Remembering the Lisbon Maru: VJ-Day, New Films, and the Forgotten War Crime of 1942

Author guest post from Richard Graham.

The recent marking of the 80th anniversary of VJ-Day appears to have prompted print and broadcasting media interest in a deeply tragic event in the Far East War of 1941-45, namely the sinking of the Lisbon Maru, one of that war’s most egregious, yet least known, war crimes. The VJ-Day anniversary may also have helped to create a national mood more favourable and receptive to remembrance of such grim events. Special curiosity about this tragedy that took place in the East China Sea in October 1942 has been aroused by the recent release of two films, the first an intensely moving documentary, The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru, the second a melodramatic feature film, Dongji Rescue.

My book, At the Emperor’s Pleasure, is a special, perhaps even unique, fit into this background in that it provides the before-and-after context that is crucial to understanding one of the Second World War’s most tragic incidents, as seen through the eyes of those who experienced and survived it.

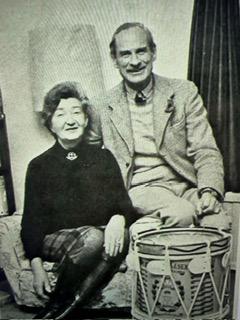

When I was commissioned into the ‘Diehards’, Major General Christopher Man was Colonel of the Regiment. As a young captain, he had survived the savage battle for Hong Kong, the sinking of the Lisbon Maru and then three years of forced labour as a POW in Japan. His wife, Topsy, was herself captured by the Japanese and endured four years of inhumane treatment as an internee in Hong Kong. Separated throughout their captivity, neither knew the other was still alive. Topsy discovered that Christopher had been on the Lisbon Maru but only learned that he had survived when they met by chance three years later in Colombo as they made their separate ways home.

also the 40th anniversary of their chance reunion in Colombo.

My book is their story, but not theirs alone. It recalls the rescue by Chinese fishermen of several hundred survivors of the Lisbon Maru as experienced by the last surviving member of that gallant band of rescuers, Lin Agen. Amongst the many threads that run through the book, it is the role of the Chinese fishermen in saving the lives of British POWs that is especially topical and thought-provoking in light of the mutual suspicion which characterises relations between the United Kingdom and China some eight decades later.

It was of course a wholly different world then. When the British garrison surrendered to the Japanese on Christmas Day 1941, China had already endured four years of brutal military occupation by its East-Asian neighbour. For the Chinese and the British, it was a clear case of “my enemy’s enemy is my friend”. The outlying islands of the Zhoushan peninsula, where generations of Lin Agen’s family had fished for their living, were within reach of the Japanese reign of terror and had felt the heavy hand of China’s ruthless occupier.

