Did Tiberius really kill Germanicus?

Author guest post from Alessio Perry

Since antiquity it has been tradition to narrate that the emperor Tiberius (r. 14-37 AD), jealous of the success and popularity of his young nephew and adopted son, Germanicus, had him killed in a conspiracy deign of one of Agatha Christie’s novels. By carefully re-examining the historical record and combining it with some archaeological evidence, however, another story begins to emerge.

The tradition

Germanicus was the eldest son of Tiberius’s younger brother, Drusus Maior (so called to distinguish him from Tiberius’s own son, Drusus Minor), a valiant and beloved general during the early reign of Augustus (r. 27 BCE-14 CE). In 4 CE, when Augustus formally adopted Tiberius as his heir, he also had Tiberius adopt Germanicus, since the young boy shared his own blood (as it happened, Germanicus was the grandson, via his mother, of Augustus’s only sister, Octavia). When Augustus passed away ten years later, Tiberius became the new princeps (i.e., “first among equals”, as the emperor was formally known at the time), and Germanicus took his place as heir presumptive. So, what are the reasons which allegedly led Tiberius to dispose of his adopted son and heir?

Problems arose straight away. In the fall of 14 CE legions stationed in Pannonia (modern-day Hungary) and along the Rhine river rebelled to the new emperor, asking for benefits promised to them by the late Augustus. The soldiers on the Rhine, however, also asked Germanicus – at the time in nearby Gaul – to rise in arms against his uncle-father and to become the new emperor (Cassius Dio, Roman History, 57, 5; Suetonius, Life of Tiberius, 25; Tacitus, Annals, 1, 31). This Germanicus did not do, repeatedly refusing the soldiers, at times at risk of his and his family’s indemnity. Once the rebellion was quelled, Germanicus decided to raid the territory beyond the Rhine, home to many hostile Germanic tribes; in so doing, he hoped to satiate the need of expiation felt by the soldiers. The raid proved a success, and one of the legionary eagles lost by Publius Quintilius Varus during the crashing defeat at Teutoburg in 9 CE was even recovered. The following year, 15 CE, during another campaign, Germanicus’s legions reached the forest of Teutoburg itself; the erection of a monument to the fallen soldiers and the recovery of another of the lost legionary eagles increased the young general’s popularity even more (Cassius Dio, Roman History, 57, 18; Tacitus, Annals, 60-61). But it was Germanicus’s victory in 16 CE over Teutoburg’s mastermind, Arminius, which crowned his military achievements.

At this point, the sources tell us that Tiberius decided to call back Germanicus, thus preventing him from expanding Rome’s dominion (and increasing his own glory with it). All sources state that the emperor needed his son in the eastern provinces of the empire, where fresh troubles had arisen; however, they also declare that the real motive behind the emperor’s decision was fear and jealousy for his nephew’s achievements and popularity, which now obscured his own and those of his biological son Drusus. Moreover, Germanicus’s jolly and agreeable personality contrasted with the emperor’s introvert character, thus alienating Tiberius from popular favour even further.

In the east, Tiberius made sure that Germanicus was monitored by his newly appointed governor of Syria, Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso, a conservative and intransigent senator. This created a lot of resentment between Piso and the young man, interspersed with a few diplomatic ‘accidents’ (Tacitus, Annals, 55-57). Then, according to the sources, it was Germanicus’s triumphant entry into Egypt which proved to be the definitive breakdown in relationships between the emperor and himself. This was apparently due to the fact that Germanicus had entered Alexandria, Egypt’s capital, without asking prior approval from his uncle (Suetonius, Life of Tiberius, 52; Tacitus, Annals, II, 59; a disposition of the emperor Augustus prevented any senator from entering Egypt without his – and successive emperors’ – consent). When Germanicus suddenly died in 19 CE, it was easy to believe that something was amiss. In his dying words, the young man pointed the finger to Piso as the architect of his death. Eyes immediately turned to the governor; and since it had been Tiberius who had sent the old senator to Syria in the first place, this constituted the unassailable proof which confirmed the emperor’s complicity and culpability in the murder of his nephew (Suetonius, Life of Tiberius, 52). Additionally, the fact then that neither the emperor nor his mother participated to Germanicus’s funeral in Rome – and also prevented Germanicus’s own mother, Antonia, to attend – was taken as concrete proof of their sneaky actions (Tacitus, Annals, III, 3).

