Author guest post: James Goulty

A Sailor’s War during the Campaigns in the Mediterranean, Normandy and Far East, 1942-1945

The Royal Navy played a significant role in almost every campaign of the Second World War, including gaining considerable experience of opposed amphibious landings that were notoriously complex and difficult to master According to the historian Eric Grove, overall it fought well and ‘its capacity to learn from experience and apply new technology had been second to none.’ Eventually around one million men and women would serve with it, many of whom were volunteers or conscripts. By August 1945 the Royal Navy had lost over 50,000 personnel, and 1,525 ships and smaller vessels. This included the battlecruiser HMS Hood, sunk in an engagement with the German Bismarck south of Greenland, and the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal which was torpedoed by U-81 in the western Mediterranean during late 1941.

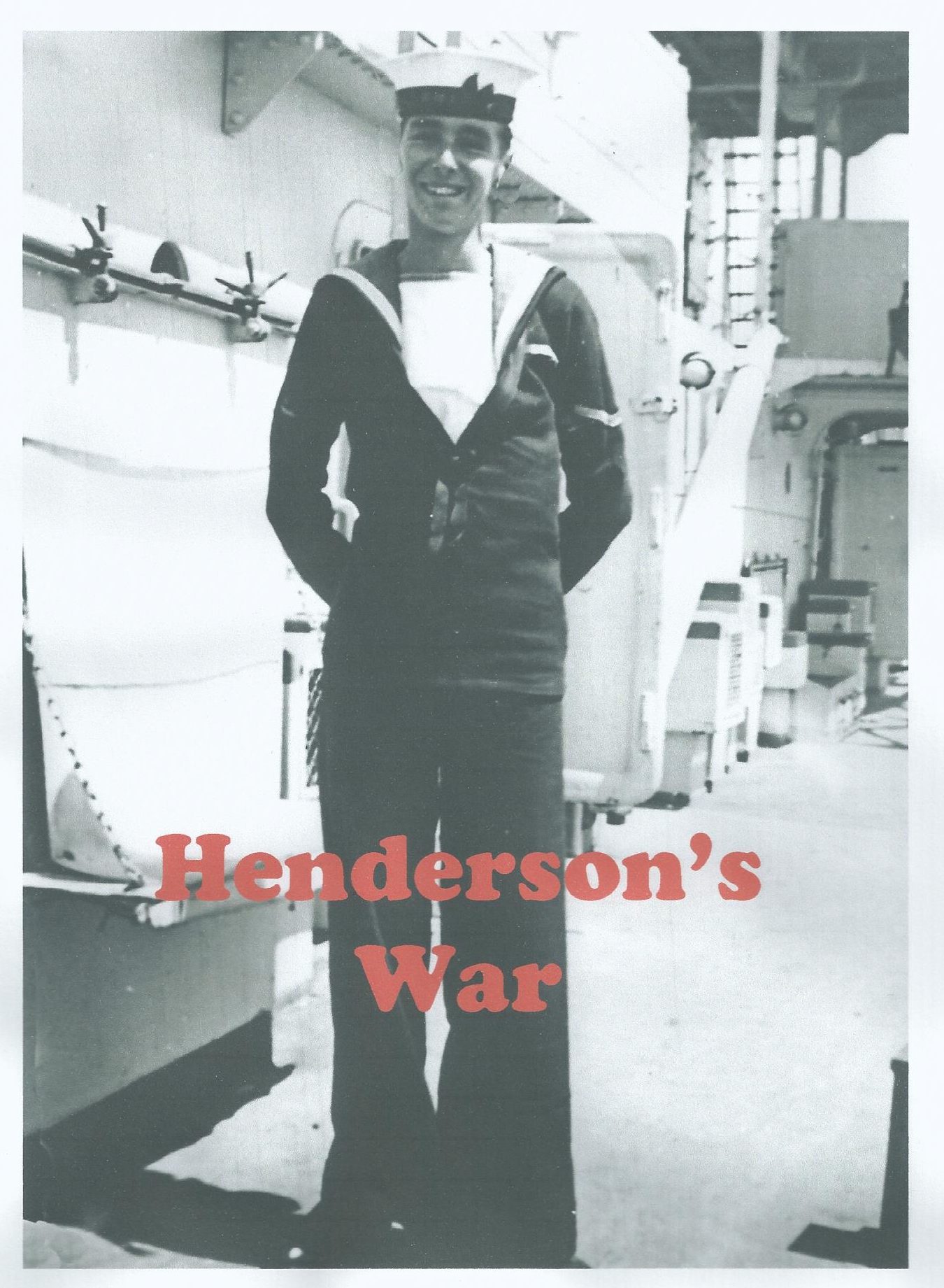

When war was declared in September 1939, George Henderson was 15 years old and worked for his local Co-Operative Store in Newcastle upon Tyne. He recalled it was ‘a beautiful Sunday morning’ and everyone feared that a German invasion of Britain might be imminent. Instead nothing appeared to happen, particularly on land during the autumn/winter of 1939-1940, a period the press dubbed the ‘Phoney War.’ However, at sea during this period there was some significant activity, including the sinking of the battleship HMS Royal Oak by U-47 which had succeeded in penetrating the British naval base at Scapa Flow. The Battle of the River Plate also witnessed the scuttling of the German Graf Spee by her crew when she was cornered by British cruisers in Montevideo. As a teenager George became aware of these incidents and was keen to join the Royal Navy, despite having no family ties or other connections with the ‘Senior Service.’

