Sir Herbert Walker KCB

Guest post from author Peter Steer.

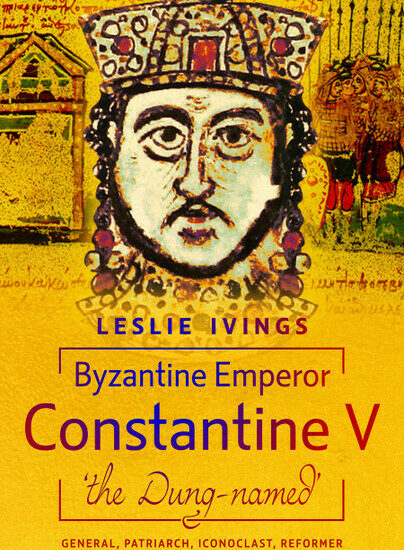

In 1973 Ian Allan published Charles Klapper’s biography of Sir Herbert Walker entitled ‘Sir Herbert Walker’s Southern Railway’. A good title because to many people Walker was the Southern Railway and as such his story was inextricably linked to that of the Southern Railway. So, when I wished to write a biography of Alfred Raworth, I used the same titular device and called my book ‘Alfred Raworth’s Electric Southern Railway’ since he was the electrical engineer for new works and had been at the very centre of the development of the railway’s expanding electrified railway network. All commentators and authors concur that Sir Herbert was the driving force behind the continuing development of the Southern Electric network, but he needed the specialists such as Raworth to realise his ambitions.

Walker is described in The Oxford Companion to Railway History edited by Jack Simmons and Gordan Biddle as being ‘…deeply impressive, with a remarkable grasp of all aspects of railway work; quiet yet authoritative, stimulating his subordinates to give their very best…’. During my research for my Raworth biography, I began to formulate a more nuanced view of Sir Herbert’s character. He was physically a big man, an imposing figure broad and tall. I am sure that when he spoke with his staff in the safe confines of his wood-panelled office at Waterloo station he did often appear ‘quiet’ and ‘authoritative’, but when engaged in upholding the Southern Railway’s interests with outside bodies he would often employ bluster and half-truths. For example, following correspondence concerning the fencing-off of the electrified lines, one civil servant having read what Walker had written was moved to describe his words as “…superficially plausible nonsense…” While it is difficult at such a distance in time, perhaps Walker’s reputation and management style should now be re-evaluated.

Herbert Walker was born in 1868 in Paddington. Herbert’s father was a doctor, and the original intention was that the young Walker was to follow in his father’s footsteps. However, what official sources have quoted as ‘family reasons’ (and here we must surely suspect a lack of finance), Herbert gave up his full-time medical studies to earn his living and took up employment with the London and North Western Railway (LNWR). He started his railway career at the age of seventeen as a clerk in the London Division offices of the LNWR but his rise through the ranks was to be meteoric for after several promotions in 1911 he appointed as the outdoor goods manager for the southern area of the LNWR. His abilities may well have been recognised by the LNWR but not fully rewarded. After years of experience across the LNWR system he was to represent the railway on several occasions including at many public inquiries when he was officially presented as an ‘assistant to the general manager.’ It was at such public inquiries that the London and South Western Railway (LSWR) chairman, Sir Hugh Drummond, took notice of Walker and when the LSWR general manager post became vacant he wrote directly to the LNWR’s ‘assistant to the general manager’ with the offer of the post of general manager of the LSWR. Herbert Walker duly accepted this belated recognition – even if it was from another railway.

During the Great War with the railways coming ‘under government control’ Walker led the Railway Executive Committee for which the chairman was, officially, the president of the board of trade. In practice it was his ‘deputy’, Herbert Walker who was elected by all the other railway general managers to chair the committee. For his war work he was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB) in 1917.

