Author Guest Post: Helen Frost

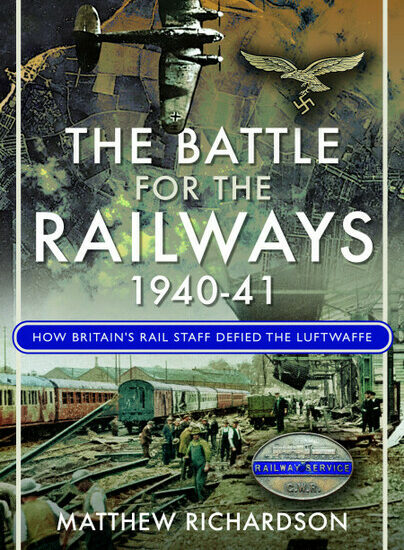

Voices From the Great War Women’s Land Army.

10 points to consider about the forgotten first crop!

By Helen Frost.

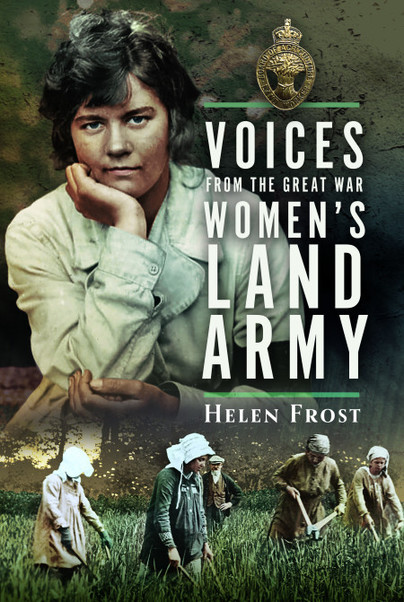

The first time that I saw a photograph of a Great War Land Girl, it quite literally stopped me in my tracks. I studied the expression on her face as she proudly and confidently posed for a studio portrait; one of pride, composure and stoicism. I also noticed that she wasn’t looking directly at the camera. Purpose above vanity perhaps.

It was a pivotal moment that kick-started further research but one that also propelled me headlong into the world and times that this inspirational ‘army’ of women lived in and worked through.

-

The Women’s Land Army of the Great War was pioneering in the sense that it not only managed to break through rigid class barriers and conventions of the society of the day but also that the women who joined it had to continually strive to overcome prejudice from men and women. Entrenched societal views attempted to hinder their progress. Gender stereotypes of the day also determined, (to an extent) the jobs that a woman could and in fact should do.

-

This relatively small army of officially enrolled women, (23,000 at its peak, although some figures differ) were in the main, drawn away from stable, well-paid employment, university or made the decision to leave a comfortable, sometimes sheltered background in order to work for the first time in their lives.

Recruitment was predominantly aimed at middle to upper-middle class women for whom working on the land would almost certainly be a new experience. It is estimated that between 300,000-400,000 women came forward to work on the land having never done so before for all manner of reasons. Their contribution is often never recorded in any documents or records.

In contrast, women at the other end of the social scale who were in domestic service, (often born into large families) saw the opportunity for a new challenge and an escape, albeit from one type of exhausting work to another!

-

Many women, although finding the work incredibly hard physically were actually able to cope with it and quickly earnt respect from the men they worked with. For others, the laborious manual work proved too demanding and they didn’t remain in land organisations or the Women’s Land Army for very long due to their preconceived, idealistic expectations not actually being borne out in reality.

It was to the astonishment of many farmers that such women readily rolled their sleeves up and consented freely to take a drop in their wages to stave off potential starvation in Britain. The patriotic need to serve and motivation that drove the Women’s Land Army, (to assist with and to maintain food production and supply during a prolonged conflict) became its appeal and was in effect one of the same driving forces behind what prompted men to serve too.

-

With the Great War dragging on into its fourth ghastly year, food shortages were biting ever harder into civilian life. Due to a hugely successful German U-boat campaign that by 1917 was targeting merchant ships, (as opposed to warships in 1915/1916) food shortages were becoming severe in both urban and rural areas. Starvation was a genuine threat and sadly for some, a grim reality by 1917 hence the urgency to form a regulated, civilian landworker organisation. The Women’s Land Army was the result. This was an army that had no precedent as there had not been a crisis quite like the one that faced the country at the time.