To cope with wartime conditions the British government re-introduced conscription. On the first day of war (3 September 1939) the Military Training Act was superseded by the National Service (Armed Forces) Act that made all British male subjects aged 18-41 liable for military service. Many men, including George, chose to volunteer for the Armed Forces rather than wait to be called-up, and the navy proved particularly popular amongst would be recruits. Partly this was because the navy had a heroic image, and as historian Brian Lavery commented, there was a public perception ‘that officers and men were closer on board ship,’ and that ‘everyone from admiral downwards shares the danger.’

George recounted ‘as a 17 year old I was determined to join the Royal Navy even though I had a father who had been in the army.’ As a trained joiner, his father had transferred to the Royal Flying Corps because his trade enabled him to work on aircraft. By the time George tried to join the navy in the Second World War, his brother was serving in the army, and was tragically killed in action during the North African campaign. Consequently, George’s enlistment into the navy was deferred on compassionate grounds.

Eventually he was posted to HMS Collingwood in Hampshire where he underwent basic training. This had opened in 1940 and dealt exclusively with drafts destined for the Portsmouth home port division. Historian Brian Lavery highlights that wartime naval basic training syllabuses seldom involved contact with ships, although recruits might see them from a distance. Rather the onus was on learning discipline, simple skills, and physical fitness. Foot drill or ‘gravel grinding’ as it was termed in the navy, was a key part of the basic training regime. Recruits also became accustomed to wearing the ‘square rig,’ the standard blue naval uniform for ratings in the Royal Navy, that became a model uniform for many other navies.

With some relief George passed his basic training course during 1942-1943, and eagerly awaited a posting. As he explained ‘it was in the lap of the gods as to where you could be sent. It might be battleships, cruisers etc.’ He discovered he was to travel to America in order to pick up a newly manufactured landing craft from her ship yard, and sail her as part of a convoy back to Britain.

