The record of an exciting life – Lieut. Frank Abbott ends up in the Zulu War

Author guest post from Peter Duckers.

In the mid-1960s, two events kick-started what has turned out to be abiding interest in a colonial “small war” of 1879. The two events were the appearance of the popular film “Zulu” in 1964, followed next year by the publication of “The Washing of the Spears”, the first modern, detailed history of ‘the rise and fall of the Zulu nation’. Its author, the American naval officer, Donald R. Morris, produced an immensely readable history of the Zulu nation and its rise as a military power under king Shaka, culminating in a dramatic account of its ‘fall’ following defeat by the British in 1879. Although much of the detail of Morris’s account has been superseded by modern scholarship it remains an iconic work on the history of Zululand and a “must read” for anyone interested in the campaign of 1879.

As a result of the popular and academic interest aroused in this previously neglected colonial campaign, there has been a huge outpouring of research and publications, from popular books to serious, academic works. It is a fact that the Zulu War – despite its comparatively small scale – has produced more in terms of the written word than just about any other campaign in Nineteenth century British military history.

The appearance of new information on the war – increasingly a rare occurrence as archives of all kind in Britain and South Africa are mined for further detail – becomes a matter of considerable interest. The appearance recently of the surviving journals and letters of a young naval officer who served in the campaign is therefore cause for comment.

