Author Guest Post: Steve Dunn

How the Royal Navy fought to save Estonia and Latvia

The thriving modern republics of Estonia and Latvia emerged from the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and are still threatened by the revanchist policies of the USSR’s successor state. But the fact that they exist at all is in large part due to the Royal Navy and particularly the role it played immediately after the First World War in helping fight off the expansionist ambitions of a post-Armistice Germany and the greed and aggression of the nascent Russian Bolshevik Empire.

For many men in the Royal Navy, the war did not end on 11 November 1918. No sooner had the German fleet been interned at Scapa Flow, than the navy was ordered into the Baltic Sea to hold the ring and protect the fragile embryonic states of an independent Latvia and Estonia.

The Baltic was ablaze with a range of conflicting polities. All along the littoral, a plethora of factions staged a bloody and vicious conflict for control of the region. The Bolshevik Red Army and Navy fought to bring the region under Communist rule; German-Baltic Landwehr were intent on making a new German client state; White Russians were bent on reinstalling a tsarist monarchy (and taking back the Baltic States for their old rulers, the Tsars). Then there were local freedom fighters, at war with all and often with each other; and even the regular German army, forced by the Allies under Article XII of the Armistice to remain in place as a reluctant barrier to communist expansion.

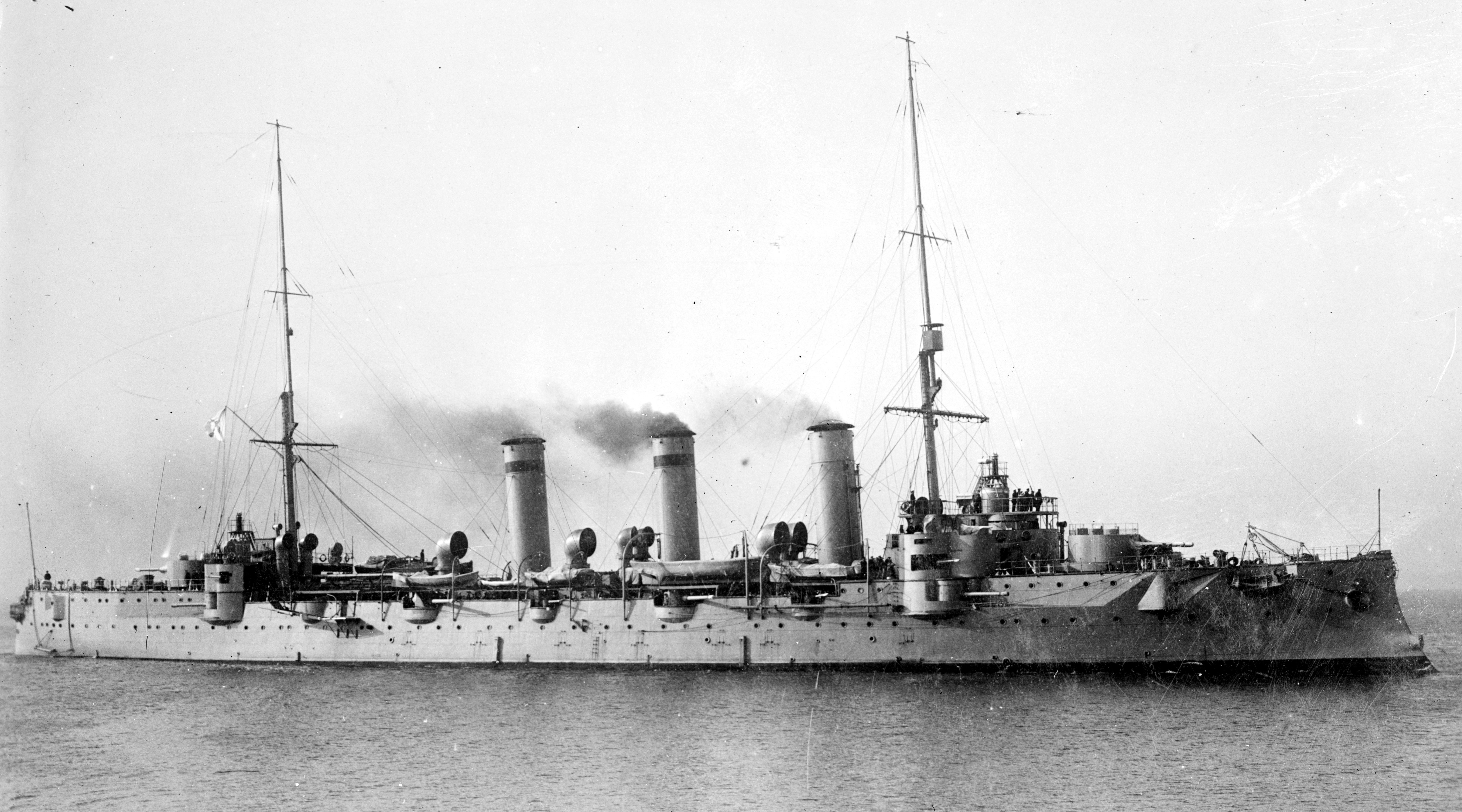

Much against the wishes of the Admiralty, the Royal Navy was thrown into this maelstrom. Only small ships were deployed, not the big and expensive battle wagons; light cruisers, destroyers, minesweepers, submarines, motor launches, eventually even an aircraft carrier, they were tasked with containing the Red Baltic Fleet battleships and cruisers based at Kronstadt, near St Petersburg.

