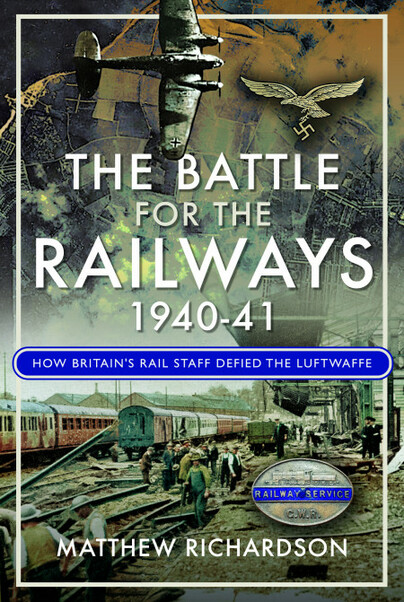

The Battle For the Railways, 1940-41

Author guest post from Matthew Richardson.

In 1939 Britain possessed the most concentrated and intricate railway system in the world, a system upon which everyday life and commerce depended. The Spanish Civil War in the late 1930s meanwhile had clearly demonstrated the effectiveness of (and destruction brought about by) the bombing of civilian targets. As war with Germany loomed ever larger, few could be in any doubt that such bombing of domestic infrastructure would play a significant part in this conflict as well.

Any serious attack on the British railway network from the air might prove to be disastrous, and as early as 1938 the London Midland Scottish Railway had drawn up emergency plans for the protection of its staff. These covered such topics as air raid organisation, warning systems, lighting restrictions, protective clothing and decontamination squads in case poison gas should be used. It was also realised that in order to deal with large scale damage such as the bombing of a major station, significant stocks of specialised material and equipment should be stored at convenient centres. This consisted of permanent way sections, timber, and steel joists as well as cranes, welding and cutting equipment. Major engineering work was also undertaken to try to increase the resilience of the network by adding extra lines to some stretches, and to reduce the number of potential choke points. For example, to the north of Carlisle where the main line from England to Scotland crossed the River Eden, a new bridge was built next to the existing structure to carry two extra lines. This would allow either to carry all traffic if the other was damaged by enemy action.

With the outbreak of war, the rail network was of even greater importance in keeping the country running, and ensuring that personnel and materiel where were they were needed. The ensuing conflict between the Luftwaffe and staff on the ground would become known as the Battle for the Railways, but before it even began, the difficulties imposed by the wartime backout on railwaymen were immeasurable. A Driver on an express locomotive had to know every inch of the road, not only every station, junction and signal but all his landmarks over 100 miles of line. When a train was travelling at sixty miles an hour there was little time to think, but the blackout meant that the countryside at night was plunged into absolute darkness, so that everything looked different. Every Driver and Fireman had to re-learn his bearings all over again. The Driver had to keep a constant watch on the road ahead, but the anti-glare curtains around the cab, aside from creating a turgid and unpleasant atmosphere, prevented him during the blackout from leaning out of his side window, so that his view was restricted to that through the front cab window.