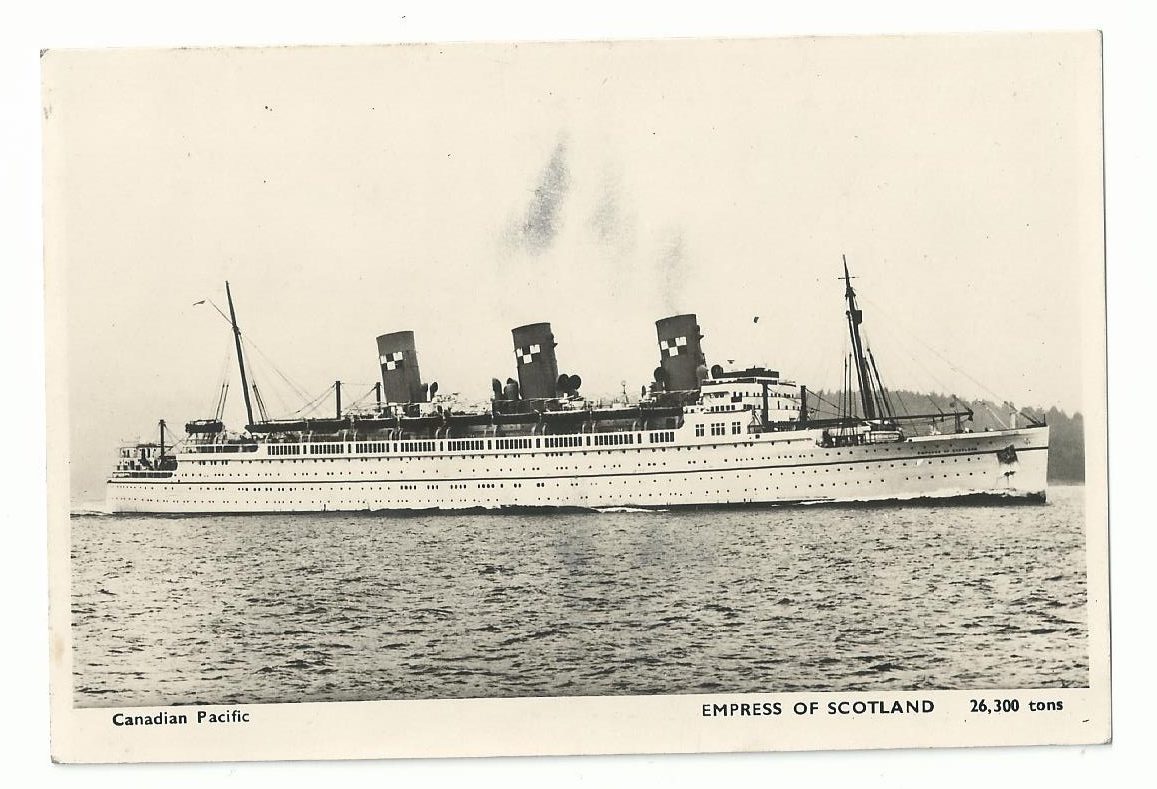

Initially this entailed a lengthy journey on a trooper or troopship, the Empress of Scotland (formerly Empress of Japan), from Britain to New York. As it was his first time at sea, George struggled to adjust to conditions aboard ship. He and a mate were violently sea sick. Once they both felt well enough to eat they went to the ship’s canteen, and ended up purchasing some chocolate. They duly consumed this with some trepidation, and both were very ‘surprised to discover that even though you wouldn’t think it, this seemed to cure them of their sea sickness.’

After crossing the Atlantic, they stayed in the New York area and George remembered ‘we had a grand time and did the rounds well, cinemas, shows, ice skating, bands etc.’ They were then taken by train to New Orleans, where George and his crew mates were ordered to take over a Landing Ship Tank (LST), before returning to New York to load up with tanks and troops.

