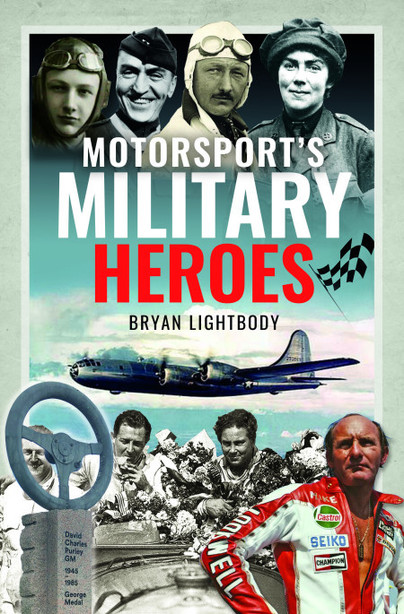

Author Guest Post: Bryan Lightbody

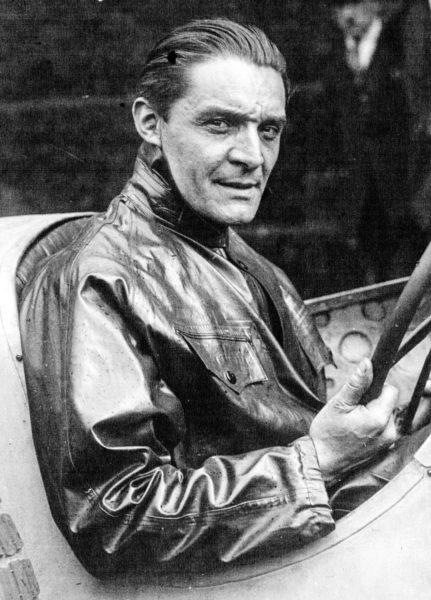

This second blog of the D-Day commemorative period, is a very abridged overview of the amazing life of Captain Robert Marcel Charles Benoist, French L’Armee de l’air pilot in WW1 and Special Operations Executive Agent WW2. He waqs a tenacious racing car driver during the interwar period, born in in Rambouillet outside of Paris.

There are many facets to the life of Robert Benoist – Grand Prix champion, Le Mans winner, World War One fighter pilot and World War Two resistance hero. He was a truly remarkable character who ultimately gave his life in the service of his occupied country. Benoist’s chapter in ‘Motorsport’s Military Heroes’ is one of the longest in the book, and that is because his life was simple incredible.

Anyone like me that is fond of travelling in Europe and/or has a passion for historic motorsport may have visited the start/finish straight buildings of the old Reims/Gueux racing circuit. One of the huge concrete spectator stands being preserved by the amazing ‘Friends of Reims/Gueux Circuit’ was named in honour of this heroic son of France and bears his name in faded paint. A fitting tribute to a man who competed tenaciously on the track, and a man who was potentially betrayed to the Nazis during World War Two by his own brother, or a perhaps by another famous SOE agent.

In the summer of 1913 Robert Benoist and some of his friends from the local cycling club decided to ride to Amiens to watch the ‘Grand Prix de L’Automobile Club de France’. The race was won by Peugeot but one of the other principle marques that came close to victory was Delage, who would become pivotal in Benoist’s racing career. Benoist returned home telling all who would listen that he would one day race for Delage.

However, in August 1914 France and Germany went to war against each other putting Benoist’s ambitions on hold, for what it turned out to be five years. He was due to be called up into the 131eme Regiment Infanterie, but because of working for mechanical company Unic who were building military trucks, he didn’t get drafted until August 1915 when he was sent to become a pilot in the newly formed L’Armee de L’Air. For many the thought of flying above battlefields in a fragile machine constructed of wood and canvas seemed very hazardous, despite the experiences of trench warfare, but to Benoist it was another adventure. He qualified as a pilot with the rank of corporal in November 1915, but it was not until April 1916 he was deployed to the 50eme Escadrille near Verdun. From there he flew reconnaissance missions for the French artillery and was promoted to sergeant in May. He served throughout the conflict.

After the war, like thousands of men across Europe he did not return home to a hero’s welcome and for 18 months he failed to find a job. He did not want to return to being a mechanic, he wanted to be a racing driver. In line with his lifelong tenacity he wrote to all the major car manufacturers across France offering his services as a test and racing driver based around his mechanical experience and knowledge, and his wartime contribution. It was early in 1921 that he received a reply from a little-known marque called De Marcay whose facility was based on the Avenue de Suffren in Paris. Their basis had been in manufacturing aircraft, but now they produced an 1100cc cyclecar and wanted someone to test it. It was the opportunity he had been waiting for, a step onto the first rung of the ladder of the growing automotive manufacturing and racing industry.

De Marcay had found themselves a competitively priced daredevil who would help eventually help promote their products in racing and beginning by conducting test runs through the streets of the Ecole Militaire district of Paris. Benoist made his racing debut in the summer of 1921 entering the Paris to Nice trial, a test of endurance for both the car and the driver. He finished a very commendable eighth overall which was a performance significant enough to attract attention.