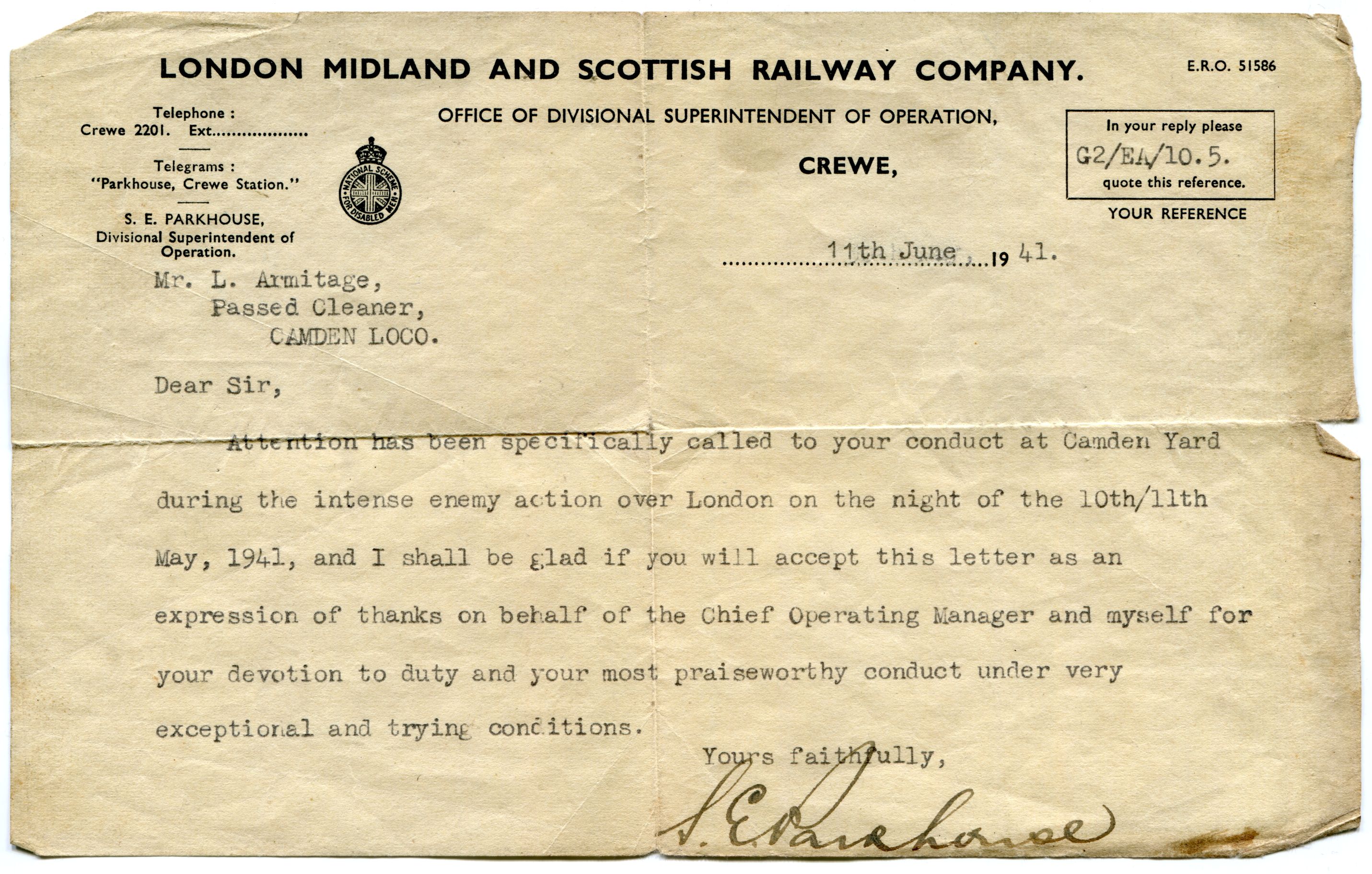

Many people today are aware of the impact of the Blitz in 1940-41, when Germany’s air force sought to terrorise the British people into submission through bombing of civilian targets. Few however are aware of how important the Battle of the Railways was in this. The determined efforts by the Luftwaffe to cripple the nation’s rail network were met by the herculean efforts of the railway personnel to keep the system running, in spite of the difficulties. Adolf Hitler was assured that air assault would bring Britain to her knees, but the Luftwaffe was not successful in this endeavour, partly because their attacks were sporadic and not strategically targeted, but mainly due to the often-unseen bravery of the railway men and women in keeping the network going. Normally during a raid the staff went to their shelters, but their sense of responsibility and duty was high, and often they were out before the ‘all clear.’ For many, they had for years taken great pride in their stretch of permanent way and day in, day out had ensured that its condition was second to none. Now this chap Hitler seemed intent on blowing it to bits, but that did nothing to alter their conviction or their dedication.

Because of its geographical location, the Southern Railway suffered disproportionately at the hands of the German air service during the early part of the Second World War. In terms of overall size, it was the smallest of the ‘Big Four’, and yet it received more damage than any of the others, both in absolute terms and in terms of incidents per 100 miles of track. Furthermore some 170 of its employees were killed whilst on railway duty. It was none the less a testament to the skill and determination of its staff that it was able to continue functioning so effectively, in spite of the repeated heavy attacks and enormous damage that it sustained during this period.

Hitler’s principal aim seemed to be nothing more than causing havoc, without any sort of plan. The simplistic belief of the Nazi hierarchy was that aerial terrorism alone would be sufficient to bring Britain to the negotiating table, and end the war on their terms. However, their grave underestimation of the British people – and the British railway personnel in particular – possibly lost them the war; it certainly lost them the Battle of the Railways. It is perhaps fitting to close this article with a poem written in 1940, at the height of the Blitz, by R.F.Thurtle. It is both apposite and moving:

Happy in peaceful service were our men

When the call came to some to leave awhile

The brake-stick, keying-hammer or the pen,

And take their stand within a martial file

They did not fail!

Flanders soon claimed them – seasoned men and young,

And proved their mettle on a testing ground;

In the red hells of Dunkirk, Calais and Boulogne,

Stern, valiant and unbroken were they found.

They did not fail!

England stands now, inviolate and at bay,

Alert and confident within her guarded coast,

And western men a worthy part will play

Through shambles be it or through holocaust.

They will not fail!

Matthew Richardson’s new book, The Battle for the Railways examines in detail this herculean but often overlooked struggle on the Home Front in the early month of the Second World War.