The navy had been given this difficult task because neither Britain or France wished to commit troops to a new conflict; indeed, governments might have fallen if they had tried. It was a cheaper and lower political risk decision to use ships, a plan supported to the hilt only by Secretary of War Winston Churchill. Prime Minister Lloyd George was less than lukewarm, as were the rest of the British cabinet. However, through the navy, Britain could provide sea-based artillery support, prevent a breakout or raids by the Bolshevik fleet and supply arms and ammunition to the armies of the Baltic States.

After something of a false start in December 1918, in which a light cruiser was lost and another damaged, in 1919, Rear Admiral Sir Walter Cowan was placed in charge of this difficult mission. In one way he was the right man for the job, for he was aggressive by temperament and always looking for a fight to get into. On the other hand, he drove his men hard and without thought for their wellbeing. This would eventually have consequences.

The Communist army and navy, headed by Leon Trotsky, were unleashed by Lenin who declared ‘the Baltic must become a Soviet sea’. And so, from December 1918 and for the next thirteen months the Royal Navy was in action against Soviet ships and ground forces, inspired by Trotsky who ordered that they should be ‘destroyed at any cost’. Sea battles raged between the Red Navy and the RN with losses on both sides.

Eventually, in two daring actions, Cowan was able to neutralise the Bolshevik fleet; a tiny coastal motor boat commanded by Lieutenant Augustus Agar sank the cruiser Oleg, and then a squadron of similar vessels accounted for two Soviet battleships and a depot ship. Three Victoria Crosses were awarded for the bravery shown in these attacks.

Royal Navy ships were also involved in providing a constant artillery barrage in support of the forces of the Baltic States, protecting their flanks and helping drive back their enemies. Aircraft from an early form of aircraft carrier, the converted Hawkins-class cruiser, HMS Vindictive, also played a role in one of the first combined arms ship-carrier-air raids ever. As one Latvian observer recorded, ‘the Allied fleet rendered irreplaceable help to the fighters for freedom’. The navy even rescued British spies from the Russian mainland.

And the navy had also to face down local German commanders, gone ‘rogue’ and actively conniving in the overthrow of the legitimate local governments.

With the RN’s gunnery support, the armies of Estonia and Latvia were gradually successful in beating back their multiple foes. But it was a close-run thing. Only the intervention of the Royal Navy’s fire power saved Reval (now Tallinn) and the massive 15-inch guns of the monitor Erebus and her consorts drove the Russo-German invaders out of Riga when it seemed certain to fall into their hands.

There was a price to pay for these achievements; 128 British servicemen were killed in the campaign and sixty seriously wounded. Over the period of the naval effort, 238 British vessels were deployed to the Baltic and a staging base set up in Copenhagen, Denmark; nineteen vessels were lost and sixty-one damaged.

There was a cost in morale as well. The sailors and many officers did not understand why they were fighting there. They were not volunteers, and most British sailors simply wanted to go home to the UK. Politicians cavilled about the navy’s orders and role, and decisions and recognition were not always forthcoming. The living conditions for the navy were poor and the food was terrible. And the tasking was relentless and perceived as uncaring. Mutiny broke out on several vessels, including Admiral Cowan’s flagship, and sailors preparing to sail to the Baltic from Scotland deserted.

In February 1920 the combatants signed a treaty ending hostilities and an uneasy peace prevailed until 1940, when a greedy Russia snapped up the Baltics with German connivance. A war-weary Royal Navy had held the ring, fighting against Russian and German opponents alike. It had helped the Baltic States gain their freedom from Bolshevik terror and German revanche, if only for twenty years. And it is NATO, including the Royal Navy, which guarantees that freedom still.

Steve R Dunn

ENDS

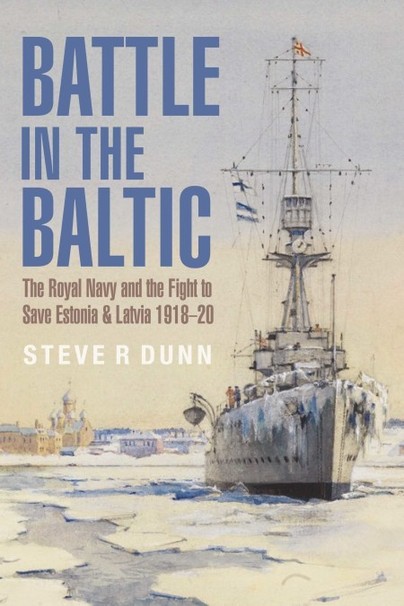

Bio: Steve R Dunn is a naval historian and author of eight books on the Royal Navy in World War One, with two more commissioned for 2021 and 2022. His latest book, Battle in the Baltic (Seaforth Publishing, 2020) tells the story of the Royal Navy and the fight to save Estonia and Latvia during 1918-1920.

Order your copy here.