messages to the advancing infantry units below.

These early aircraft had no machine guns, and if they came in to contact with each other in the skies, they could only engage each other by means of small arms or grenades, even when bombs were carried on board to drop on enemy position, this had to be done by hand. The first recorded case of an air engagement involving a synchronised, gun armed aircraft, took place on 1 July 1915, over Luneville in France, when a German pilot flying an Eindecker aircraft forced down a French Morane-Saulnier “Parasol” two seater observation monoplane. And that was the beginning of aircraft being used for offensive purposes in the First World War.

No matter what side pilots and air crew were on, they were all very brave individuals, with many of them still in their late teens or early twenty’s. By the end of the war Germany had lost 27,636 aircraft, France 52,640 and Britain 35,973. This meant that averaged out Britain lost 25 aircraft for every day of the war. Many of the aircraft were unpredictable and were made of nothing more substantial than a wooden frame with canvas stretched over.

In April 1917, two and a half years in to the war the average life expectancy of a British pilot on the Western Front was 69 flying hours, three hours less than three days. Would I have volunteered to be a pilot if I had been alive during the course of the First World War, no, not with what I know now. Remember British pilots were not allowed parachutes, even though they were available, the authorities claimed because they were too bulky, and might affect the performance of the aircraft, but the reality was that British authorities believed their presence on an aircraft “might impair the fighting spirit of pilots and cause them to abandon machines which might otherwise be capable of returning to base for repair.”

You can order a copy of Fighter Aces of the Great War here.