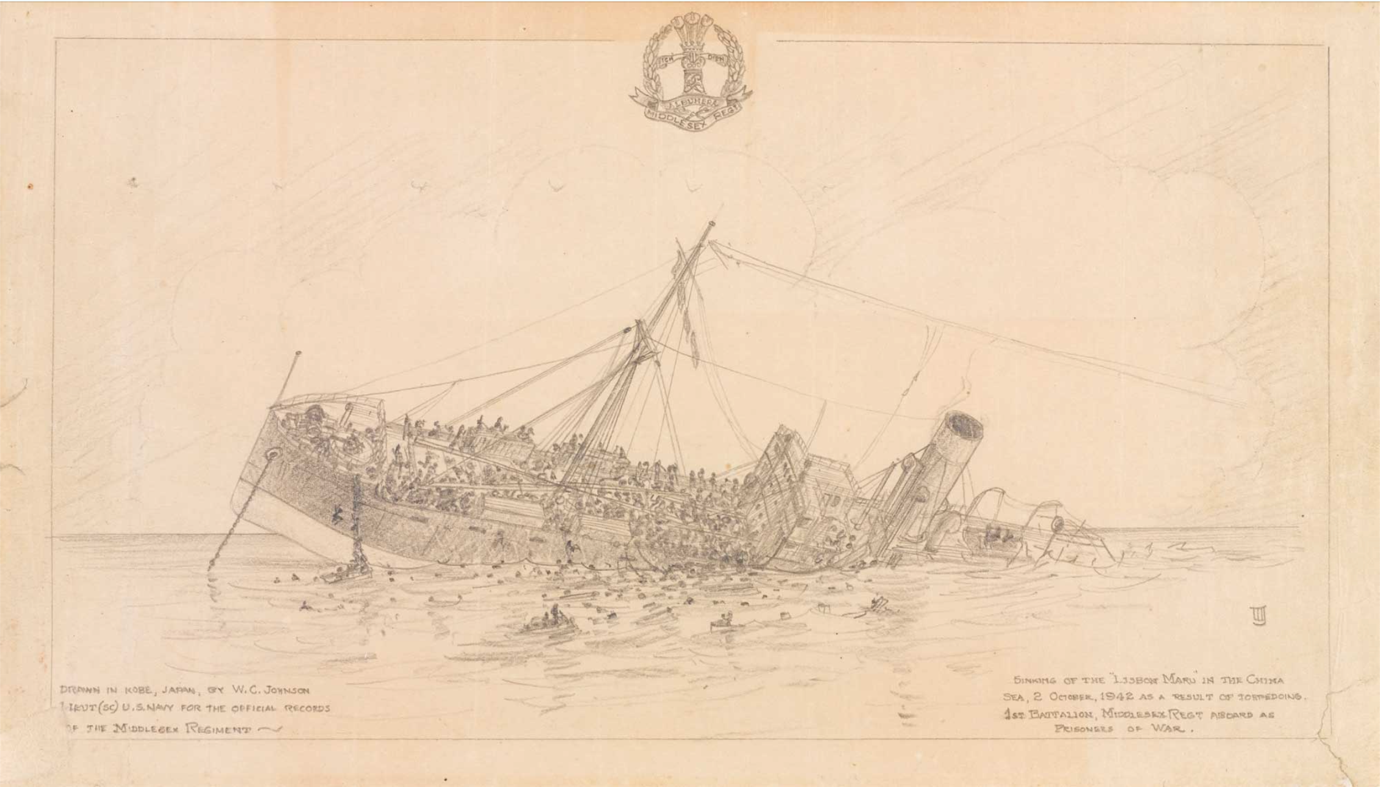

It was around mid-morning of 1 October 1942 when the young Lin Agen and his father heard an explosion from a few miles further out to sea from where they were fishing off the east coast of their home island, Qingbang. The sound of distant gunfire followed and within minutes a Japanese warplane passed over them, flying low and headed towards the source of the commotion. Just over the horizon from their sampan, the Lisbon Maru had been struck by one of four torpedoes fired by the American submarine, the USS Grouper, and had shuddered to a stop. The Lisbon Maru had sailed from Hong Kong four days ago, bound for the Japanese port of Moji. On board the 7,000-ton, converted and armed troopship were several hundred Japanese troops and 1,816 British prisoners of war who were destined to labour in Japan’s mines, ports and factories. The POWs were already in a bad shape after nine months of harsh captivity in Hong Kong: they were malnourished and only a few had escaped debilitating disease of one sort or another; and to make matters worse, they had all spent most of the voyage shut down in the ship’s three cargo holds, deprived of space, fresh air, light and adequate sanitation. The Japanese reaction to the attack was to panic: the ships guns, one fore and one aft, began firing at an unseen enemy while the guards forced all prisoners into the holds before covering and battening down the hatches. Lin Agen and his father could see none of this, but the sound of war was clear enough; instinct, fed by previous experience, told them to forget fishing for the day.

The Lisbon Maru took 24 hours to sink. During that time, the Japanese soldiers and crew were transferred onto rescue ships, leaving only a handful of guards on board with a suicidal mission to ensure that the trapped prisoners went down with the ship. With only minutes to spare and the stern deck already under water, prisoners in Christopher’s hold managed to break through the hatch cover, overpower the guards and open the remaining hatches, but too late to save most of those trapped in the stern hold. From the small flotilla of ships now at the scene, rescued Japanese soldiers shot at prisoners as they emerged on deck. Those who had made it into the sea and were being carried by the current towards the distant Zhoushan islands were also shot at and had to avoid attempts to run them down by Japanese patrol boats. The Japanese intention was clear: none should survive to tell the tale. The fishermen of Qingbang and its neighbouring islands had other ideas. Lin Agen was amongst those who had gathered on Qingbang’s eastern clifftops after sunrise on 2 October. It was difficult to make out the distant scene, but once swimmers and flotsam drifted within sight, their instincts as men of the sea took over. Men needed saving at sea. They had no idea who they were, but it was their code as fishermen to rescue them whoever they were. And they did. At great risk to themselves, they launched their sampans and hauled over 300 survivors from the sea. Observing this intervention, the Japanese stopped firing at survivors and began to pick them up themselves.

A total of 828 British POWs perished that day. A further 200 or so, many of whom had spent several hours in the sea, never recovered from their ordeal and lived for only a few days and weeks more. Islanders fed and sheltered survivors overnight but the next day, Japanese marines landed in force and rounded them up, to be transported in the holds of another freighter to Japan where their future lives as forced labourers would begin.

Like his fellow survivors, Christopher Man never forgot the kindness and courage of the Zhoushan fishermen and their families. When Japan surrendered on 15 August 1945, his life changed in an instant from surviving captivity to helping the authorities maintain law and order in a chaos-ridden Kobe. In that role, it was fitting that one of his first interventions was to rescue from their guards a band of starving and still-endangered Chinese prisoners. Once back home in England, Christopher raised funds from fellow survivors and was present when the proceeds were presented to representatives of Qingbang by the governor of Hong Kong.

The Lisbon Maru incident and the courageous role played by Chinese fishermen in it, remained little known both in the United Kingdom and in China until recently. Fittingly, both nations at last host appropriate memorials. Christopher Man and his fellow survivors and the fishermen of Zhoushan would be pleased.

Order your copy here.