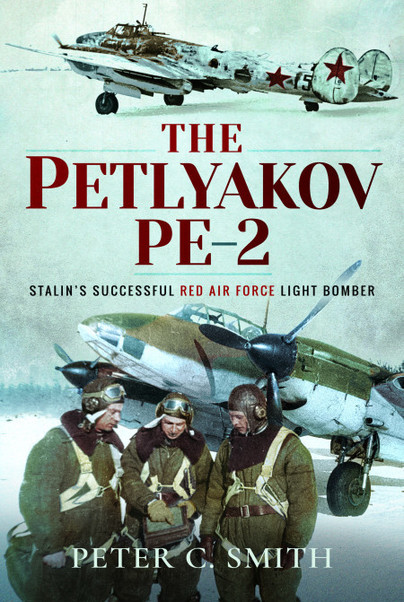

Author Guest Post: Peter Smith

“NONE SO BLIND” – the RAF attitude to dive-bombing.

One aspect of the Petlyakov Pe-2 story that is very revealing was the attitude taken by the RAF to detailed reports of both the speed and accuracy of the Soviet Peshka dive-bomber. Although it had been the British that first carried out successful dive-bombing in combat, with Second Lieutenant William Henry Brown of 84 Squadron, flying a Bristol SE5a biplane, making a precision attack against a German ammunition barge on a canal near Bernot, Haute-de-France, Aisne, on 14th March 1918, and destroyed it. Despite success of this mission, termed “Special Mission (Low bombing attack”), the RAF had, during the interwar years 1920-1939, vehemently opposed any introduction of dive-bombers into service. More, having control over all aircraft production during that period, they had retarded the introduction of the dive-bomber into the Royal Navy, which itself was eager to embrace it in the same manner as had been done by their major naval contemporaries, the United States Navy and Marines and the Imperial Japanese Navy. Both the latter two services had not only adopted this method as the most accurate form of attack against shipping targets but had avidly developed this form of attack as a major specialist instrument. The Royal Navy had been eager to follow them, but received little or no encouragement from their sister service, with the result that, the tardily introduced Blackburn Skua was expected not only to conduct the dive-bombing mission, but also to conduct the main fighter defence of the fleet as well. This despite the fact that post-war naval exercises had, by 1928, shown that the most desirable target for dive-bombers were the aircraft carriers of an enemy fleet.

Experiments conducted at the RAE Armament Experimental Station at Orfordness early in 1918 with both the SE5a and Sopwith Camel delivered the verdict that such a method of bomb delivery was “quite unsafe” and the results expected were “not worth the expenditure in machine and trained pilots.” From this attitude the official RAF line was formulated and was hardly to budge for the next thirty years. Not surprisingly they adopted Italian General Giulio Douhet’s doctrine that tactical air support for the Army was “useless, superfluous and harmful.” Not only was dive-bombing deemed unsafe, there was also the underlying factor that the RAF had been formed “on the hoof” from the Army Royal Flying Corps and the Navy Naval Air Service, and became fiercely protective of its independence from their two parental services. Anything that smacked of “subservience” to either the Army or Navy was deemed irrelevant and the concept quickly became the established RAF mantra that only the heavy bomber could win any future war, and more, it could do so unaided! When biplanes began to be replaced in the world’s air services by the monoplane and speed rose, the RAF was also firm in its conviction that such developments meant that dive-bombing was impossible to carry out. Having rejected such proposed dive-bomber designs as the Hawker PV4 biplane of 1934 and later the superb Hawker Henley monoplane the RAF settled for the low-level approach as typified by the Fairey Battle, and that method saw them shot out of the skies en mass over France in 1940 by German anti-aircraft guns. One leading RAF figure, Lord [William Sholto] Douglas of Kirtleside was later to bemoan such decisions, writing that he later felt “with the deepest regret” that it would have been better to develop a dive-bomber along the lines of the German Junkers Ju.87 Stuka, “instead of those wretched Battles” The general opinion that held firm sway in the RAF was typified by that of Wing Commander John Colesworth Slessor as early as 1934 in which he averred that “the aeroplane is not a battlefield weapon.” On 10th April 1936 a detailed report stated that “aircraft of clean aerodynamic design will reach too high a velocity to make recovery …safe and certain”, while in September 1938, another Committee report read “That steep dive bombing should not at present be regarded as a requirement for modern RAF aircraft.” It added that “no special dive bombing armament trials are required.” Moreover, as if to obliterate for ever the term from its terminology the very words “dive-bombing” were to be expunged, and that “this type of bombing should in future be termed Losing Height Bombing”.

