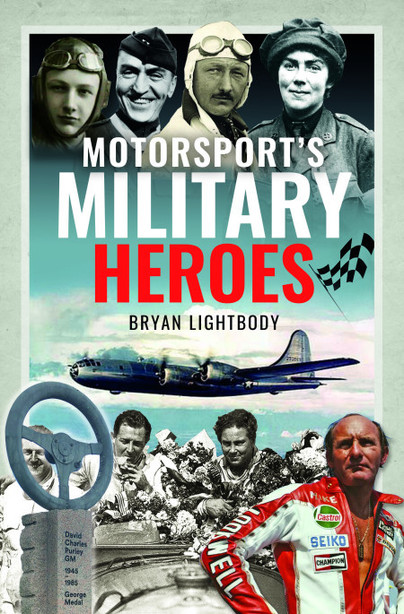

Author Guest Post: Bryan Lightbody

As previously highlighted, my enthusiasm for historic motorsport coupled with writing and battlefield guiding lead me to produce (what I hope will be) Volume one of ‘Motorsport’s Military Heroes’. It showcases some extraordinary individuals who braved all in war and on the racetrack. Male and female competitors, it profiles individuals who raced from the 1920s up to the 1970s.

Moving on, starting to examine the subjects on an abridged basis to give a flavor of the book, we’ll start with two of the Bentley Boys, Great War veterans who continued to risk all on the track after the war.

Captain Woolf Barnato, Royal Field Artillery WW1, later Wing Commander RAF in WW2, three time Le Mans winner & Bentley Boy.

Joel Woolf Barnato born 27th September 1895, was a British financier and racing driver, becoming one of the famous ‘Bentley Boys’ of the 1920s. He ultimately achieved three consecutive wins out of three entries in the 24 Hours of Le Mans race. He was also a veteran of both World War One and Two. Woolf Barnato was powerfully built and given the sobriquet ‘Babe’ that was either a reference to his position as the third and last of the family children, or an ironic nod to his stocky six-foot frame. Barnato was educated at Charterhouse School and then at Trinity College, Cambridge where he made a name for himself as a boxer, and also where he was renowned for flooring the heaviest of boxing ‘blues’. Along with his brother he joined the Officer Training Corps at university, a move that would stand him in good stead.

When The Great War broke out in 1914 he enlisted as a second lieutenant and eventually became a captain, serving in France, Egypt and Palestine in the Royal Field Artillery in the British Army. His older brother Jack was a pilot during the war involved in the bombing of Constantinople and was mentioned in dispatches before his death from pneumonia in 1918. His military career is detailed further in my book.

Barnato began motor racing in 1921, when after importing an eight-litre Locomobile from the United States, he signed-up to race at the Brooklands Easter meeting. In late 1924 Barnato obtained a prototype Bentley 3.0 litre chassis, which was subsequently fitted with a boat-tail body by the Jarvis company at a cost of £400. Barnato used the car to win several major Brooklands races, and then partnered by fellow ‘Bentley Boy’ John Duff set a new 3.0 litre 24-hour record averaging 95.03 miles per hour at the Autodrome de Montlhéry. Barnato officially purchased his first 3.0 litre Bentley in 1925 from the company.

The 1928 season saw the official Bentley team include the Grosvenor Square ‘Bentley Corner’ residents; Tim Birkin, Glen Kidston, Bernard Rubin and of course Woolf Barnato. 50 Grosvenor Square had been christened ‘Bentley Corner’ by cab drivers because of these four drivers all living there. Bentley won with Barnato and Kidston in a 4½ litre model.

The 1929 Le Mans race saw Bentley take the first four places, Barnato taking the victory although this time with co-driver and fellow wealthy socialite Sir Tim Birkin, with Kidston taking the second place.

In 1930 Barnato with Glen Kidston won again in a Bentley Speed Six. These were the only years in which he entered the race, leaving Barnato as the only Le Mans driver with a perfect wins-to-starts ratio. After track racing, for Barnato came racing against trains from the south to the north of France, quite a feat.

From 1940 to 1945, Barnato was a wing commander with the Royal Air Force, responsible for the protection of aircraft resources against Nazi Luftwaffe bombing raids. The role he undertook was to coordinate the protection of the twenty-five airfields of 11 Group in the south of England, as they were vulnerable to either attack to destroy aircraft or use for landing by an invading force. He was given the rank of wing commander for this appointment, equivalent to his former army rank of captain.

Barnato died at the London Clinic, Devonshire Place, on 27th July 1948 as a result of a thrombosis brought on after an operation for cancer. He was just short of his fifty-third birthday. His funeral cortege was led by his racing Bentley ‘Old Number One’, which was covered with flowers and wreaths. He is buried at St Jude’s Church in Englefield Green.

Barnato’s obituary in Motorsport Magazine in September 1948 was a fitting tribute.

Sir Henry Ralph Stanley ‘Tim’ Birkin was born 26th July 1896. He was a British Great War pilot and racing driver becoming another of the ‘Bentley Boys’ during the 1920s.

