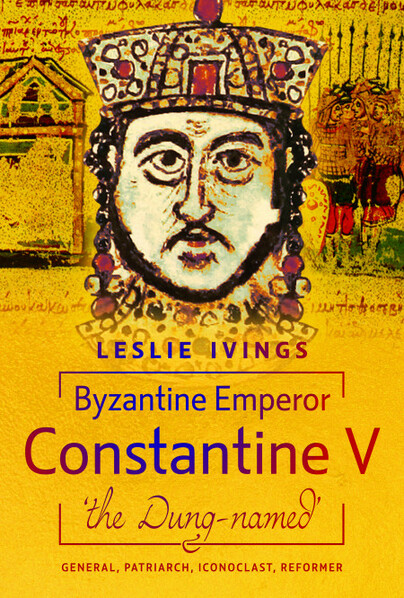

The Emperor They Loved to Hate: Rethinking Constantine V

Author guest post from Leslie Ivings.

In the shadowy corridors of Byzantine history, few emperors have suffered as strange and savage a posthumous fate as Constantine V. Upon his death in 775, this hardened general and reformer was interred with imperial dignity in Constantinople, praised by his soldiers and respected by the masses. Yet less than a century later, his enemies gave him a name that would cling to his legacy like rot to marble: “Copronymus” – the Dung-Named.

In writing Constantine V: ‘The Dung-Named’, I set out to uncover how one of Byzantium’s most formidable rulers became the victim of one of the most successful character assassinations in all of Roman imperial history. This is not only the story of a man but of an iconoclast, a tactician, a survivor and one of a deeper struggle over meaning and memory. The book explores how history itself can be shaped not by what a ruler does in his lifetime, but by those who survive him and write the record in ink laced with venom.

Constantine was born into the Isaurian dynasty and raised from infancy as co-ruler alongside his father, Emperor Leo III. He spent much of his early life training for leadership, immersed in both military strategy and imperial administration. As emperor, he built on Leo’s controversial religious policy of iconoclasm, the rejection and destruction of religious images and expanded it into a sweeping campaign of reform. To his allies, Constantine was defending orthodoxy against idolatry and restoring discipline to a drifting empire. To his enemies, especially in the church and the monastic establishment, he was a heretic and a tyrant. It is in the writings of those enemies that the character of “Copronymus” took shape, a mockery more than a man.

The origin of his infamous nickname comes from a malicious story that he fouled the baptismal font as a newborn. It was a fabricated anecdote, gleefully reported by iconophile chroniclers generations later, who had every reason to stain his memory. In their hands, Constantine was not simply a misguided ruler; he was cast as a monstrous figure, filled with rage, heresy, and even demonic possession. Yet when we look beyond the ecclesiastical polemic, we find a different story one of a capable and determined emperor, one who stabilised the empire, reformed the military, and beat back the encroachments of Arab and Bulgar foes.

He was, in fact, one of the most successful military rulers of the eighth century. His campaigns against the Bulgars were aggressive and, at times, brutal, and they were also effective, asserting Byzantine dominance at a time when the empire could easily have fractured. He restructured the themata (military-administrative provinces), boosted agricultural production, and ensured that soldiers were well provisioned and rewarded. In Constantinople, he was genuinely popular. Many sources, even those reluctant to praise him, admit that the general population mourned his death deeply. Crowds reportedly lined the streets to see his funeral procession, and even those who may have doubted his religious policies could not ignore his service to the empire.

So why was this same emperor remembered as a figure of filth and heresy? The answer lies in the deep divisions that plagued Byzantine religious life in the centuries following his death. The iconoclast movement did not end with Constantine. It continued, was overturned, revived, and then defeated again. With each shift in power, the legacy of previous emperors was rewritten to suit new theological agendas. By the time the iconophiles emerged triumphant in the ninth century, there was a vested interest in portraying Constantine as a cautionary tale, a warning of what happened when emperors set themselves against divine truth. His success had to be turned into a sin, and so the smear of “Copronymus” was adopted and amplified.

There is something deeply modern about Constantine V’s story. He was not brought down by the sword, but by the pen. He won battles, held together a fragile state, and defended a vision of imperial unity, only to be condemned by later historians who sought to turn the man into a symbol of everything they opposed. His downfall was not a coup or a rebellion, but a decades-long campaign of defamation, perpetuated by those who controlled the monastic scriptoria and ecclesiastical councils of memory. It is an ancient example of something we still recognise today: the war over public narrative. Or a Byzantine form of Cancel Culture.

What fascinated me most while researching this book was not simply Constantine’s policies or campaigns, but the way his memory was contested. I found myself returning to the question: how do we know what we know? Why do some emperors, whose reigns were disastrous, receive respectful treatment in the sources, while others, like Constantine, are buried under ridicule and myth? In writing this biography, I’ve tried to peel away the layers of satire, slander, and theological hostility to reach the man beneath. He emerges not as a villain or a saint, but as a capable and complex figure, ruthless, yes, and uncompromising, but also visionary in his way, and committed to the survival and unity of the Roman state.

Constantine V: ‘The Dung-Named’ is a book about a man, but it is also a book about how we remember, how we distort, and how we weaponise the past. It invites readers to think critically about the way history is written, and to question whether the stories we inherit are always the ones worth telling. For in the ashes of reputations destroyed by enemies, we sometimes find the clearest embers of truth.

Order your copy here.