Thus, when, in 1941, Germany turned upon its former ally who had helped her crush Poland in 1939 and invaded the Soviet Union, and an RAF detachment was despatched to co-operate with Soviet air forces around Murmansk, it was a real eye-opener when the British Hurricane fighters flew combined missions with the Pe-2. Squadron Leader Douglas Fairlie Lapraik, DFC, RAFVR, produced a highly detailed report for the Air Ministry on 11th September 1941 in which he enthused that the Peshka was “one of the most notable aircraft produced in Russia” and was “of a type with no counterpart in the RAF” and that “there is no provision for level bombing.”* There followed an extensive and very detailed report on every aspect of the Peshka’s performance. One RAF Engineering Officer that accompanied the Hurricanes to northern Russia wrote in his report that “The Pe-2 climbed and flew at a rate that astounded our boys considerably. In an operation that lasted as long as an hour they had to go all-out to keep station”.

With both these reports before them two years later the Assistant Chief of the Air Staff was writing on 3rd March 1943 that although, “the Pe-2 is usually employed in dive bombing, that “we have no knowledge of the dive bombing technique they employ in operating the Pe-2, nor has the Pe-2 been popularised as had the Il-2.” He added, “About the Pe-2 we have no information to indicate that its contribution is in any way outstanding.”

Similar amnesia appears when the results of combat operations employing American-built Vultee Vengeance dive-bomber were mentioned. When AHQ Bengal signalled to AHQ India that:- “I cannot exaggerate the importance I attach to the early arrival of Vengeance dive bombers in the command.” He considered that twin-engine Bristol Blenheim and Lockheed Hudson level bombers were “quite unsatisfactory for attacks on ships at sea or in harbour ” , and that, “had dive bombers been available I consider that our object at Akyab on 9th September could have been achieved at less than half the effort”, and that he would “gladly release a Blenheim squadron in exchange”. When he added in April 1943 that, “We have not lost one Vengeance in operations and it has been able to do its job effectively and with impunity” he was quickly warned off by Air Ministry back in Whitehall on 12th June. They told him “Vengeance dive-bomber publicity presents many pitfalls from standpoints of both of security and publicity.” They considered the Vultee to be, “worse, in almost every respect, than the Battle”. However, in fact, the six Vengeance squadrons operating on the Burma Front did not lose a single aircraft to Japanese fighter aircraft in the whole three-year period of combat operations.

Moreover, despite their almost pathological opposition to dive-bombing, the RAF was forced to adopt it in Europe where they had always maintained that it was obsolete and untenable. They did this initially with dive-bombing attacks conducted by specially converted Hawker Typhoon aircraft (known as ‘Bomphoons” ) in France prior to D-Day*and subsequently with the North American Mustang*; and finally, in the winter of 1944/45 against more terrible weapons where only accuracy would count. In order to hit elusive V-2 (code named ‘Big Ben’) launching sites, Operation ‘Big Ben’ was conducted. These V-2 rockets, toting a one-ton warhead, were unstoppable once launched, and they would hit their London targets before you heard them coming, so the only way was to attempt to pre-empt as many of them as was possible. Between 4 December 1944 and 31 March 1945 clipped wing Supermarine Spitfire’ XVIs, converted to carry pair of 250lb bombs, and later a 500lb bomb, were employed as makeshift dive-bombers to seek out and precision attack these targets. Typically, these attacks were delivered by a quartet of Spitfires from a tip over point at 8,000ft altitude with release at 3,000ft in sequence followed by a low-level pull-out. These figures varied widely due in main to the weather conditions in Europe at this period were, of course, poor and so many attacks were forced to be aborted, but dive-bombing was the only precision way of doing anything about them, so the Air Marshalls had to eat their words. But they were given minimum publicity at the time, and since, and although briefly mentioned in my Dive Bombers in Action book, most of the detail and drawings of the bomb arrangements were edited out by the publisher. Thankfully Craig Cabell and Graham A Thomas have finally recorded these missions extensively**, but it is typical that the Air Ministry did not publicise these dive-bombing missions while lauding the mass destruction of German cities as “the war winner”.

* Blackadder, Wing Commander A F , Air Fighting Development Unit, RAF Wittering. Report No. 149 Mustang Dive-Bombing, 10th October 1944. (AIR24/605). Also – National Research Section (ADGB): Dive-Bombing Tactics – Analysis of two Bombphoon Attacks on Ground targets in Northern France, 14 March 1944. (AIR21/1140)

** Operation Big Ben: The Anti-V2 Spitfire Missions 1944-45, Spellmount, 2004.

The Petlyakov Pe-2 is available to order from Pen and Sword Books.