During that same summer of 1923, Delage decided that they needed to establish their place more firmly in Grands Prix having lost out to Duesenberg in 1921, and Fiat in 1922. Despite significant investment in development in 1923 with new expertise and expense in research and development, they again lost out to another marque, this time it was Britain’s Sunbeam and legendary driver Major Henry Segrave.

In 1924 he was approached by Delage, the team Benoist aspired to drive for, it was a dream come true and he agreed pretty much on the spot. And unlike modern Formula One teams Benoist and his new team mate Rene Thomas soon became very good friends.

He took Benoist under his wing coaching him through the spring of 1924 in the art of driving the much larger competition vehicles. In August 1924 Delage were ready for the Grand Prix de l’ACF at Lyons, a fourteen-mile circuit on public highways.

Twenty-two cars entered the race, including Fiat, Alfa Romeo, Bugatti, Delage and Sunbeams, and an illustrious line up of drivers including Antonio Ascari, Enzo Ferrari, Guiseppe Campari, Kenelm Guinness and Henry Segrave. Benoist was now racing in the big league. In an event packed race, he showed his ability early on by placing third.

Benoist raced in the topflight for the next ten years.

Benoist won a hill climb, when close to the finish line he spun his car, and instead of trying to turn it round he engaged reverse and crossed the line backwards. This highlighted his quick thinking that would become crucial as he entered a new world a dozen years later, when recruited to the British Special Operations Executive.

The Delage was the best car of the 1927 season, and probably with the best driver in Benoist. He won four of the five Grands Prix, only missing out as Delage chose not to compete at Indianapolis, and at the end of the season he was declared ‘World Champion’ by the French press as there was only a world championship and not a separate driver’s championship. At the end of 1927 he was awarded the ‘Chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur’ in France, the same as a UK knighthood. For a humble gamekeeper’s son he had done quite well for himself.

Benoist became a full time Bugatti employee in 1934, but the 1934 season would be ultra-competitive with the German government supported entry of Mercedes. Taking on the position of competition manager and head of the Parisian Bugatti showroom, Benoist and Jean Bugatti were forced to conclude they didn’t have the resources to be competitive in Grands Prix. They chose to focus their efforts solely on Le Mans success.

The first attempt to win at Le Mans was thwarted by industrial unrest, so the first real attack at it was to be 1937. Early on the race there was a hideous seven car pile-up that resulted in two drivers being killed, one instantly. This was because the race was dogged by bad weather. Eventually Benoist himself driving took the win with co-driver Jean-Pierre Wimille, driving 2043 miles over 90 miles more than the previous record, and they put Bugatti back on the map having had two seasons where the Germans stole the limelight.

The Munich Crisis of September 1938 forced France to call up their reserve military officers with Benoist ordered to report to Toulon and a return to the L’Armee de L’air. But the tension eased, and he was demobilised late in 1938. He returned to Bugatti and managed the win at Le Mans in 1939, but almost immediately he was returned to uniform but too far away from any ‘action’ for his own appetite. Pulling some strings he got himself near to Paris, and closer to any action.

September 1939; war began, and everyone’s lives changed forever, the end of the ‘20 year truce’ that Marchel Foch had named the Treaty of Versailles had come to pass. Europe was at war. France was invaded, the British Expeditionary Force was trapped at Dunkirk and the Germans had simply advanced around the Maginot Line to enter France.

Benoist was in uniform and pushing papers around a desk waiting for action. Eventually he was given orders to leave the airfield at Le Bourget and head to Blois. He was given permission to use a Bugatti type 57 supercharged sports car. Before arriving at Blois he was given new orders to head to an airfield close to the Pyrenees near Tarbes. Benoist was intercepted by German forces, and when he had the chance he made a break from an enforced convoy and sped off along a side road and evaded capture. May 1942 Robert Benoist was recruited into the growing French resistance by Special Operations Executive agent, and fellow pre-war racing driver Willy Grover-Williams.

Benoist was involved in resistance operations before he came to England in August 1943, and also a dramatic capture and escape, which resulted in one particularly noted incident following the German’s capturing his brother Maurice.

Robert Benoist was spotted by SD officers in the street who were travelling in a car. Initially, as the car pulled alongside him he ignored the calls of his name, but after they persisted he knew he had to respond to the calls of, ‘Bonjour, Monsieur Benoist’. He claimed they had the wrong man, but the German officer continued to engage him, as he did so Benoist became aware of two men behind him. He was then bundled into the back of the car and was hemmed in by men either side of him.

The car was a Hotchkiss and it was tight for space, so much so that to be comfortable he placed his arms across the back of the seat, where he discovered he had access to extended leather straps that opened the rear doors. He calculated that at the right moment in a corner he could pull on a strap, open one of the doors, push a captor out and initiate his own escape. He was making calculations in his head as to where he would get the best opportunity as he knew where they’d be going, he envisaged the Arc de Triomphe as they cornered through it, but also considered it was so open he’d be an easy target to get shot. Fortune then turned in his favour, the driver made an unexpected tight left turn into rue de Richelieu. With the lurching motion Robert Benoist seized his chance and pulled on the strap to the right, the German on his right was caught unawares and Benoist heaved him out of the car and onto the road going out of the car with him. The German broke his fall as they hit the cobblestones, and Benoist was up in seconds and running taking to back streets and alleys to get away, leaving the Germans in a shocked daze.