-

A name that blazes out from the history books is that of Meriel Talbot or Dame Meriel Lucy Talbot DBE as she became. Meriel came to nationwide prominence as the first female Director of the newly-formed Women’s Branch appointed by the then Minister of Agriculture, Lord Selbourne.

For this army of women to be taken seriously and attract recruits, it had been decided that it needed to be ‘run by women, for women.’ Hindsight tells us that this was indeed a sagacious decision but could the momentum generated be maintained after demobilisation?

-

Recruitment rallies took place in towns and cities across the nation. Parades of recruits strode out in their practical landworker uniforms, (the likes of which had never been seen before) holding banners aloft with stark statements on them, ‘The food you grow is better than the food produced by others.’

Also terms like ‘You can join the Land Army for six months’ enticed and attempted to persuade the unsure to come forward. Initially women who signed on the dotted line signed up for the duration of the war but this had an obvious effect on the numbers of women who were coming forward so the terms were soon changed.

Women could volunteer either at the rallies or go to Post Offices and Employment Exchanges to apply for the enrolment forms.

Obtaining three references slowed down the recruitment process, leading many women to be employed privately or in an ‘unofficial’ capacity. Candidates would appear before an interview panel and require a medical too. Their mental and physical suitability for work was also assessed at this stage too. The rejection rate stood at roughly 50% of the 45,000 women that initially applied to serve.

If a woman had previous training, she would be placed almost immediately on a farm. If not, they would be sent to a training centre, (247 of these had been set up all over the country by late 1917). Wealthier women were often experienced horsewomen and their skills were put to good use in the many remount depots.

-

The isolation however that many recruits felt and the frequent lack of acceptance into tightly-knit rural communities proved a hard obstacle to overcome for some women. Years later, women still often recalled feeling barely tolerated.

For others, the pull of their childhood spent in the countryside drew them back, (many had grown up living in workers’ cottages on country estates). Others eventually married countrymen and remained in the countryside. Despite these fond memories, being in good health and of a strong disposition, they often admitted that they hadn’t fully realised the extent of what the Women’s Land Army was going to ask of them. They had often worked for hard taskmasters which over time, inevitably proved too much for some women, who saw their health deteriorate.

-

It was also thanks to the efforts of civilians, who, through campaigns such as ‘The Allotment Campaign’ also produced huge amounts of extra food on allotments and smallholdings. In addition, the new labour force of women who had joined the Women’s Land Army enabled the production and gathering of a successful potato and wheat harvest in 1917, (prices subsequently halved of potatoes).

-

Women also had options after they were demobilised on November 30th 1919. They were encouraged to remain in farming. They were also offered settlement overseas in various countries; an offer which some women gladly took up. Others joined the newly set up National Association of Landswomen and seized the continuing opportunities offered to them with both hands. Many of course opted to return to their former occupations.

In just a few years, all of the women in their own individual way made such a significant contribution to the war effort.

These women literally stepped into the shoes of menfolk where it was possible to do so. They remain inspiring, relevant and are great role models, (with few exceptions) to this day. They deserve recognition and to be rightly remembered alongside their later counterparts.

-

Awards were given at the time for long and good service, devotion to duty and bravery whilst serving. But as the intervening decades passed by the contribution that they made to the nation at a time of genuine crisis is rarely commemorated in the same breath as their later counterparts. They are remembered in words but not bronze on the Women’s Land Army Memorial at The National Memorial Arboretum at Alrewas, Staffordshire.

It should however be remembered that they were indeed the first, vital crop of ‘awakened women’ which undoubtedly paved the way for their later counterparts.

14 Land Girls take part in Tank Week as part of a recruitment drive in Doncaster during the summer of 1918. They are each wearing letters on their back which spell out the words F.O.O.D P.R.O.D.U.C.T.I.O.N. They are walking alongside Egbert the fundraising tank.

The Landswoman, June 1918, p11. Copyright: Successor rightsholder unknown.

‘Voices From the Great War Women’s Land Army’ not only tells of so many quirky, unusual, funny and challenging stories about their life in service but also includes all 56 recipients of the highest honour that was awarded to those who had shown bravery and devotion to duty or the organisation itself. The ‘Distinguished Service Bar’ was known informally as the ‘Land Army VC’ but it is little known about today.

Lest we ever forget what these women did.

Order Voices from the Great War Women’s Land Army here.