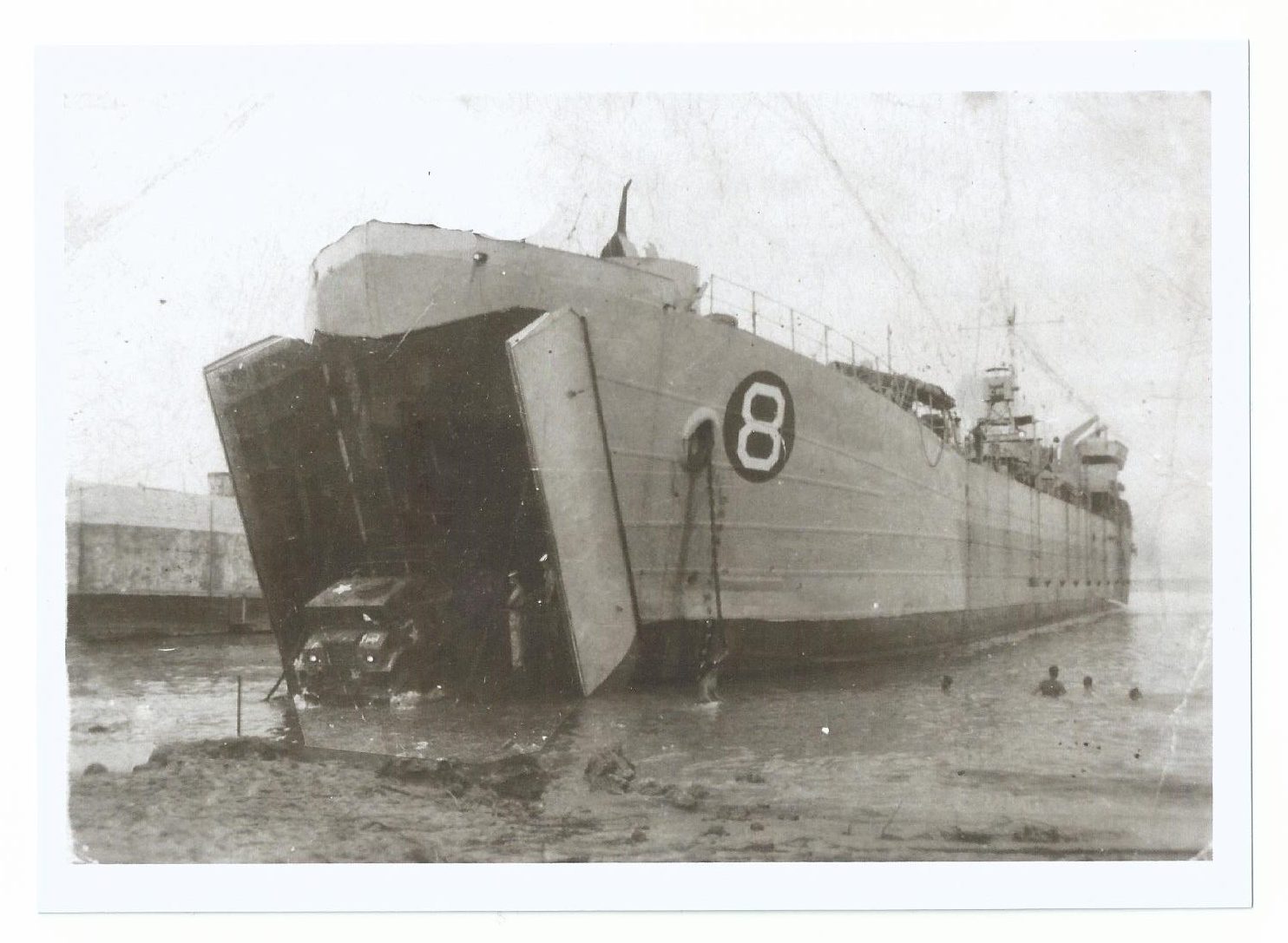

As early as July 1940 Prime Minister Winston Churchill, had foreseen the need for major amphibious operations as part of Allied strategy, and stated: ‘Let there be built great ships which can cast up on a beach in any weather large numbers of the heaviest tanks.’ The LST was a response to this requirement, and these vessels helped considerably in making viable the Allied plans for a return to the European mainland. By 1943 large numbers of LSTs were being manufactured in America, and made available to the Royal Navy under the Lend/Lease scheme. This included LST-8 to which George was posted. She was laid down by the Dravo Corporation, Pittsburgh PA in late July 1942, and launched the following October before transferring to the Royal Navy in March 1943.

The cargo carried by LSTs varied depending on their particular mission, but typically they were capable of handling pay loads of around 1,600 – 1,900 tons. At over 300 feet in length and 50 feet wide, with a maximum speed of around 12 knots, LSTs were sometimes dubbed ‘large slow targets’ by their crews and other personnel. Many years after the war, George admitted that ‘there was much truth in this nick-name as effectively we really were large slow targets.’

LSTs proved comparatively versatile vessels, and while designed principally to transported tanks, they could handle other loads, including wheeled and tracked vehicles, artillery, construction equipment, military supplies and even small landing craft to be deployed during an amphibious assault. There was accommodation available for approximately 150 soldiers and their officers. George explained ‘it could take 2-3 hours to load up as for the upper deck there was a lift that had to be assembled.’ Here smaller vehicles such as trucks and jeeps could be carried while ‘the heavy stuff’ was put on the lower deck.

At times LSTs were deployed to evacuate wounded troops. Peter Lovegrove in Not Least in the Crusade: A Short History of the Royal Army Medical Corps (1951) observed, that in Normandy LSTs were run straight onto some beaches and ‘had folding racks fitted in tiers along the sides which could accommodate 350 lying cases.’ Approximately 50 per cent of LSTs had naval medical staff aboard, who started treating casualties, almost immediately after tanks and vehicles were unloaded.

According to George the co-operation between sailors and soldiers was usually very good. ‘We liked to look after them,’ and this included sharing navy rations which were much better than those issued to the army. However, ensuring that loads aboard LSTs were adequately secured for sea voyages was a constant challenge. Although he recorded no serious issues in this regard arising during his service aboard LST-8, there were occasions aboard other LSTs where loads broke free causing problems. In his memoir In the Face of the Enemy (2008), Battery Sergeant Major Ernest Powdrill of the Royal Horse Artillery, recounted a serious incident during a crossing to Normandy in 1944 aboard an American crewed LST.

The eccentric wallowing of the ship had caused some of the tanks and guns to break loose from their deck chains, causing them to crash sideways into each other as the ship lurched this way and that. The tank deck was awash with seawater about 2 feet deep. Water poured in from the ramp aperture, …it had not been properly secured. As the tanks collided…they crushed many of the Jerrycans full of petrol that had been strapped to the outside of the vehicles. The result was a noxious mixture of seawater and petrol giving off choking fumes that made breathing difficult.

LSTs had a shallow draft enabling them to negotiate gently sloping beaches so tanks could drive off safely via a ramp and large doors in the bows. Simultaneously, they were rugged enough to withstand ocean going conditions, although owing to their design they had a marked tendency to roll, especially in rough weather. George found his first voyage aboard LST-8 was ‘terrible’ owing to the movement of the ship, but after a while he confirmed ‘you started to get your sea legs.’

Once it had beached, a LST could kedge itself back into deeper water after discharging its load. As George noted you tended to ‘head into a beach as hard as you could with stern anchor deployed, bow doors open and land tanks etc. Then pull on the anchor to extricate the LST.’ Alternatively, it was possible for LSTs to deploy pontoons carried either side amidships and form what were known as ‘Rhino barges’ or a causeway. These could be married to the bow ramp and enabled vessels to unload from deeper water, or where the beachhead did not allow for the LST to be grounded after ballasting.

On 14 May 1943, LST-8 sailed from America for an ‘unknown destination.’ There was a belief amongst the crew that she was expected to head for Britain. Instead Convoy UGS8A of which she was a part was diverted to the Mediterranean. By now both the siege of Malta and the campaign in Tunisia were reaching a climax. In early June George remembered arriving off the coast of North Africa, near Oran after a ‘3 week voyage that covered over 4,000 miles.’