In September 1943 in England he was given a three-week training course on the use of explosives, time that additionally allowed the interest in him in Paris to dissipate. The intention was for him to conduct demolition of electricity supplies near to Nantes. Robert completed a second training course for returning SOE agents, and at 47 years of age he impressed his staff and fellow students on his courses. He was given an emergency commission as a Second Lieutenant on the British Army General List, and in early October he began briefing for his return mission.

Benoist conducted operations between October 1943 to January 1944. Having escaped the Germans on a number of occasions he came close to being killed during an air raid on London in February 1944. He met Noor Inayat Khan once in London, during the winter of 1944 Robert also crossed paths with Violette Szabo.

He was instructed to lead the operations in Nantes and not to engage in resistance in Paris until after D-Day. He returned in March 1944 landing south-west of Paris then travelled into the city and eventually gained a vehicle to travel to Nantes.

His real destructive handiwork began on May 16th with the explosive demolition of electricity pylons supplying Nantes, it took seven days for them to restore the power whilst the city was disabled. Then four days later Benoist and his crew did it again. On June 1st 1944 the first BBC code was broadcast that put the resistance teams on standby for hitting the telephone lines and the railways. On the evening of June 5th the invasion message was broadcast. That night, groups went into action on telephone lines, railways, felling trees onto roads and blowing up bridges. Nine hundred and fifty of a planned one thousand and fifty resistance attacks went ahead across France. By mid-June after the Allies had established their Normandy bridge head, Robert Benoist returned to Paris.

Sadly, he was captured. Handcuffed, Robert asked to use the toilet, where he managed to free himself from one cuff. He tried to escape out of the window but the SS broke in and dragged him back through the window. He was taken to the German intelligence building in the Avenue Foch. Methods had changed and he was not brutalised and was frequently questioned in front of other suspects.

On August 8th Robert Benoist was taken from his cell with others he knew from SOE, male and female, ready for the move to Germany. Two of the women there were his radio operator Denise Bloch and Violette Szabo, who Benoist was certain betrayed him. The train was a ‘who’s who’ of SOE agents, resistance members and operatives within the ‘lifeline’ organisation for downed pilots. The men would end their journey at Camp Neue Bremm an SS transit camp where they would receive their first bout of brutal treatment, while the female agents were taken to Ravensbrook camp.

The men had up to three nights at this camp before being placed back into transit in slightly better railway trucks to be transported to Buchenwald. They found themselves heading into some woods then being shunted into a heavily defended compound, the high fences topped with barbed wire. It was noted the regular Wehrmacht guards had now been replaced by the SS.

Thirty-seven men described as the ‘Robert Benoist’ group by the authorities who were SOE agents entered Buchenwald in August 1944. Only five of them would survive. On Saturday 9th September Robert Benoist and fifteen other prisoners were summoned across the personal address system who had been singled out for ‘special treatment’. They would be executed by slow strangulation. Buchenwald had no gas chambers but did have a crematorium to dispose of bodies. Polish orderlies reported on Monday 11th that the sixteen were still alive but had been badly beaten. By Monday night they were dead, executed by slow strangulation. Death had finally caught up with Captain Robert Benoist.

Following the German surrender, a memorial service was held on May 29th 1945 at the church of St Pierre in Neuilly-sur-Seine in memory of French war and racing hero Robert Benoist.

Benoist was mentioned in dispatches in November 1945 as citations and awards were decided upon for the hundreds of SOE agents who had lost their lives. The French motor racing fraternity named several monuments in honour of Robert Benoist such as the grandstand outside Reims. Captain Robert Benoist is recorded on the Brookwood Memorial in Surrey, Britain as one of the SOE agents who died for the liberation of France. One of France’s greatest sons, and arguably France’s first motor racing world champion, he had thrown his all into becoming a racing driver, but twice gave his all and ultimately his life in the cause of the liberation of his country, with commitment and without fear.

…………………………………………………………………….

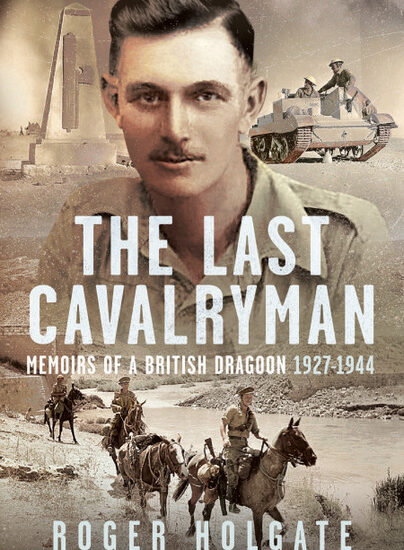

Order your copy here.