Author Guest Post: Anthony Burton

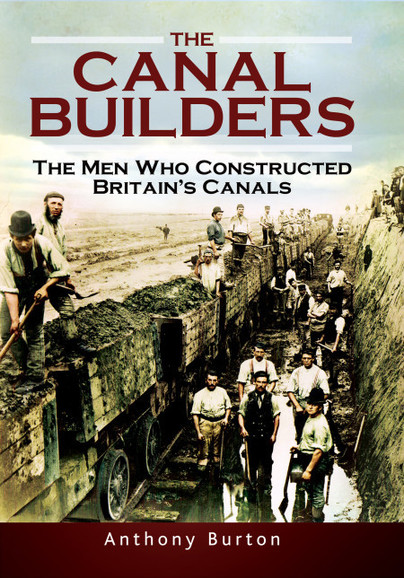

THE CANAL BUILDERS

This book might never have happened at all, if my writing careers had gone the way I first intended. I left a career in publishing in order to write full time in 1979 and I started out as a humourist. My first book, A Programmed Guide to Office Warfare, was a success – hard back and paper back in Britain and America and translated into other languages – I have an incomprehensible to me copy of the Japanese book. But my next effort, The Jones Report, sank without causing a ripple on the surface of the literary world. My agent Murray Pollinger then asked a very pertinent question: “What is the book you have read in the past year that you wished you had written yourself?” My answer was The Railway Navvies by Terry Coleman. The next question was obvious: was there a similar subject that interested me? My wife and I had already taken to enjoying canal holidays and I had become increasingly interested in their history. One element that seemed to be lacking was any information about the people who had constructed them. There were biographies of the main engineers, but very little about anyone else – their hard-working assistants, the administrators, the contractors and, of course, the navvies. I wrote an outline and Murray got me a very good contract, for what was to become The Canal Builders.

The main sources of information that I used were the official documents of the different canal companies held in what was then the British Transport Archive housed in a building near Paddington station. I made a list of the British canals, with the dates of the Acts authorising the construction and the date of opening. I then began the task of searching the catalogue to find which company records survived that covered those periods. One of the most productive sets were those of the Lancaster Canal. The Company Secretary, Samuel Gregson, was a harassed man – summed up in a letter he wrote to the chief engineer. “This has been a day of complaints and I am heartily tired of them.” His letters record endless arguments with the contractors. The company wanted everything done thoroughly: the contractors wanted everything completed as quickly as possible. It was the secretary who had, for example, to try and pacify angry landowners, when the contractors moved in before the land sale had been completed. The same company records gave a picture of the life of the assistant engineers, the men who, unlike the chief engineer, were on site all the time. The greatest work was the construction of the Lune aqueduct, where the engineer in charge lived in a wooden hut with the man responsible for the steam engine installed at the workings – who, unfortunately, was often very drunk. Gradually I was building up a picture of the working life of the canal builders.

There were also folders of documents, simply referred to in the catalogue as “miscellaneous”. One of these folders was dated to the 1790s, the busiest period of canal construction. I filled out an order slip and waited for the documents to arrive. Most of the staff were helpful, but there was one dour individual who seemed to begrudge passing anything on to researchers who were not academics. On this occasion, he asked me which particular documents in that file I wanted. I explained that as they weren’t listed. I couldn’t be specific. At this point, things took a turn for the worse. His argument was that as they weren’t catalogued, there might be valuable documents that I could slice out with a razor and sell. I was, and am, bearded, so I tried to lighten the mood: “As you can see, I don’t use a razor”. To which he replied: “Not for shaving perhaps”. It was only when I threatened to put my case to his superiors that I got the documents. It would be good to end this story by reporting they were invaluable: in fact, they had nothing of interest. But in a bundle that came up later, I did find an uncatalogued letter from Thomas Telford. I did not bring in a razor the next day.

One area where information was scant was the one in which I had first become interested: the Navvies. They were an almost anonymous army of men. A typical entry referred to the death on the Leeds and Liverpool Canal of a navvy, who was simply described as “a stranger called Thomas Jones supposed from Shropshire.” As well as canal records, I also spent time looking through the newspapers of the time and they did mention these men, but not to describe their lives and what they did. They came to the public’s attention when they were involved in riots. One of the worst occurred at Sampford Peverell on the Grand Western Canal. Many contractors, as here, paid the men in tokens, which in theory they could use as coins of the realm. When they found that shopkeepers and publicans wouldn’t accept them, there was a riot in which one navvy was shot dead. The reputation for rioting was so strong, that at an election, the men were lured away from the Lancaster Canal by one of the candidates, which the official records noted “can be for no other purpose than to riot and do mischief”. It was possible to build up a picture of what these men did, how they worked and lived, but with none of the detail that Terry Coleman found for the railway navvies. But I felt that from the wealth of material I had obtained, I had a pretty full picture of all the different men from many different backgrounds who had built up a network of canals that covered the whole country.

The book first appeared in 1972 and I have always been on the lookout for other snippets of information to help build up an even fuller picture. There are , for example, several broadsheet ballads about the railway navvies, and I have always been looking for something similar for the canals, and one folk singer told me he knew an authentic 18th century song. When I told him it was not genuine, he was quite offended, but I had the clinching argument: I wrote it. I did, however, collect more information on different aspects of the subject as I continued to research and write canal history. The result is that now there is a paperback edition of the fifth edition. And it all began with a pertinent question in a London office fifty years ago.

You can preorder a copy here.