Soon George became involved in convoys bound for Malta. The island had played a pivotal role in the war in the Mediterranean, owing to its strategic position and was under siege by the Germans and Italians during 1941-1943. During April 1942 Malta’s airfields alone received a weight of bombs that was 27 times greater than the devastating raid on Coventry in October 1940.

The experience of these Malta convoys left George with a deep respect for the Merchant Navy who suffered grievously. It was ‘painful to watch their ships being hit, especially those carrying ammunition’ which exploded violently with ‘a terrific crump.’ As it proved impossible to stop to rescue casualties this tended to increase still further the strain of these operations.

Runs to Malta exposed LST-8 to aerial attacks by both German and Italian aircraft, and the threat of U-Boats patrolling the Mediterranean. On Saturday 26 June 1943, George recalled being attacked by fighter bombers and U-boats. One of the latter was sunk by the ‘L’ class destroyer HMS Loyal that was later mined in the Adriatic. George recalled: ‘She dropped depth charges in the middle of the convoy and when the ‘sub’ came up she burst into flames. This brought heavy bombers into the attack which lasted until 11pm. We had some pretty near misses and a lively time was had by all.’

Coming under air attack was clearly a nerve wracking experience. Sometimes as George discovered you could spot enemy aircraft like ‘glinting silver dots coming out of the sun,’ but other times there was less warning. The crew of LST-8 were relatively powerless to do much to counter the threat. There was a 12 pounder gun mounted in the stern and six 20 mm anti-aircraft guns positioned around the ship. George considered these could put up a seemingly impressive level of fire, but this was more of a ‘morale booster’ than anything else.

Many LSTs were also equipped with a limited number of mounts for Fast Aerial Mines (FAM). These worked by firing a rocket trailing a wire at low flying enemy aircraft, and if the wire made contact with the aircraft a grenade was launched that exploded on impact.

George vividly recalled that LST-8 had a shark-finned barrage balloon aboard operated by a small RAF contingent, and intended to hinder low flying enemy aircraft. Even so, it sometimes proved a liability rather than an asset. Once he witnessed it was punctured so that it ‘went mad like a child’s party balloon,’ and had to be chopped down with an axe because it proved too cumbersome to wind down manually.

During July 1943 George became involved in Operation Husky, the Allied assault on Sicily, as LSTs were urgently required to land vehicles, troops and stores directly onto the invasion beaches. The British 8th Army, including Canadian troops, landed in the Pozallo, Noto and Syracuse region in the south-east, and the US 7th Army at Licata and Gela farther west.

Again voyages to Sicily exposed LST-8 to air attack, and years later George would bemoan the lack of effective air cover provided to the Allied naval forces during the operation. On Wednesday 18 August 1943 he recorded: ‘Another raid last night, some very near misses! Nearest we have been yet to getting wiped.’ Similarly, on Saturday 28 August he demonstrated that air attack was becoming a routine phenomenon as there were ‘several raids by fighter bombers again.’

As well as seeing action, by late 1943 George was becoming accustomed to daily life aboard LST-8, and what this entailed as a seaman. Watches of 4 hours on, 4 hours off night and day were interspersed by the dog watches from 4-6 am and 6-8 pm. There was a crew of around 80 men including a handful of officers, stockers, signallers and stewards. However, the bulk of the crew was comprised of seamen like George. Officers and ratings had separate messes, although when in action little time was spent there.

Typically, his duties entailed keeping the ship clean, rearming the anti-aircraft guns, and washing out decks at the end of each voyage. As he observed transporting large numbers of soldiers, vehicles and supplies tended to generate ‘a fair degree of mess and many troops suffered badly from sea sickness.’ Consequently, it was always necessary ‘to get the hoses out, clean the ship and prepare for yet another trip.’ Likewise, at times it was necessary to scrap the ship’s bottom, and repaint her sides, which could prove a lengthy process, and it fell to ordinary seamen to conduct this work.

Sicily witnessed some extremely bitter fighting during the summer of 1943, often in rugged terrain and with troops suffering casualties from malaria as well as enemy action. Finally on 11 August the enemy showed signs of withdrawing and eventually 100,000 German and Italian troops, plus 10,000 vehicles escaped across the Straights of Messina. A logical next step for the Allies was the invasion of mainland Italy, viewed by Winston Churchill as the ‘soft under belly of Europe.’

On 3 September Montgomery’s 8th Army crossed from Sicily to land in the Reggio Calabria area in the toe of Italy. LST-8 took part in these landings and as George commented in his private log on Friday 3 September: ‘4 years today since the war began, celebrated by landing early this morning at Reggio. 2 raids by fighter bombers.’