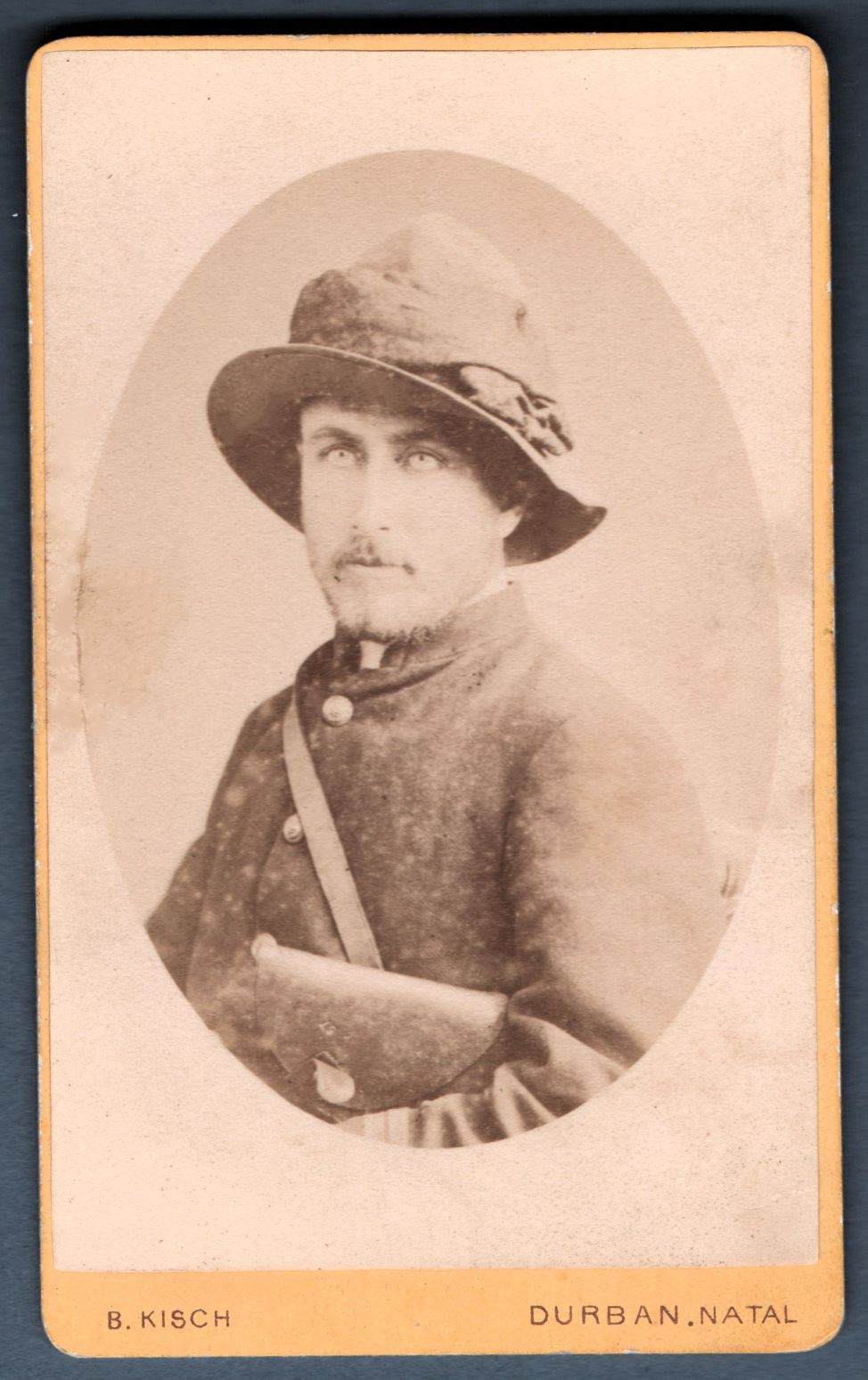

Thomas Francis Abbott – known as ‘Frank’ – had a short but exciting naval career. The son of a naval officer, Jonas Abbott, who rose to the rank of admiral, Frank Abbott followed his father into the Royal Navy. One sometimes forgets the huge range of the Royal Navy’s worldwide commit-ments in the late Nineteenth century. As a mere teenager Abbott found himself on long voyages to exotic locations – through the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean and in the Far East to Thailand, Hong Kong and China. His letters home and detailed journals reflect his fascination with the places he visited but we should not forget that this was not mere tourism; Abbott had a demanding job as a serving officer and his journals reflect the daily routines of running an ‘efficient’ warship as it cruised the long international trade routes which the Royal Navy needed to protect.

Abbott found himself pitched into a real crisis in 1875. Despite his youth – he was only 21 – he was appointed to command the escort of Britain’s new ‘resident’ in Perak, James Birch, based at Banda Bahru on the Perak River. When Birch was murdered in November 1875 and a local uprising began, Abbott was advised to abandon the residency and escape to Penang with the escort and staff. Rejecting the suggestion, considering that it would weaken Britain’s authority in the region and abandon people who were sympathetic to the British presence, Abbott put the residency into a state of defence and with only four sailors, 50 Indian police and a few civilians, prepared to repel an attack. The show of defiance worked; the armed mobs heading for Banda Bahru stopped short at the sight of the stockade and its defenders and held back. This gave time for the authorities in Penang to send out a relief force and as a result, two assaults were made on ‘rebel’ villages, with Abbott taking a prominent part in both. Unsurprisingly, for Abbott received many commendations from the naval and civil authorities and, apart from ‘mentions in dispatches’, was immediately promoted to Lieutenant – which greatly pleased him!

In 1876, Abbott was posted to the magnificent new frigate, HMS Shah as it set off on a long voyage across the Atlantic, around Cape Horn and along the west coast of the Americas to join Britain’s Pacific Squadron. Over the next years, Shah would visit major ports in the Americas, especially where Britain maintained naval facilities (such as Valparaiso), visit islands in the Pacific – like Pitcairn – and re-visit Esquimault in Canada, then just being developed as a base in the northern Pacific.