Reading through the lines

Such is the tradition inherited from our classical authors. However, by reading carefully through the lines, some things do not add up, and some archaeological evidence can also come to our aid to clarify the issue further.

Let’s begin with Germanicus’s time in Germany, during the legionary revolt of 14 CE. Tiberius was said to be fearful for his own position, threatened by Germanicus’s popularity among the soldiers and by what he could have done with their support, if he wanted. He could have done it, but he didn’t. Germanicus remained loyal to his uncle throughout the revolt, to the point of once threatening to kill himself had the soldiers not let him go (Tacitus, Annals, I, 35). Such an episode makes us also question the love which the soldiers are said to have had for their general – and many others similar to this one dot Tacitus’s account of the events throughout. Moreover, Tiberius had bestowed upon Germanicus the imperium proconsulare, which allowed him to administer freely the lands assigned to his jurisdiction and to control the military forces stationed there. No emperor would have given such a power to someone else, even to his own relative, if he had not been worthy of his trust.

Next, Tiberius is accused of having recalled Germanicus from beyond the Rhine because of sheer jealousy for his victory over Arminius (the need for him to go East tends to be sidelined). It is usually forgotten that Tiberius, himself a valiant and successful general, had served on the German frontier for a long period, the last time between 10 and 12/13 CE, just before Augustus’s death. He had thus been able to get to know the enemy well and to understand what strategy could work best against them. The German forests were an inhospitable land, very difficult to control, and all the Roman efforts in managing the area beyond the Rhine were nullified by Varus’s defeat in 9 CE. Tiberius allowed Germanicus to claim revenge over such a disaster, and the battle of Idistavisus can be said to have regained the legions’ lost honour. Meanwhile, however, fresh troubles in the East had broken out, and the emperor recalled Germanicus reckoning him to be the most suitable candidate (by rank and experience) to deal with the situation. In Germany, diplomacy replaced overt warfare; and what proves Tiberius’s longsightedness in his settlement of the area is the fact that the Rhine frontier remained undisturbed well into the III century CE, bar brief interruptions.

Before Germanicus’s departure for the eastern provinces in 17 CE, Tiberius conferred on him the imperium maius, which gave him absolute authority (second only to the emperor’s) over all the provinces “divided by the sea” (Tacitus, Annals, II, 43). Was Egypt part of these provinces, though? Some elements point out that Germanicus may have thought so: in the Papyrus Oxyrhyncus XXV 2435, which reports a speech Germanicus pronounced in front of the inhabitants of Alexandria, the young general calls himself “an envoy of Tiberius”. Moreover, we must not forget the main reason for which Germanicus had gone to Egypt in the first place: to “look after the province” because of an ongoing famine, in words of Tacitus (Annals, II, 59-60; also Suetonius, Life of Tiberius, 52). Perhaps Germanicus, as son of the princeps and holder of imperium, believed he did not need a formal authorization from his stepfather to enter Egypt; or perhaps, because of the rapid spread of famine in the province, he thought best to act quickly so that the regular shipment of grain to Rome may not be affected. There is, however, an interesting detail: Tiberius is said to complain about Germanicus’s entry into Alexandria, but he never seems to refer to Egypt itself. What could have he possibly feared from this city? In the same papyrus mentioned above, Germanicus refuses the divine tributes that the inhabitants of the city had offered him; he replies that, if any offering had to be given at all, it should be directed to the emperor and his (Tiberius’s) mother, Augustus’s widow. A strange thing to say, if the general was planning any revolt against his uncle! Furthermore, if Germanicus had really entered the country “illegally”, such insubordination would have surely provoked Tiberius’s harsh reaction, which no source would have failed to pick up; instead, Tiberius is reported to have just complained that he had not been consulted about the visit beforehand (Suetonius, Life of Tiberius, 52). Interestingly, Robin Seager (1972, 104) noticed that the sources do not even mention any opposition from the governor of Egypt; this detail increases the probability that everything took place within the boundaries of legality.