After the Grouping creating the Southern Railway, the new company at first continued to be run by three separate ‘territory’ boards replicating the main three constituent companies, the London and South Western Railway (LSWR), the London Brighton and South Coast Railway (LBSCR) and the South Eastern and Chatham Railway (SECR). My research into matters concerning which electrification system was to be the ‘standard’ for the unified railway have shown that, apart from Walker and Drummond, the directors and managers seemed to view the Grouping as being in name only, each of the three railways would continue much as before operated by a local board under the umbrella of a federal Southern Railway. In many aspects this conflict of views mirrored the current political situation. During the First World War the prime minister Lloyd George had run a tight organisation instigating full cooperation between government departments and private business who had worked collectively towards a common goal. Walker, at the Railway Executive had overseen what was in effect a ‘national’ system to pool resources and hopefully eliminate any duplicated effort. The Liberal Lloyd George who was promptly re-elected after the armistice, wished to continue with this cooperation in the wider national interest but faced opposition from those (mainly Conservative MPs) who wished to return to the pre-war environment of ‘competition’ and ‘freedom’ that advantaged those who had multiple directorships in companies whose aim was to benefit shareholders, not the nation as a whole. In this climate nationalisation was obviously considered to further Lloyd George’s vision, but one of prime minister’s cabinet, Sir Eric Geddes the first Minister of Transport, was not averse to a private rather than a state monopoly. The Grouping thus was a compromise, four independent private companies which were to be tightly regulated. This compromise did not go far enough for many directors and managers in the ‘Southern’ group hence the push for three separate ‘territory’ boards.

In January 1923, the newly created Southern Railway had only the central secretariat and stores department serving the three former railways. Walker may have been the youngest of the general managers from the three companies but, as the wartime leader of the Railway Executive, he was the obvious first choice to be the general manager of the new Southern Railway. It took Sir Herbert’s threat to resign and the strong will of Sir Hugh Drummond to force the issue to create a single Southern Railway structure. Among the many conflicts of interest between the constituent companies was the decision as to which of the three electrification systems should, or could, be the standard for the new railway. The LSWR, led by Walker, put up and aggressive (and successful) case for the adaptation of their third rail system. The LSWR’s argument was at times mendacious using many ‘half-truths’ to make their case. By ‘half-truth’ I mean that things were said that were strictly correct but misleading as they were presented out of context.

In an early message printed in the new company’s staff magazine Sir Herbert extolled the virtues of standardisation. He opined that the upheaval of the Grouping was pointless if not accompanied by standard working practices within a central management structure. Walker was successful in bringing together the various units from the three companies, but the very nature of the inherited network in certain respects tended to work against his ideal. The traffic patterns and location of the workshops and servicing depots built up by the three companies naturally led to lines of command very close to those in the pre-grouping era. By the late 1920s a further reorganisation divided the railway for traffic operating purposes into four divisions along the lines of the three companies with the LSWR territory being split in two as ‘London’ and ‘Western’. In a sense these matters have not changed today, thanks to privatisation trains on the SECR lines are operated by Southeastern, those on LBSCR lines are operated by the company that has usurped Walker’s railway’s name ‘Southern’ and ‘South Western Railway’ (not a ‘railway’ but a train operating company) which run the trains over those LSWR lines that have not been closed or, often further west, by the ‘GWR’.

Walker was deemed to have the ‘common touch’ in that he would freely converse and remember the names of even the lowliest of SR staff. He was from an age when each man had his ‘station in life’ and was to be respected for his contribution to society – however menial. Each employee brought a skill to the business and Walker respected this. Unlike today there was not the simplistic view that ‘anybody’ can do an apparently simple task – for this today often leads to ‘nobody’ being able to do the job. Walker showed loyalty and respect to the ‘railway family’ during the economically hard times in the early 1930s when the Southern Railway’s overall receipts were falling due to the Great Depression and to road competition. He reluctantly had to instigate an overall pay reduction of one and a quarter percent across all grades of employee (including himself) and this followed a two and a half percent reduction back in 1928. Bad that this was for the lowest paid workers it did demonstrate a caring attitude towards the staff as a management faced with such a situation today would drastically reduce staff numbers. Nonetheless Walker would not have enjoyed the full appreciation of the workforce. When the statutory eight-hour working day was introduced he considered its application as ‘insidious’ on the basis that a man working in a quiet west country signal box had an easier shift than a signalman in a hectic London area box. Walker seems to equate value with the amount of work done rather than the man’s time input.