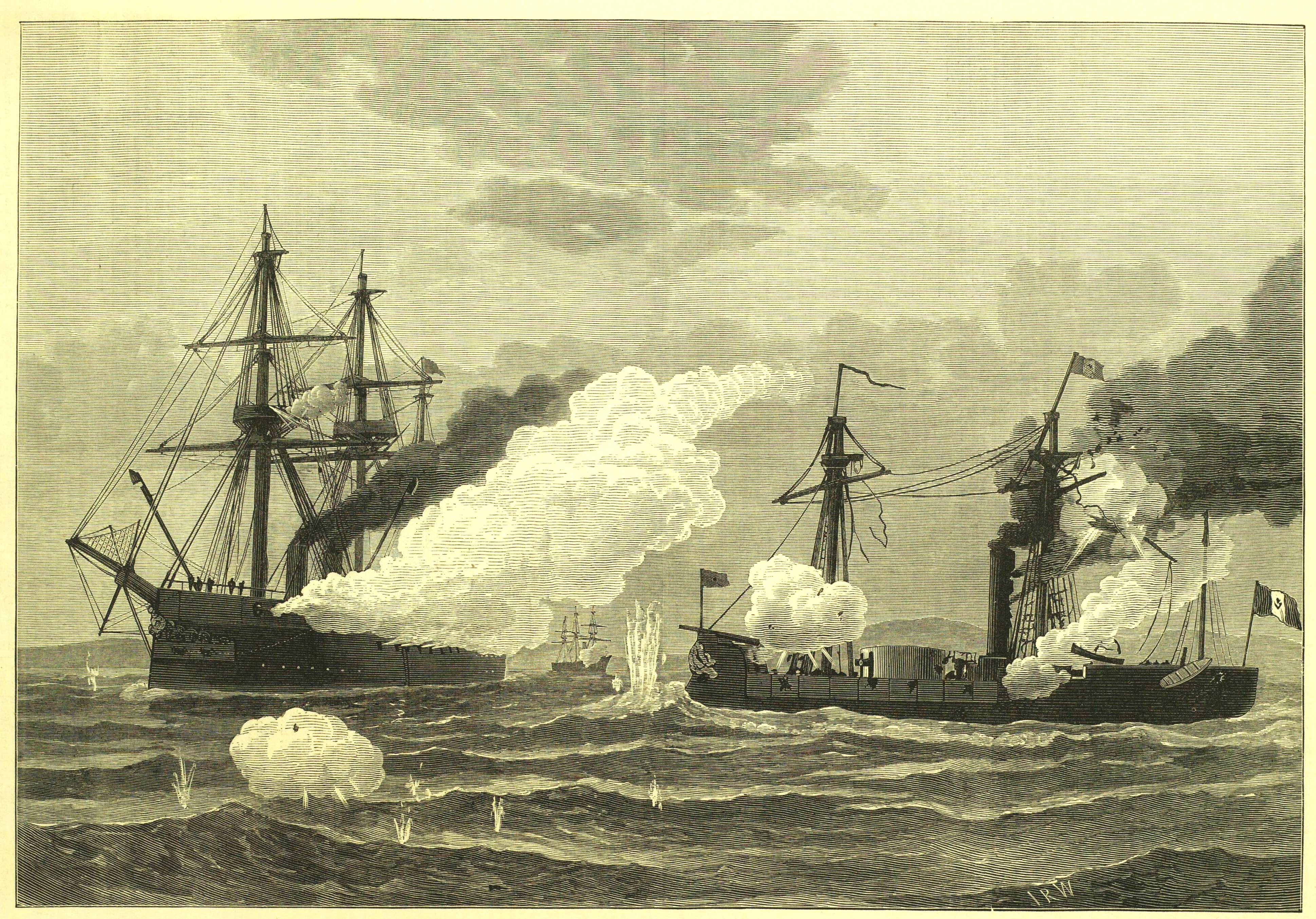

It was during this tour that Shah famously engaged, in a rare ‘ship to ship’ action, the Peruvian ironclad, Huáscar, in ‘the battle of Pacocha’ on 29 May 1877. This saw the first use of torpedoes in a naval action, when Shah launched one at the Peruvian ship. It failed to strike, since the enemy vessel managed to turn aside, and a later attempt to use two more torpedoes – with Abbott fully involved with the torpedo crew – was called off. Nevertheless, Huáscar surrendered the same day.

In December 1878 Shah began its return journey to Britain around Cape Horn. Whilst at St. Helena, they heard of the disaster in South Africa – the destruction of a British army at Isandlwana in Zululand on 22 January 1879. The Shah’s captain, Richard Bradshaw, took a brave and decisive decision; despite the fact that the ship had already been away for three years, he embarked just about the whole garrison of St. Helena, infantry and artillery, and headed for the Cape. The sight of this huge warship anchoring off Durban brought great relief to the colony – and along with over 300 troops and guns, Bradshaw landed nearly 400 men from the Shah, providing a significant addition to the forces in the colony.

Abbott was clearly excited to be landed with the naval brigade, as his enthusiastic letters and journal entries show, but he did not immediately take part in the renewed campaign. Instead, he was appointed to manage the pontoons crossing the Thukela, with the vital task of ferrying thousands of troops and huge quantities of stores, transport and munitions across the river frontier between Zululand and Natal. Abbott was officially commended for what was an exceptionally arduous job and afterwards achieved his wish of going forward with the renewed invasion, serving with the naval brigade in the advance along the coast to establish a new supply depot at Port Durnford.

From 1880-82, Abbott served in the Mediterranean, initially aboard the flagship Alexandra and then on HMS Minotaur. In the latter, he again served ashore as part of the landing parties which secured Alexandria during Britain’s invasion of Egypt in August 1882.

In September 1884, Abbott achieved his long-held ambition when he was appointed to the Royal Yacht, Victoria and Albert. Such a posting could be career-changing; it gave officers the chance to meet and be known by ‘the great and good’, not only the monarch and the royal family itself, but also the upper echelons of society and naval command.

However, Abbott’s busy career – and hopes of advancement – were suddenly dashed. He had suffered recently from headaches and debilitation, initially put down as ‘brain fever’ or the effects of service in the tropics. Treatment at Haslar hospital did no good and to the immense distress of his family, his colleagues on the Royal Yacht and of the Queen and royal family itself, Frank Abbott died suddenly of a brain tumour whilst in his father’s house in Ryde on 30 May 1886 at the age of only 32.

Abbott’s surviving letters and journals, selections of which feature in HMS Shah in the Zulu War, reflect the range of his varied experiences in the Victorian navy and clearly demonstrate his efficiency and dedication as a young officer. Though in the end he did not live to fulfil his undoubted promise, these writings at least preserve the memory of a significant and interesting naval career.

Order your copy here.