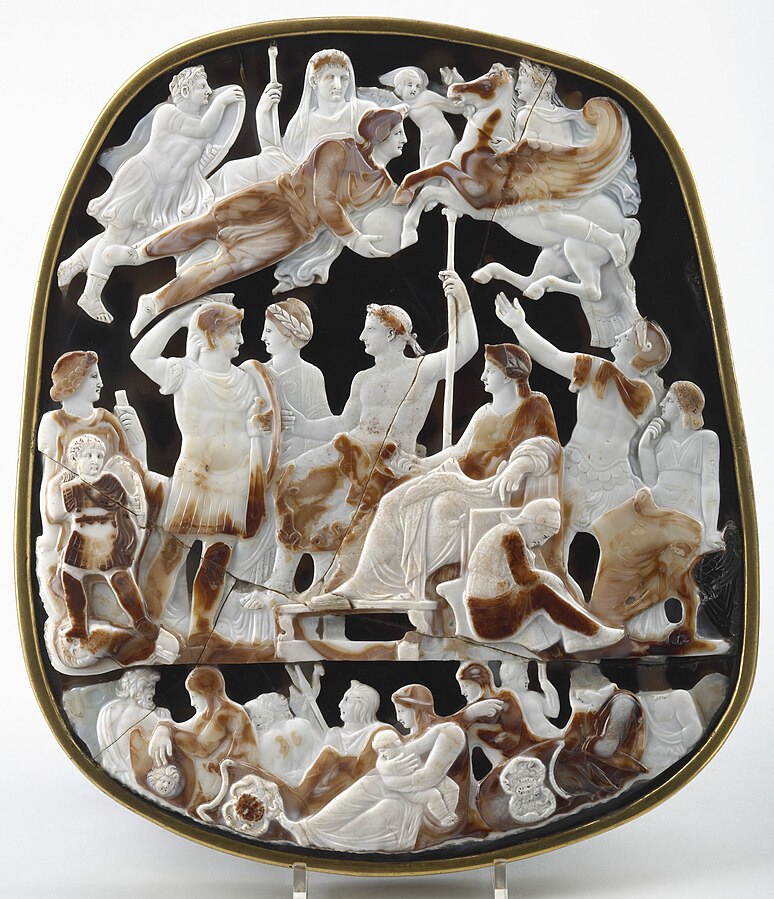

Another element testifying to the good relations between Germanicus and Tiberius comes from the archaeological record. We know from excavations that, in 19 CE, Tiberius had erected in the Forum of Augustus in Rome two identical monumental arches: one to honour his son Drusus for his military achievements on the Danube, the other glorifying Germanicus’s deeds beyond the Rhine and in the East. The late emperor Augustus had done something similar for his grandsons and heirs Gaius and Lucius, before their premature death. Also, from the caravan city of Palmyra, in modern-day Syria, comes an inscription once part of a group of statues celebrating Germanicus’s extension of Roman influence to this area for the first time. From the inscription we know that the sculptures represented Tiberius, Germanicus and his stepbrother Drusus. Such examples illustrate that the commissioners of these works – Tiberius in the case of the former, Germanicus for the latter – wanted to show cohesiveness and harmony in front of their subjects, and that no formal distinction was ever made by the emperor between his own biological son and his adoptive heir.