Subsequently, LST-8 was assigned to those naval forces supporting the main Allied landings at Salerno, south of Naples. As George discovered this was a tough assignment because ‘the army was stuck on the beach.’ The German defenders were on the alert and had constructed several well-sited defensive positions, plus armour from 16th Panzer Division had been moved towards the coast. The announcement of an Italian armistice on 8 September also enabled the Germans to disarm their former allies. Although the British and American troops eventually broke out of Salerno, the fighting was severe with around 15,000 Allied and 8,000 German casualties.

George did several trips to Salerno, and his private log provides a clear impression of the ferocity of the fighting, particularly from a naval perspective. Allied shipping was routinely subjected to air attacks. Wednesday 15 September: ‘2 LCT’s [Landing Craft Tank] sunk and 1 Liberty ship damaged this morning by high level and fighter bombers.’

Carrying ammunition for the troops struggling on shore was another task that relied on the manoeuvrability of LSTs to bring it straight onto the beaches. Thursday 16 September: ‘Arrived at Termini. We loaded up with troops and 500 tons of ammunition this time, just like sitting on an ‘ammo’ dump.’

On one voyage to Salerno, LST-8 suffered damage to her starboard bow door, necessitating repairs at Bizerta, North Africa. This allowed George and other crewmen to enjoy 48 hours leave in Tunis where they ‘had a pretty good time.’ They were cheered by the news that they might shortly be heading home, even if it proved necessary to ‘complete a few more trips first.’

Yet, during October/November 1943 it became clear that thoughts of returning to Britain were premature. LSTs were still urgently required to support operations in Italy. On 3 November George recounts that the ‘Captain cleared the lower deck to tell us that our departure for home had been postponed for a month.’ At least he was lucky enough to receive 33 letters when a bag of mail had finally caught up with his ship.

During the winter of 1943 life aboard LST-8 continued to be dominated by the demands of the Italian campaign. On one occasion 150 former prisoners of war were brought back to North Africa, many of whom had escaped from POW camps and walked down Italy evading the German forces on the way. However, there were moments away from action when the crew of LST-8 enjoyed brief spells of leave. A trip from Bizerta to Taranto in late November was followed by a few hours leave in that city, which George described as ‘very nice and there are a few clubs for us.’

Coping with the weather at sea was a perennial challenge for the crew of LST-8. Tuesday 30 November: ‘Still choppy. Head on sea is knocking us about a bit. We are making very poor speed.’ On Saturday 11 December George recorded: ‘Bad weather! We are rolling like a barrel.’ On one voyage in the Mediterranean he was required to take the wheel during rough weather with the ship listing at 30 degrees. Under such conditions it proved exceptionally difficult to steer. The ‘skipper even rolled out of the small bunk in the wheel house he used when in action.’ However, at other times George found that the sea was much calmer and even appeared ‘smooth.’

Christmas 1943 was marked by a ‘grand tea and supper’ during which the captain and officers came down to the mess deck and toasted the crew’s health. There followed ‘a sing song from 11pm to 2am’ and on Boxing Day there was an Army v Navy football match which the latter won 8-1. Occasions such as this often allowed ordinary servicemen a chance to watch former professional footballers who had been called-up, often including some of the big names of the day. George fondly remembered seeing the Welsh International inside forward Bryn Jones playing for the army on that day.

During late December and early January LST-8 continued to mount voyages in support of troops bogged down in Italy. She was then deployed during Operation Shingle, the Allied amphibious landings at Anzio. Given the deadlocked on the Cassino front, the plan was for a landing behind the German lines, which it was hoped would facilitate the Allied advance up Italy. This proved optimistic, and the continued stalemate at Cassino resulted in Anzio becoming a full scale offensive as well, lasting from late January until late May 1944, when the forces advancing from Cassino finally linked up with those at Anzio. The fighting was extremely savage at Anzio and resulted in over 25,000 Allied casualties, and approximately 40,000 German.

George completed several trips to the Anzio beachhead, generally operating from Naples where the invasion force was marshalled. He remembered that unloading LST-8 was often helped by being able to use the harbour facilities at Anzio, so that troops and vehicles could exit directly via the ramp onto a jetty. As with other operations in the Mediterranean the threat of air attack was often encountered by the crews of these ‘large slow targets.’ They were particularly vulnerable while waiting off shore before coming in to unload. On Wednesday 26 January 1944 he observed: ‘Arrived early morning and lay in bay, there were quite a lot of raids. We had a night raid and it was pretty hot, went into harbour about 4 am and unloaded.’

Around 60 LSTs were made available to support the Anzio landings, but tensions within the Allied high command ensured that this number rapidly dwindled as these vessels were urgently required for the invasion of Normandy set for June 1944. Negotiations between the British and Americans involved factors such as sailing times, crew training, and the refurbishment of ships. However, they ensured that some LSTs would remain in the Mediterranean, so long as they sailed to Britain by 11 May 1944.

LST-8 was one of those vessels that remained in the Mediterranean, but in late March 1944 as George recalled the crew were delighted to hear from their Captain that they would soon be part of a convoy heading for home. This was after over a year of more or less continuous active service. On Saturday 22 April George eventually: ‘Sighted shores of England or I should say Wales as we are bound for the port of Swansea. What a grand sight to see ‘Blighty’ again.’

