Women’s History Month – Sarah J Hodder

The Grey lady…

I first came across Elizabeth Grey whilst researching my book on Cecily Bonville-Grey, Marchioness of Dorset – Elizabeth’s mother. Elizabeth is one of the three protagonists in ‘The Woodville Women’ alongside Elizabeth Woodville (queen consort to Edward IV) and her daughter, Elizabeth of York, who became the first Tudor queen consort as the wife of Henry VII. Elizabeth Grey was the granddaughter of Elizabeth Woodville and niece of Elizabeth of York.

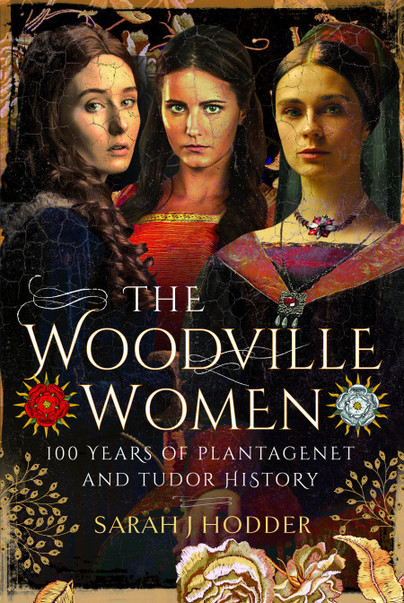

With no contemporary image of her available to us (or at least none I have been able to find), I often look at the beautiful cover of The Woodville Women (thank you Pen and Sword!) and wonder which one best represents her. Mostly I conclude it’s the one in the middle; the one in the background with the look of steely determination in her eyes. That’s how I have come to view Elizabeth Grey, as a woman with tenacity and staying power.

When I looked up the term ‘the grey lady’ for this blog piece, the term is often used to describe someone who is neutral and dull. ‘Vanilla’ is another word. Elizabeth Grey was perhaps the very definition of the grey lady, not just by name, but it is a compliment. It was undoubtedly her neutrality that made her one of life’s survivors. Her ability to not offend, to empathise, to be kind and to be liked and respected by all helped her navigate the politics and intrigues of the world she lived in. She may have been ‘grey’ but she was certainly not dull!

The daughter of Cecily Bonville-Grey and Thomas Grey, 1st Marquis of Dorset, Elizabeth Grey was likely named after her grandmother, although it is possible they never met. Queen Elizabeth Woodville took her last breaths on Friday 8 June 1492 at fifty-three years old. Elizabeth Grey’s birthdate, like her numerous brothers and sisters, went unrecorded, but evidence points to the fact that she was born sometime in 1492; mostly likely named after her grandmother whose death the family were mourning.

Elizabeth was born seven years into the reign of Henry VII. Little is known of her early years but it is highly likely that she knew and spent time with her cousins, Prince Arthur and Henry Tudor and the princesses Margaret and Mary. In 1514, when Elizabeth was twenty-two years old, and five years after her cousin had ascended the throne as Henry VIII, Elizabeth was selected to accompany her cousin Mary to France, as one of the ladies who would serve her during her marriage to the ageing King Louis of France. These were honoured positions and one of the criteria for Mary’s companions was that they must be competent in French. It was reported by the Venetian ambassador, Pasqualigo, writing home on 23 September 1514, that in the hope of securing a place in her entourage, the whole court now speaks French and English. That Elizabeth, and her sister Anne Grey were selected, indicates that they must have been fairly well educated and had some mastery over the French language. The ladies who accompanied the princess Mary to her new life were named in the official records as Lady Guildford, Elizabeth Ferrers, Ann Devereux, M. Wotton, Alice Denys, Anne Jerningham and an M. Boleyne, who is believed to have been Mary Boleyn. These women were Elizabeth’s contemporaries.

After the marriage, for reasons unknown, King Louis dismissed many of Mary’s English ladies but Elizabeth was permitted to stay alongside her sister Anne. The other ladies Mary was allowed to retain were Anne Jernyngham, Mary Fiennes, Mary Boleyn and Elizabeth Ferrers. Anne Boleyn would also shortly join this group, fresh from the court of Margaret of Austria.

When King Louis died just a few months into the marriage, Princess Mary took her brother at his word (that she would be free to choose her second husband) and married the man she really loved, her brother’s good friend, Charles Brandon. When Mary and Charles returned to England to face Henry’s wrath, Elizabeth said goodbye to her sister, Anne, and chose to remain in France. She transferred into the service of Queen Claude, alongside Mary Fiennes and Anne Boleyn.

Elizabeth served the French queen for around two years. A devout woman with a strict moral code, Claude was thought to be a good mistress. With a household based mainly at Blois, Elizabeth would also have spent time at the court of the flamboyant French king, Francis, at Amboise. Here, Elizabeth would have experienced a much more lively and raucous court. Francis was almost the complete opposite of his wife – tall and athletic and a notorious womaniser, with several mistresses. During her time in France, Elizabeth may also have come into contact with the formidable Louise of Savoy, the mother of King Francis, and very possibly the Italian artist, Leonardo da Vinci, who was housed and employed by the king.

By May 1517 Elizabeth had ended her time in Claude’s service and had returned to England, perhaps to the household of her cousin, the Princess Mary, or perhaps into the household of Henry’s queen, Katherine of Aragon. Once again in 1520 she returned to France, this time as part of the lavish festivities which we know as the Field of The Cloth of Gold, travelling as part of Queen Katherine’s retinue. Their destination for this once in a lifetime event was a picturesque French valley between Guisnes and Ardres. Aged twenty-eight at this point, she likely spent two glorious weeks in the countryside of rural France, housed in one of the many tents constructed on the site of varying sizes and colours, some plain white, others in the Tudor colours of green and white and some of the bigger tents decorated with gold and divided into several rooms within. It may have been during this trip that she first met the man she would marry; Gerald Fitzgerald, the 9th Earl of Kildare.

