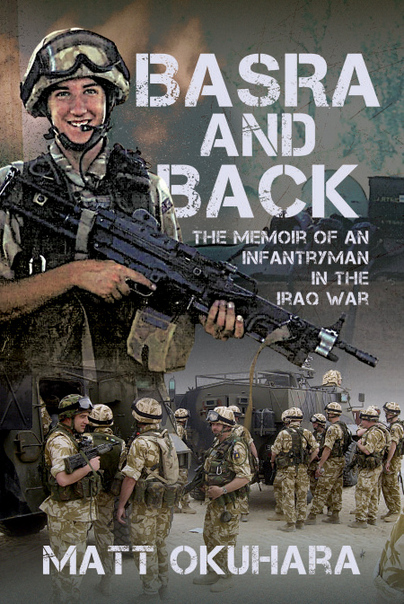

Behind the Scenes of Basra and Back

Author guest post from Matt Okuhara.

We expect war books to be loud. Explosions, firefights, heroism, maybe a dash of trauma. Basra and Back isn’t that kind of book. There are no clear villains, no grand speeches, no final act redemption. Just soldiers, sweat, kit that doesn’t work, and days that blur together until one of them doesn’t.

Writing this book, I wasn’t interested in glorifying my time in Iraq, nor was I trying to unravel it with psychological analysis. I just wanted to tell the truth as it was lived: fractured, human, occasionally surreal. A truth built from the space between incidents—the waiting, the joking, the broken air conditioning, the calluses, the tea-making, the injuries that get ignored.

Most of soldiering isn’t combat. It’s routine. Paperwork. Route planning. GDA patrols. Stacking sandbags. Checking fluid levels. You do the same things every day, until something snaps—someone passes out, an IED goes off, or you get a knock on the door telling you the general wants a brew and you’re the “chatty little twat” who’s been picked for tea duty.

It’s this rhythm—boredom cut with bursts of chaos—that defines life on deployment. It’s what I tried to capture. The reality that the body breaks before the spirit does. That blood and sweat matter as much as bullets. That grief sometimes arrives in the form of a woman screaming outside a hospital, then disappears without explanation.

There’s a lot about war that doesn’t make sense until later. Why we patrolled in Northern Ireland-era Land Rovers in southern Iraq. Why private contractors had better gear, better sunglasses, and better pay, despite doing what looked like less work. Why a cracked thumbnail from a slammed vehicle door hurt worse than some wounds we treated in the field.

There’s no single message in Basra and Back, but there are questions. What is a soldier worth? What do we carry home with us? Who gets remembered, and who gets written out? These aren’t grand political arguments—they’re the kinds of things you think about while sweeping sand out of a ready room, or watching Love Actually for the fifth time because someone broke the DVD player again.

One question I get asked is whether the humour in the book is a mask. “Isn’t it all just deflection?” Maybe. But I don’t think so.

The dry humour, the swearing, the mockery—it’s culture, not coping. It’s how we talk to each other. How we survive the job, the heat, the boredom, the absurdity of taking enemy fire in one hour and cleaning blood out of your kit the next. It’s not a punchline. It’s punctuation.

When Uzi asked me to pop the blood blister under his nail with a red-hot needle, it wasn’t about being tough. It was about trust. About not making a big deal of pain. About knowing that the job carries on, and you still have to carry the ECM, even if your thumb’s fucked.

I didn’t write Basra and Back to make a political point. But I can tell you this: the people on the ground always know more than the posters in the recruiting office. We know what works and what doesn’t. We know what it means to carry weight, to drag stretchers, to sweat through the night, to get handed a commendation that doesn’t match what we remember.

This is a book for those who were there—and for those who weren’t but want to understand. It’s not tidy. Neither was the war.

It’s a collection of moments. Stitched together like torn webbing. Held in place with a bit of sports tape and dry sarcasm. And if you’ve served, or worked alongside those who have, you’ll recognise the smell, the sound, the shape of it.

You’ll know this story, even if it wasn’t yours.

Order your copy here.