Rapidly he discovered that LST-8 was to undertake beaching trials ahead of the Normandy invasion. This was met with consternation by the crew, as after all they had already gained extensive experience of amphibious operations in the Mediterranean. Their displeasure increased further when they discovered that they were not even being granted any significant leave after returning home from overseas.

Operation ‘Neptune,’ the naval component of the Normandy landings, was a massive undertaking, and relied heavily on the Royal Navy which provided the majority of the vessels employed. This included those involved in the bombardments, those covering and escorting the invasion force, as well as many of the landing ships and craft. Of the 2,468 major vessels deployed on 6 June 1944, only 346 were American.

LST-8 was tasked with bringing Canadian units ashore at Juno Beach. A further impression of the complexity of the operation can be gained from Field Marshal Montgomery who outlined the task that faced the Allies during an address he gave in late 1945. Cross Channel invasion ‘meant the export of a community the size of Birmingham. Over 287,000 men and 37,000 vehicles were pre-loaded into ships and landing craft prior to the assault, and in the first 30 days 1,100,000 British and American troops put ashore.’ By 1944 the Allies could draw upon experience of amphibious operations in the Mediterranean and Pacific theatres, and were desperate not to repeat the mistakes of the disastrous Dardanelles campaign during the First World War.

During the summer of 1944 George completed several cross Channel trips in support of the Allied armies in Normandy. On one voyage he vividly remembered that they towed part of a Mulberry harbour across attached to their stern. The Allies realised it would be extremely difficult to seize a Channel port to support the invasion. Instead the solution was to rely on artificial harbours code named Mulberries. These comprised over 200 sections, the largest of which could be towed across the Channel and sunk to form harbour walls. Within the shelter of these various pre-fabricated piers and floating road ways on pontoons were established, that could be used to bring men and material ashore as the build-up in the Normandy bridgehead continued.

By late 1944 the Normandy campaign was finally over, and British and Canadian armies were advancing into the Low Countries, confronted by a German enemy who although retreating was still capable of putting up considerable resistance. Consequently, it would be sometime before North-West Europe was finally liberated. However, the rapid capture of Antwerp, with most of its port facilities in tact, by the British 11th Armoured Division was a distinct boost to the Allies. Subsequently, Royal Navy minesweepers helped clear the Scheldt, and once Antwerp was operational and it proved possible to land thousands of tons of stores from big ships.

Under such conditions LSTs were in less demand than they had been during the Normandy invasion, and many including LST-8 were redeployed to the Far East. Here she was to take part in Operation Zipper, the proposed invasion of Malaya. Ahead of sailing to the Far East, LST-8 underwent a refit at Liverpool during September 1944, and it was at this time that George left the ship.

He was then posted on a torpedo course at HMS Vernon, the navy’s torpedo school. In 1940 this had moved from Portsmouth to Roedean girl’s school near Brighton, largely to escape Luftwaffe raids on that city. It became well known within the navy for a sign in the dormitory which read ‘if you require a mistress in the night, ring the bell.’

According to historian Brian Lavery, the main Seaman Torpedoman qualifying course taught personnel ‘how to charge the weapon with air and electricity, to transport it and its warhead, to carry out various maintenance tasks including oiling, to operate torpedo tubes and deal with misfires, to fit and maintain the gyroscope and to make final adjustments before firing.’ In other words they were given a thorough working knowledge of the torpedo and how to care and maintain it, although they were not actually responsible for deploying the weapon in action.

Having qualified as a Seaman Torpedoman, George was posted to HMS Wolfe, which had been requisitioned by the Admiralty in 1939 for service as an armed merchant cruiser, and subsequently converted into a submarine depot ship. By late 1944 she was operating from Trincomalee in Ceylon (Sri Lanka), as part of the Eastern Fleet in support of the 2nd Submarine Flotilla. Submarines from that unit conducted offensive patrols against Japanese shipping in the Indian Ocean and Malacca Straits, reconnoitred potential landing areas, and landed intelligence personnel engaged on covert missions. As a depot ship HMS Wolfe provided repair facilities, and logistical support for the submarines, plus accommodation for relief crews. Without ships like her, the navy simply would not have been able to operate effectively in a distant theatre such as the Far East.

Even at this late stage in the war, the Japanese were still a formidable foe. Like many servicemen, George feared he would not survive if his ship was involved in any invasion of Japan. Consequently, when HMS Wolfe was ordered to take her place in a vast armada being assembled by the Allies he feared the worst. He was extremely relieved when the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during August 1945 that ended the war. Viewed 70 years on this might sound callous, particularly given the numbers of civilian deaths, but as George explained ‘at the time it did not look as if the many ships in the invasion fleet would have survived, and they [the Japanese] did start the war.’ Had the conflict in the Far East continued beyond August 1945, doubtless many more Allied and Japanese lives would have been lost.

