Five Things to Know … about the Confederation of the Rhine armies in 1813

Author guest post from John H Gill.

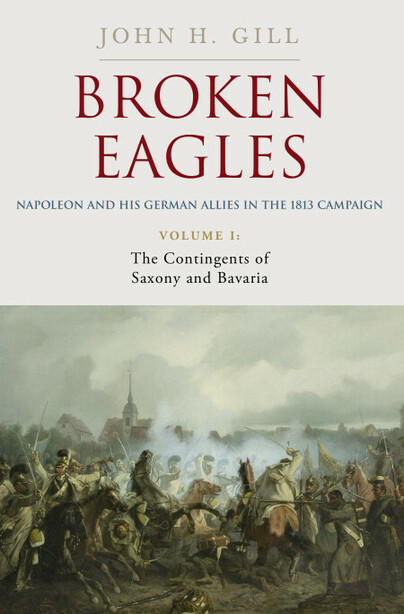

Five Things to Know … about the Confederation of the Rhine armies in 1813. The Confederation of the Rhine (or Rheinbund), a Franco-German military-political alliance created by Napoleon in 1806, came to an end with the French emperor’s defeat at Leipzig in October 1813. During the alliance’s brief existence, its founding treaty required each of the member states to provide a contingent of soldiers to Napoleon’s armies. Men from these various German monarchies thus fought all across the face of Europe: from Vienna to Madrid to Moscow and back to wage their last campaigns as Napoleon’s allies in central Germany. Broken Eagles thus tells the story of these armies in the Rheinbund’s final year.

1. The Rheinbund states contributed more than 90,000 men to Napoleon’s Grande Armée in 1813. Contingent sizes ranged from the 25,000 and 20,000 owed by the Kingdoms of Westphalia and Saxony respectively through the middling, such as the Kingdom of Württemberg’s 12,000 men, to the minute numbers required of microstates like the tiny Principality of Schaumburg-Lippe that was required to provide 150 soldiers. Almost all the states met their treaty obligations in terms of numbers of troops supplied and several, notably the Grand Duchies of Hesse-Darmstadt and Würzburg, went well beyond the Rheinbund’s stipulations.

2. Confederation contingents were present at all the major battles of 1813 and many of the numerous sieges that year. They played significant roles in many engagements, such as the Württemberg division leading the main attack against the enemy centre at the Battle of Bautzen (20–21 May), and they often garnered earnest praise from Napoleon and his generals as the Saxon heavy cavalry did at Dresden (26–27 August). Other contingents in other situations, however, performed abysmally, their record characterised by desertion and defeat. Green Westphalian infantry and a newly minted regiment from the Thuringian microstates routed at Hagelberg (27 August), for example, and these same units proved so unreliable as elements of the Magdeburg garrison that the commandant released them rather than feed men who were more prone to desert than to fight.

3. Many contingents fought on as French allies even after Napoleon’s disaster at Leipzig in October. German troops had proven to be some of the most stalwart elements of the Danzig garrison, for example, and remained loyal until they had received official word from their home governments when they marched out of the fortress with honour and acclaim from their French commanders. The same was true for most of the major contingents in the field with the Grande Armée.

4. Some troops did defect to the enemy, but the scale of defection needs to be placed in perspective. Best known is the defection of the Saxon division on 18 October in the middle of the Battle of Leipzig. Though considered infamous, this action certainly did not cause Napoleon to lose the battle (as many French claimed) as the Saxons represented less than 4,000 men out of an army of nearly 200,000. Furthermore, adding up all unit defections, the total number of soldiers involved comes to approximately 7,000, or only perhaps ten percent of all Rheinbund troops present under arms at the height of the autumn campaign. In contrast, the contingents from Grand Duchies of Baden and Hesse-Darmstadt (nearly 8,000 total) steadfastly refused to change sides and insisted on formally surrendering so as not to violate their oaths to their respective sovereigns.

5. The Confederation of the Rhine collapsed in 1813, a political consequence of military defeat. Although most of the member states hastened to switch sides after Leipzig, Bavaria joined Napoleon’s enemies before that great battle. Indeed, it most senior general, the ambitious Karl Philip Graf von Wrede, led a combined Austro-Bavarian army to intercept the retreating French. Along the way, he threatened several of Bavaria’s former Rheinbund allies with invasion, intimidating them into deserting Napoleon. The postwar fates of the Rheinbund’s members varied. Newly established entities, such as the Kingdom of Westphalia, erected by Napoleon in 1807, dissolved with the emperor’s defeat, their constituent parts going to former rulers or to Prussia. By aligning themselves with the Coalition opposing Napoleon and by committing their armies to war against France in a timely fashion, however, the majority of the Confederation monarchies were able to preserve their titles and most of their lands and subjects. As a result, much of post–1813 Germany bore a strong resemblance to the Germany Napoleon had created during the years of his dominance.

Order your copy here.