A feature of Walker’s management style was to appoint trusted lieutenants to lead each department and to give them full scope to carry out their work with a minimum intervention. Given reports of friction between such men it is my opinion that possibly Walker operated a ‘divide and rule’ policy. This led to a situation where such ‘chiefs’ wielded an almost autocratic power over their departments. One such the Chief Engineer George Elson had complaints about bullying made against him from some of his senior staff. As reported in John King’s book ‘Gilbert Szlumper and Leo Amery of the Southern Railway’, Szlumper, then Walker’s assistant, decided to effectively sweep these allegations under the carpet – for the ‘good of the company’. There must however be the suspicion that Walker would not interfere with the running of Elson’s domain. This, based on what has been published, seems to be the end of the story, but I cannot believe that the all-knowing Walker did not get wind of the discontent. Had he found out about Elson’s bad behavior, the Chief Engineer would have been summoned to the General manager’s oak-paneled office at Waterloo to be given an almighty dressing down by Walker. The details of such an uncomfortable meeting would have remained confidential between the two men. This approach differed from one of his successors, Eustace Missenden, who would be more likely to berate senior managers at minuted officers’ conferences.

Walker was not loyal to his long-suffering assistant general manager. Note ‘assistant’, not ‘deputy’. Gilbert Szlumper had been the secretary to the Railway Executive Committee during the Great War and thus had no input into the committee’s decisions but had to carry out Walker’s instructions. Little seems to have changed to this master-servant relationship when in 1925 Gilbert was appointed as the assistant to Sir Herbert Walker. This was not a particularly happy time for Gilbert. He was in effect Walker’s ‘bag carrier’ there only to do his master’s bidding but given little direct responsibility. For example, when, strangely, Walker did not attend the opening celebrations for the inauguration of the Brighton electrification on the last day of 1932, Gilbert had to read out the speech prepared by his master. Another example of Szlumper not being ‘in the loop’ was when in October 1936 he only discovered by listening to office gossip that Walker was about to leave the country on a seven-week trip to South Africa. So frustrated did Gilbert become that he confidentiality relayed his concerns to senior directors telling them that he was seriously considering leaving the Southern Railway and attempted to get a promise from them that when – and if – Walker retired he would be appointed to the post of general manager. His concerns were two-fold: Walker was forever retiring ‘next year’ and there were rumours abound that post-Walker a less personality-centred organisation might be established with directors taking a more executive role. This arrangement would have been similar to the ‘presidential’ structure on the LMS with a layer of vice-presidents. It would seem that the directors were happy for Walker to be in full control (a ‘benevolent despot’ as one director called him), but they were not sure if the existing structure would be possible with a manager of lesser ability. The ‘presidential’ proposal was however discarded and Szlumper did become the general manager.

Walker enjoyed his leisure time in his London club and earned a reputation as a raconteur and after-dinner speaker. Probably it was his late-night tales that ‘improved’ with each telling, that are the source of some outrageous anecdotes such as recounted by Charles Klapper. The notion that an architect would design a substation building without an entrance door is ridiculous enough without Walker insisting that he with his electrical engineers, Jones and Raworth, having arrived on a site inspection visit had to take sledgehammers to break down a wall to free a party of bricklayers who had inadvertently bricked themselves in. This is a good image but surely fantasy. Similarly, the story that when the Seaford branch was electrified with immediate reports of the signalman receiving electric shocks from his levers etc., it is hard to believe that Walker was first on the scene and recommended dropping a copper conductor into the sea of Newhaven Pier to earth the system does not seem plausible.

Sir Herbert Walker was born a Victorian but matured as an Edwardian. By the 1920s and into the 1930s he seemed out of place in the contemporary world. Nonetheless with his solid values he held the Southern Railway together and approved modern technology to uphold the companies prosperity. Without him it is unlikely that the extensive Southern Electric electrified railway would have evolved, and he deserves credit too for expanding the facilities at Southampton and early ventures into air transport. His loyalty to the railway staff – in particular to his senior officers – was never in question. Following his retirement Sir Herbert returned to the SR as a director and died in 1949.

Alfred Raworth’s Electric Southern Railway is available to order here.