As he had been posted to the Far East, George missed the celebrations in Europe that for many service personnel and civilians characterised VE-Day in May 1945. However, together with crew mates aboard HMS Wolfe he did enjoy an extra rum ration in recognition that Nazi Germany had been defeated, and they heard on the wireless about the celebrations in Trafalgar Square. Subsequently, because George was on active service during VJ-Day, there was little scope for him or his crew mates on their submarine depot ship to hold festivities to mark that occasion either.

In the wake of the war in the Far East he remained with HMS Wolfe, but was eventually sent back to India in late 1945. Here he was assigned to a frigate bound for Britain. As an experienced seaman with around 4 years’ service under his belt, he was most welcome because many of the other sailors were newly qualified and this was their first major ocean going voyage.

George arrived back in Portsmouth, where his naval career had started, during 1946. He was soon demobbed and remembers ‘receiving my hat and suit and it, was great to get home.’ As a lad with a strong Methodist background he had joined the Royal Navy, and in the words of pre-war recruiting posters ‘seen the world.’ Like many former servicemen he initially found it hard to settle down in civilian life after the war. However, he later confided that ‘getting married was a big help.’ His wife had served with the Auxiliary Territorial Service, forerunner to the Women’s Royal Army Corps, and they subsequently had two daughters together.

He went back to working for his local Co-operative Store, and ‘it seemed as if nothing had happened, as if I had never been away.’ Eventually he rose to become chief cashier at their head offices in Newgate Street, Newcastle upon Tyne. Then in 1970 with the North Eastern Co-op undergoing a reorganisation, he was offered the position of manager at the North Shields branch. This would have entailed ‘replacing a young fellow with only one kidney who was going to be sacked.’ As George put it ‘I wasn’t going to take a sick man’s job’ and consequently he was made redundant.

While looking for employment he was fortunately able to be interviewed by staff at Fenwick, a large family owned department store department store in Newcastle upon Tyne, for the post of finance manager. Despite technically being overage, he was accepted and stayed with them until he reached retirement. However, he was privileged to be able to continue working for them as a consultant for another five years.

Reflecting on his wartime experiences, George felt that the navy had given him confidence, although he had always been good at dealing with people. He was not bitter that the war had effectively claimed his teenage years, and remained grateful that he never experienced nightmares about the war or suffered serious injury. He remains proud to have served as a member of the wartime or Churchill’s navy, and is an active member in his local branch of the Royal British Legion. In addition to his wartime campaign medals for service in the Mediterranean, Normandy, and Far East, George was pleased to be allowed to wear the Malta George Cross 50th Anniversary Commemorative Medal in recognition of his role aboard LST 8 during Malta convoys in 1943.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Oral History Recording: George Henderson interviewed by James Goulty, 23/1/15.

George Henderson, Draft to LST-8 Private Log of Places Visited in America and Mediterranean Area, Wednesday 17 February 1943-Saturday 22 April 1944.

George Henderson, Wartime Photo Album (especially covering service in the Far East 1944-1945).

George Henderson broadcast on BBC Radio Newcastle, 8 May 2015 to mark 70th Anniversary of VE-Day.

Durham County Record Office: D/DLI 7/273/71, Booklet: 21st (British) Army Group in the Campaign in North West Europe, 1944-1945, Lecture by Field Marshal Montgomery, Royal United Services Institute (London, October 1945).

Books/Chapters

Blackwell, Ian Battleground Europe: Anzio (Pen & Sword, 2006)

D’Este, Carlo Bitter Victory: The Battle for Sicily 1943 (Fontana, 1989)

Grove, Eric J. ‘A Service Vindicated 1939-1946’ in The Oxford Illustrated History of the Royal Navy, pp. 349-380 (Oxford University Press, 1995)

Lavery, Brian Hostilities Only: Training the Wartime Royal Navy (National Maritime Museum, 2004)

Churchill’s Navy: The Ships, Men and Organisation 1939-1945 (Conway, 2006)

Lenton, H. T. & Colledge, J. J. Warships of World War II (Ian Allan, 1980)

Lovegrove, Peter Not Least in the Crusade: A Short History of the Royal Army Medical Corps (Gale & Polden, 1951)

Man, John The Penguin Atlas of D-Day and the Normandy Campaign (Penguin, 1994)

Parkinson, Roger Encyclopaedia of Modern War (Paladin Boks, 1979)

Powdrill, Ernest In the Face of the Enemy (Pen & Sword, 2008)

Tute, Warren, Costello, John & Hughes, Terry D-Day (Pan Books, 1975)

Rogers, H. C. B. Colonel Troopships and their History (Seeley Service & Co. Ltd, 1963)

Webology

www.Wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS-LST-8

Naval Eyewitnesses is available to order here.