He joined the Royal Flying Corps during World War One, although his enlistment is with the 7th Battalion The Nottinghamshire & Derbyshire Regiment, the famous ‘Sherwood Foresters’. By the 16th January 1917 he was posted to 81 Squadron and is shown posted to Egypt. His records indicate repeated periods from August 1917 of being unfit for duty which was the consequence of him contracting malaria. He appears to be effectively not fit for air service between 1st August 1917 to 6th March 1918, even being hospitalised during February 1918.

Come July 1918 still posted to ‘The Middle East’, which is regarded as possibly Egypt which features for a single record entry, or Palestine as recorded by other research, he was an assistant flying instructor. He remained fit for service (FFS) into January 1919, when assuming a relapse in his health from the effects of malaria, he was signed off as ‘fit for ground service’ for three months. Then at the end of June he was invalided back to the UK. On the 29th July 1919 he resigned his commission. He was subsequently appointed full Lieutenant on a reserve commission on 16th April 1926 to the Norfolk and Suffolk Yeomanry, a territorial regiment and at the time he owned the Tacolneston Estate in Norfolk.

In 1921 he turned to motor racing, competing in a few races at Brooklands. He raced a French marque called DFP (Doriot, Flandrin & Parent). Business, marriage and family pressure then forced him to retire from the tracks until 1927 when he would return in a 3.0 litre Bentley for a six-hour race as one of the ‘Bentley Boys’.

Birkin personified, as did all the Bentley Boys, heroic insouciance and this was highlighted by how he recalled his determination to break the lap record at Brooklands. ‘I was in Le Touquet with Babe Barnato where he bet me at dinner in the casino that I would not break the lap record at Brooklands. I flew to Brooklands where there was a crowd and I took the car round once to warm it up. After that I tried to never lift my foot from the accelerator. Over the bumpy surface I was once in the air for forty feet with the car. I did two laps at 134.6mph and 135.3mph and so set up a new lap record. I flew back to Le Touquet in the evening and had dinner back with Babe’.

Birkin was known for his stylish appearance as much as he was for his flair for driving at speed. Young men of the day looking for the style trends observed that he was impeccably turned out in a checked tweed sports jacket and grey flannel trousers.

In 1928 he became a works Bentley driver, joining the ranks of the high-profile Bentley Boys that included Woolf ‘Babe’ Barnato, Glen Kidston and Bernard Rubin, all of whom were fellow Great War veterans. At Le Mans he drove a 4½ litre Bentley leading the first twenty laps until a jammed wheel forced him to drop back, finishing fifth by the end of the race. He had blown a tyre that eventually wrapped around the axle and brake drum buckling the wheel delaying him three hours.

The 1929 Le Mans saw Birkin back as winner, racing the ‘Speed Six’ as co-driver to Woolf Barnato. The race could be seen as a procession of Bentleys with the team taking first, second, third and fourth places. Clearly Birkin’s slightly rash ‘pressing on’ driving style was complimented by Barnato’s perhaps more measured approach to achieve victory.

In 1929 Birkin established his own motor works in Welwyn Garden City and he had moved out of the Norfolk estate as his means were running short following a divorce, his racing, living the high life and investing in car development. He was keen, with the complete disapproval of W.O, of boosting the performance of the 4 ½ litre Bentley by fitting a supercharger. W.O Bentley’s view was, ‘To supercharge a Bentley is to pervert its design and corrupt its performance.’ Birkin engaged with the company Amhurst Villiers and with Barnato the defacto owner of the marque, Birkin persuaded him to produce fifty ‘blowers’ to enable the Blower Bentley to enter Le Mans.

After the 1930 Le Mans, Birkin took second place at the French Grand Prix at Pau driving a stripped-down supercharged Bentley.

In 1933 he entered the Tripoli Grand Prix (having become Sir Henry Birkin that year). There were strong rumours the race was fixed from poor pit work, but Birkin managed to finish third. During the race whilst filling up the car with fuel he burnt both his arms on the exhaust. One witness account states that the Italians had removed pit equipment including a funnel that made filling the car with fuel more hazardous. A few weeks later he was back in London during mid-summer. He began suffering with flu like symptoms and became listless. Dr Dudley Benjafield, a fellow driver, was consulted and initially thought he was going into a bout of depression but noticed the dressings on his forearms. He discovered they were for burns and wanted to get him admitted into medical care for potential blood poisoning.

Birkin reluctantly agreed and was admitted to the Lady Caernarvon Clinic where he died on the morning of 22nd June. W.O Bentley described Henry Birkin as, ‘a magnificent driver, absolutely without fear and with an iron determination, who while there was anything left of his car continued to drive it flat out and with only one end in view.’ Either way, he was killed by blood poisoning prematurely ending the career of another one of the best known and most accomplished British drivers of the day.

The supercharged Bentley would eventually be immortalised in print as the personal car of choice of James Bond 007, who according to his creator Ian Fleming drove it with, ‘an almost sensual pleasure’. In the early days of his motor racing, money was never an issue for Birkin but later on the cost of developing his blower Bentleys consumed most of his family fortune, with his quest to race at every opportunity it could be argued also cost him his life.

Order your copy of Motorsport’s Military Heroes here.