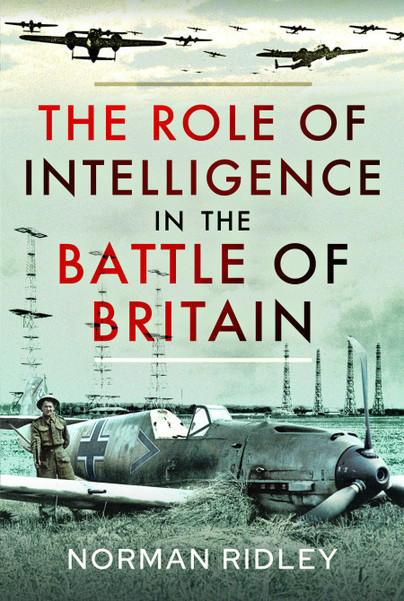

Norman Ridley: The Role of Intelligence in the Battle of Britain

Survival at Sea

During the Summer of 1940 the North Sea and English Channel proved to be a significant complicating factor in the operations of both the RAF and the Luftwaffe. For fighter pilots on both sides the prospect of losing their aircraft and having to bale out over water was a constant nagging worry apart from the stress of the actual combat itself. After the first few weeks of combat when engagements were increasingly taking place over the southern counties of England, Air Vice-Marshall Park had ordered his pilots to avoid chasing enemy aircraft out over the water but the Luftwaffe pilots had to cross water twice, the second time possibly in a damaged aircraft or, more likely, one with its red fuel warning light glowing ominously. At least they had an efficient air-sea rescue service with their Heinkel He59 Seenotdienst float planes and Schnellboot fast patrol craft which is a whole lot more than the RAF pilots could count on. More than fifty Luftwaffe Bf109 fighter pilots were rescued in this way and also a small number of British pilots owed their lives to German rescue craft. The British fighter pilots were actually ordered to attack any He59 aircraft they encountered, in the air or on the water, whether or not they were sporting a red cross. Bombers on both sides also had to cross the water twice on their missions. The following accounts tell of the lucky ones, from both sides, whose aircraft were lost over the sea and who survived to tell the tale.

At 11 o clock on the morning of August 15th 1940, the sky over the Norwegian airfield of Stavanger began to fill as 60 Heinkel He111H bombers of the 1st and 3rd Gruppen of KG 26, the Luftwaffe Kampfgechwader ‘Löwen’, met up in close formation. They were about to embark on a mission, postponed from the previous day, to cross over 400 miles of the North Sea and attack airfields in Northern England. This would take them way beyond the range of the Messerschmidt Bf109E fighters which would normally fly with them as a defensive shield but that was not a major concern since their intelligence was that their targets were now undefended with all their protective cover of fighter squadrons having been hastily redeployed to the Home Counties in a last-ditch defence against the great Luftwaffe offensive of ‘Adlerangriff’. Anticipating a ‘soft’ target, Generalobertst Stumpff sent the twin-engine Messerschmidt Bf110 ‘Zerstorer’ heavy fighters of ZG77, as escort. These were more heavily armed than the Bf109s but lacked their speed and manoeuvrability. Even these had been stripped of one of their machine-gun turrets to allow for the weight of auxiliary fuel tanks required for the long journey. Morale amongst the crews was high as they embarked on their first major offensive of the Battle of Britain.

Hoping to ‘shoot fish in a barrel’ Stumpff also dispatched bombers from Aalborg, in Denmark, and Grove, in Germany, to simultaneously attack airfields in Yorkshire used by RAF Bomber Command in a bid to ease the growing damage done to German morale by nightly bombing raids over their home turf. The stage was set for what Stumpff expected to be a turning point in the whole offensive against Britain whereby he would open up a second front and apply the second arm of a pincer that would close in and apply a crushing grip on the city of London.

Luftwaffe Chief, Reichsmarschall Göring was quick to accept the claims of his pilots, exaggerated as were those of the RAF, confirming the large numbers of Spitfires and Hurricanes shot down since the beginning of July. His Intelligence chief ‘Beppo’ Schmid had also convinced him that Fighter Command was down to its last few aircraft. The unfortunate crews of KG 26 and ZG77, however, were soon to discover that this was one of a number of catastrophic miscalculations made by the Luftwaffe throughout the Battle. Fighter Command still had four fully manned and operational aerodromes in the area; Drem, just east of Edinburgh, was home to Hurricanes of 605 Squadron; Acklington in Northumberland housed Spitfires of 72 Squadron and Hurricanes of 79 Squadron; Usworth just east of Sunderland, Hurricanes of 607 Squadron and Catterick in North Yorkshire Spitfires of 41 Squadron. For all of these squadrons it was also to be their first real experience of combat in the Battle of Britain although all except 72 Squadron had only recently been heavily involved in the Battle of France and the Dunkirk evacuation.