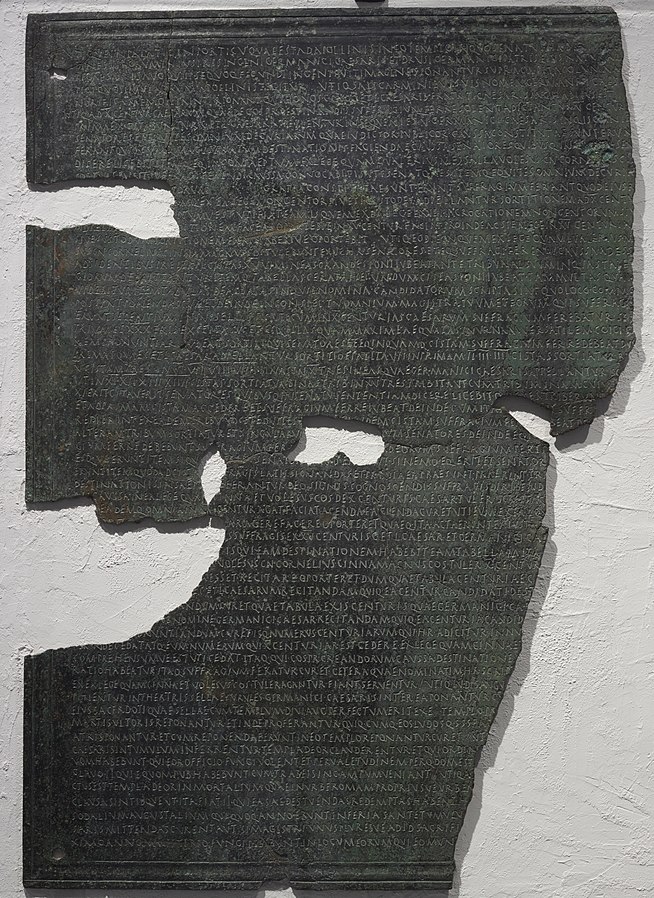

Now let’s turn to the enigmatic Piso. Tacitus (Annals, II, 43) states that this man was so arrogant that “he barely gave way to Tiberius himself and, as for Tiberius’s children, he looked down on them as far beneath him”. Even Suetonius (Life of Caligula, 2) reports that Piso, when governor of Syria, “could not hide his displeasure to either father or son” (Tiberius and Germanicus respectively). So, why would Tiberius choose someone like this to administer one of the wealthiest provinces of the empire? Tiberius had apparently assigned Piso to Germanicus as collaborator after a Senate’s proposal (Tacitus, Annals, III, 12); this should be evidence enough to discharge him from any later accuse of premeditate murder. However, we also possess an extraordinary document which can corroborate the emperor’s innocence even further. This is the original text, preserved on a bronze slab, of the senatus consultum (i.e., Senate’s disposition) regarding the trial of Piso over Germanicus’s death in 20 CE. Among all the accusations to Piso’s conduct, the one of poisoning the young prince was the only one to be debunked. According to the eldermen, Germanicus’s usual moderation and tolerance had been overcome by Piso’s “fierce” character and this had led him to believe that it had been the same Piso who had him poisoned (Eck et al. 1996, 26-28). Thus, even in his alleged dying words, the young man made no mention of his uncle. Piso ended up being charged of mismanagement and corruption during his time in Syria, something that even Tiberius was irate about; but not of murder.

It remains to be seen why Tiberius decided not to attend Germanicus’s funeral and, in so doing, also allegedly prevented his nephew’s mother, Antonia, to participate. We know that the emperor always had cordial relations with his sister-in-law; it was also Antonia who convinced him, later on in the reign, of what danger to his position his praetorian prefect, Sejanus, represented – something she would not have done, had she resented him (Tacitus, Annals, III, 2). Tiberius’s quick reaction in disposing of his omnipresent adviser shows the trust he put in the advice and opinion of his sister-in-law. If there was still trust in 31 CE, the year of Sejanus’s fall, it is improbable to believe that trust was not present at the time of Germanicus’s death. It is thus more probable that Antonia herself decided not to attend his son’s funeral, wishing to present a cohesive front with Tiberius and his mother Livia. Moreover, the “coldness” which the sources attributed to Tiberius was a trait of his own vision of the state. According to this, private matters must not in any way interfere with the ordinary, daily running of government. No exceptions could be made; the state could not wait. And it was not only for Germanicus that Tiberius kept away: he kept attending Senate sessions throughout the terminal illness of his biological son Drusus (Tacitus, Annals, IV, 8); when his mother died, he did not attend her funeral either (Tacitus, Annals, V, 2); and he did not even participate to the wedding of two of Germanicus’s daughters (Cassius Dio, Roman History, 58, 21). It was all part of a sense of decorum inherent in Tiberius’s conservative character. He was very conscious of his aristocratic and republican heritage (his family, the gens Claudia, was one of the oldest and most illustrious of the old republic) and, thus, he could not be seen to put private ordeals before matters of state. Duty first.

Who really killed Germanicus?

If Tiberius was not the culprit, as I hope to have demonstrated, then, who killed the hope of Rome? We can’t really be sure. We saw that Piso was discharged from having murdered Germanicus. It might have been Piso’s wife, Plancina, who used the poison, just to spite Germanicus’s wife Agrippina, with whom she was often at loggerheads. But it’s more probable that Germanicus was simply taken away by a sudden illness – something too common until the appearance, only recently, of better medical care and hygiene.

To know more:

Cassius Dio, Roman History

Suetonius, Life of Tiberius; Life of Caligula

Tacitus, Annals

Eck, Werner, Caballos, Antonio, Fernandez, Fernando, 1996. Das Senatus consultum de Cn. Pisone padre. Muchen: Verlag C.H. Beck.

Gallotta, Bruno, 1987. Germanico. Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

Levick, Barbara, 1976. Tiberius The Politician. London: Routledge.

Seager, Robin, 1972. Tiberius. London: Eyre Meuten.

Order your copy here.