The Earls of Kildare had been both allies and troublesome thorns in the side of the English kings for many years. Gerald’s father, the 8th Earl, had been held prisoner by Henry VII in the mid-1490s for nearly two years. A hugely powerful and charismatic figure, when charged with sacrilegiously burning down the church of Cashel he allegedly confessed the fact that he had indeed burned it down, pleading as his defence that ‘he thought the archbishop was in it’.

His son, Gerald Fitzgerald, who had become the 9th Earl upon his father’s death in 1513, was built from the same mould. Like her cousin Mary had done before her, Elizabeth fell in love and married without her family’s permission, probably earning their wrath, although eventually causing her mother to write that she had now paid all her daughter’s dowries, including to her daughter, Elizabeth, Countess of Kildare, even though she married ‘without the assent of her friends, contrary to the will of the lord marquess her father….. forasmuch as the said marriage is honourable, and I and all her friends have cause to be content with the same’.

When Elizabeth met the Earl, he too was being detained at the English court, and like his father he too had a likeability that charmed king Henry VIII as much as it worried him. Elizabeth’s father, the Marquis of Dorset, had died many years before but had obviously left strict instructions for the marriages of his daughters. But it seems the charismatic earl, famed for his handsome good looks and affable character, was able to win around his new family as Elizabeth’s mother and four brothers all put up bonds for Kildare’s appearance before the king in 1521.

By 1523, Kildare was ‘released’ by King Henry and given permission to return back home. As the Countess of Kildare, in January 1523, Elizabeth once again boarded a ship, but this time she was not sailing south, but west across the Irish Sea to the beautiful, wild country that would become her home. Her destination in Ireland was the Fitzgerald stronghold of Maynooth Castle within the English Pale, where she would spend much of the next eleven years. But it would not be a peaceful life; trouble followed the Earl around, and much of their life was spent in arguments and disputes with other noble families, headed up by men like the Earls of Desmond and Ormond. The Earl of Kildare, clearly no saint, had the almost impossible challenge of representing a faceless English king to the people in Ireland and when he wasn’t embroiled in feuds with the Irish Earls, he was getting into trouble with the English Crown itself. The Earl of Kildare would be hauled back to England more than once to answer to his king and by 1534, he found himself once more imprisoned in the Tower, ill and dying. By then seen as an enemy of England, Henry VIII’s respect for his cousin is perhaps most illustrated here as he allowed her to nurse her dying husband in the Tower. Elizabeth remained with the man she loved until his death on 12 December 1534.

After his death, Elizabeth was effectively forbidden from returning to Ireland. Whilst she took refuge at her brother’s house in Leicestershire, her stepson, Silken Thomas, the Earl’s son from his first marriage rampaged through the English Pale, angry at the treatment of his father. Eventually captured along with his Kildare uncles, Elizabeth may have received the news of the capture and eventual execution of her stepson and brothers-in-law with some sadness. In the meantime, her eldest son with Kildare, also named Gerald and only nine years old at the time of his father’s death, was being smuggled between families in Ireland, loyal to the Kildares, who kept him safe from the king’s men who were anxious to get him into their charge. Eventually young Gerald was dispatched safely overseas; Elizabeth would not see her son again until just before her own death.

Now a widow, aged forty-two years old and back home in the country of her birth, she lived the rest of her years in Leicestershire. She would outlive her cousin, King Henry VIII, and remained on good terms with him. During her later years she dined with Eustace Chapuys, mourned the deaths of Katherine of Aragon and her cousin, Mary Tudor, and may have served as one of Katherine Parr’s ladies. Two of her other children, who had accompanied her to England, would become playmates to Henry’s children, Prince Edward and the Princesses Mary and Elizabeth. Elizabeth Grey maintained good relationships with them all. In later years, she and her daughter kept up correspondence with the king’s daughter, Princess Mary, and often sent her gifts. Elizabeth’s daughter, also named Elizabeth, would serve in Princess Mary’s household as an young woman and the households of Henry’s fifth and sixth queens, Katherine Howard and Katherine Parr. Later in life, Elizabeth’s daughter would become Lady Elizabeth Clinton, becoming one of Elizabeth I’s closest friends and an important part of her inner circle.

Elizabeth Kildare (nee Grey) died sometime around 1550/1551, during the reign of Edward VI and just two years before her great great niece, Lady Jane Grey, became England’s nine-day queen.

Because of her quiet resolve, Elizabeth has perhaps faded into the background more than her contemporaries. But her chameleon-like ability to be liked by all, to keep her cousin the king on side even whilst her husband is branded a traitor, to be friends with Katherine of Aragon and Mary Tudor as well as mixing with families like the Boleyns, is what made her a survivor. We can never determine a person’s character from such a distance of time but looking at her actions, it seems Elizabeth may have chosen to empathise with others, to not outrightly offend. But alongside that, Elizabeth Grey was no doormat; she was not afraid to marry the man she loved without her family’s permission, nor was she afraid to plead with the king for the lives of her family, an act that could have thrown her into danger herself. She sided with Katherine of Aragon and her daughter, Princess Mary, but seemingly without making enemies elsewhere. And she seems to have maintained this quiet tenacity and strength of determination throughout her life. Because she was so uncontroversial, her story has faded into history. Undeservedly so.

You can read more about Elizabeth Grey alongside her grandmother, Elizabeth Woodville, and her aunt, Elizabeth of York in The Woodville Women: 100 Years of Plantagenet and Tudor History.

Order your copy here.