Just after noon, British radar picked up ‘tracks’ of hostile aircraft moving south-west about 100 miles off the Firth of Forth. The 60 He111s were flying at 18,000ft with 20 Bf110s just behind and a little above them. Having been scrambled to investigate the ‘track’ 11 Spitfires of 72 Squadron approached at 22,000 ft and immediately attacked from above and astern. The bomber crews were first catapulted into a state of high anxiety by interference of their radio traffic and then were taken completely by surprise as the Spitfires attacked taking down, without any loss to themselves, a number of their Bf110 escorts, now vulnerable due to their rear gunners having been sacrificed for extra fuel load. Using the powerful ‘De Wilde’ explosive ammunition, 72 Squadron inflicted serious damage on the 110s but there was only so much a the relatively small force of Spitfires could do against the whole flotilla and ammunition soon ran out leaving the He111s to advance towards their targets.

The bombers crossed the coast near Acklington with the remaining Bf110s several miles behind. Hurricanes of 79 Squadron, protecting their base airfield tackled the straggling Bf110s and again inflicted serious damage turning them back as the main bomber force, somewhat losing its bearings due to cloud cover, turned south towards the Tyne. A break in the cloud revealed Sunderland below and the bombers released their loads, having been instructed to hit harbours as secondary targets in the event of them not finding the airfields. 41 Squadron’s Spitfires now took over as 79 returned to base to re-arm and re-fuel. The bombers were dispersed over a wide area, one eventually being shot down over Barnard Castle.

In the midst of the carnage wreaked on Luftwaffe crews, one story of endurance and survival stands out. Pilot Oberleutnant Hermann Riedel had just unloaded his bombs over the Wear shipyards at Sunderland when his He111H-4 of 9th Staffel of KG 26 was set upon and hit by 2 Spitfires of 41 Squadron flown by Pilot Officer Oliver Morrogh-Ryan and Flight Lieutenant Edgar Ryder. Riedel’s starboard engine was set on fire, but the Spitfires ran out of ammunition and had to call off the attack, one even waving to Riedel as he flew alongside and away. The damaged aircraft slipped into a cloudbank and headed east managing to send out a distress signal despite almost total instrument failure. At just above wave height, the damaged engine gave out and the Heinkel was forced to ditch in what was quite a choppy, cold and uninviting North Sea. Riedel and his crew; Feldwebel Willi Scholl, Oberfeldwebels Kalle Müller and Paul Süssenbach took to their life raft before the aircraft sank. Riedel salvaged his camera and recorded the following ordeal for posterity.

As night fell, the men became despondent but just before dark they heard an aircraft and set off flares. The aircraft turned out to be a Heinkel He59 of German air-sea rescue which, despite the heavy seas, managed to land and the stricken crew were unceremoniously hauled on board. Having landed, the He59 now had to take off which proved almost impossible but with engines gunning at full throttle and the waves crashing into the flimsy body, it eventually made it into the air. Riedel dozed and woke to see the He59 radio operator signalling with a lamp to what he thought was a German aircraft, but which turned out to be an RAF Lockhead Hudson of Coastal Command’s 206 Squadron.

For the second time that day, Riedel and his crew were strafed by British bullets and forced to ditch in the North Sea, the salt of which they had hoped never to taste again. They were strafed again in the water then the Hudson left apparently satisfied that the Heinkel would never fly again. During the attack, one of the Heinkel crew was hit and severely wounded. Riedel suddenly realised that his crew had been availing themselves of the rum rations salvaged from the He111 and were quite inebriated. As the night wore on, the weather worsened. Half the airmen took to a life raft while the others stayed with the, now, madly lurching aircraft. The running sea took the liferaft, with most of the provisions, away and frantic paddling by the occupants failed to return it to the aircraft as it slowly drifted out of sight. Reidel and two others, wet and freezing cold, remained with the aircraft.

At around noon on the following day, in the vastness of the stormy North Sea, the men were again spotted by German air-sea rescue; this time a Dornier 24. Using hand signals, Riedel managed to instruct the aircraft to go and search for the dinghy which it eventually found but, on landing to pick up the occupants, suffered catastrophic structural damage and could not get airborne again.

Meanwhile, Riedel still with the He59, together with his two companions endured another uncomfortable night buffeted by the waves but next day were spotted by a German minesweeper and taken on board. The ship had spotted them a day earlier but had been unwilling to approach as they were floating through a minefield. Soon the minesweeper had spotted the liferaft and the rest of the crews was taken to Norderney off the Dutch coast. Riedel, undaunted was in the air again the next day piloting a borrowed He111 and taking his crew safely back to the KG 26 base at Schwerin in Germany.

By any account the operation was a disaster for Stumpff and his crews. No military targets were hit and the losses suffered by KG 26 amounted to 8 He111s destroyed with 21 crew dead and 5 more being taken POW. A further 13 crew were rescued by German naval vessels. 6 Bf110s were destroyed with 10 crew killed and 2 made POW. RAF casualties were 4 aircraft damaged with 1 pilot seriously wounded.

Order your copy here.