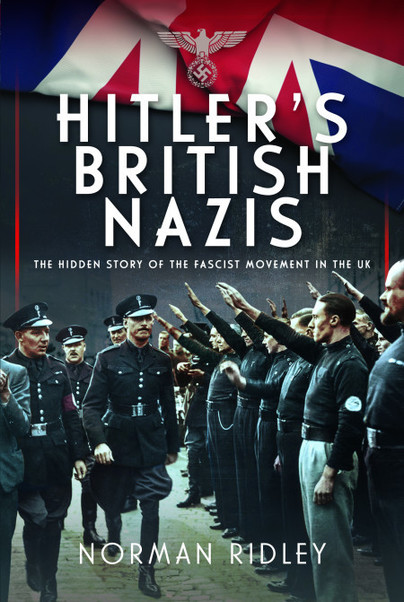

Author Guest Post: Norman Ridley

British Legion chairman Francis Fetherston-Godley visits Dachau

Despite warnings from Permanent Under-Secretary of State, Robert Vansittart that the Nazis would use them for propaganda, on 14 July 1935, a high-ranking delegation from the British Legion led by its chairman Francis Fetherston-Godley, arrived in Berlin to be met by Ribbentrop and representatives of three major German veteran’s organisations. A welcoming message called for ‘mutual trust, mutual respect and the firm belief [in] honourable comradeship of the people.

Right from the end of the First World War, veterans on both sides of the conflict had worked towards reconciliation. The British Legion, which had been formed on 15 May 1921 with the stated aim of providing support for members and veterans of the British Armed services, proposed inviting Germans to join in an international organisation but were prevented by opposition from the French and Belgians. The idea was revived in 1933 when the Nazis came to power in Germany as a way of defusing incipient fears of future conflict but events soon showed that the political agenda would not be set by ex-servicemen motivated by memories of the horrors of trench warfare but by a Nazi movement hell-bent on creating a new European landscape on the back of rearmament and military might.

On behalf of the British Legion, Sir John Brown had accepted an invitation from Baron Hans von Redwitz to make an informal visit to Munich. He was disturbed to find that, as part of the delegation, von Redwitz had also extended an invitation to Graham Seton Hutchison, who had been one of the founders of the British Legion, and two others who were all known as zealous ultra-right anti-Semites. Brown privately considered Hutchison to be ‘a second Hitler’ and even von Neurath, the German Foreign Minister, thought him ‘unbalanced’. Brown’s fears were realised when Hutchison, on their arrival in Munich on 28 March 1934, started making distinctly pro-Nazi statements to the German press and considerably heightened Brown’s distress when he laid a wreath at a German War Memorial commemorating Hitler’s abortive 1923 Munich Beerhall Putsch. The delegation was feted by leading Nazis such as Rudolf Hess and Hutchison responded by heaping praise of the Nazi movement which, he said, had many admirers in Britain.

It was Ribbentrop who made the next approach to the British Legion and the Foreign Office in February 1935 by proposing an official visit, an idea that was debated at the British Legion annual conference in June. It was addressed by Edward, Prince of Wales who supported the visit saying that ‘representative members of the Legion’ were the ideal people to ‘stretch forth the hand of friendship to the Germans.’ Neither the Palace nor the Foreign Office was pleased by Edward’s intervention but, writing in The Times, Ribbentrop was effusive in his praise of a move that supported government endeavours ‘definitely to establish peace and cooperation in Europe.’ The Foreign Office warned the British Legion that they were deluded in thinking that there existed an equivalent organisation in Germany outside Nazi control.

The delegation was astounded to find that a meeting had been arranged with Hitler, himself , at the Chancellery on the day after their arrival. They talked for two hours exchanging memories of the war in which they had all taken part. This had a profound effect on the visitors but Hitler’s translator, Paul Schmidt, noticed that over the following days, their attitude changed to one more critical of what they found. Ribbentrop then met them and spoke of ‘international reconciliation and a spirit of comradeship that would bring the two nations together but the sense of camaraderie was crumbling and took a sudden downturn when the delegation laid a wreath at the Munich War Memorial, which was fine, but then they were asked to lay another wreath at the Beerhall Putsch Memorial as well. They declined on the grounds that such a gesture was too political and not in keeping with the spirit of their mission.

The delegation went on to visit a Hitler Youth holiday camp before being received at the home of the Aviation Minister Hermann Göring. Some days later, they were treated to a guided tour of the Dachau concentration camp. On returning to England Fetherston-Godley, described the camp’s pleasing appearance with trees, shrubs and flowers separating the dormitories but were dismayed by the ‘low types of humanity’ who were incarcerated there. Other members later spoke of the camp’s ambition to ‘reform [miscreants] by healthy exercise, good food, and work.’ They had been reliably informed that the whole staff were out solely to help the inmates ‘make the best of themselves.’

Order your copy of Hitler’s British Nazis here.