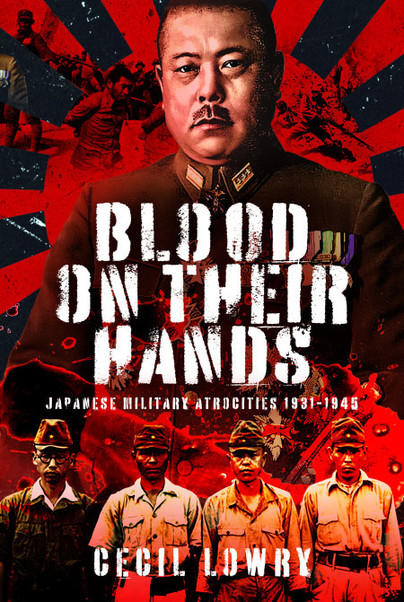

Author Guest Post: Cecil Lowry

Today (15th February) marks 82 years since the British colony of Singapore fell to the Japanese invasion forces. On that day, my father along with around 137,000 other Allied soldiers, sailors and airmen were taken prisoners of war. Around 2,500 civilians were also interned in Changi jail. One out of every four of these men and women were to die of starvation or ill-treatment during their captivity.

For three years, my father was a slave labourer on the infamous Thai/Burma Railway, (known as the Death Railway) where, along with many of his colleagues he was tortured and abused by Japanese and Korean guards daily. They were robbed of their possessions as well as their dignity, working night and day in atrocious conditions.

The psychological and physical wounds suffered by the victims of Japanese military cruelty have continued to haunt their families (including my own) right up until today.

Whilst many people may shrink at the contents of this book, I would argue that those who do not remember the past are condemned to relive it.

It has been estimated by historians that from the invasion of China in 1937 to the end of World War II, the Japanese military regime murdered nearly 3,000,000 to over 10,000,000 people, most probably almost 6,000,000 Chinese, Indonesians, Koreans, Filipinos, and Indochinese, among others, including Western prisoners of war. They argue that this democide was due to a morally bankrupt political and military strategy, military expediency and custom, and national culture.

Most people will agree that wars should be conducted in such a way that non-combatants are protected, and that military discipline is such that casualties are kept to a minimum. The Japanese rode roughshod over this agreement as you will discover in this book.

The Japanese original concept was of a South-East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere that would liberate Asian countries from their European colonial rule. This new sphere would, according to their imperial propaganda:

‘Establish a new international order seeking co-prosperity for Asian countries and free them from Western colonialism and domination.’

Japanese nationalists, however, saw it as a way to gain resources that were scarce in their homelands. They coveted resource-rich western colonies such as British Malaya, Burma, American Philippines, French Indo China and the Dutch East Indies. In reality, it was a front to completely control the countries they were to annex in which puppet governments, manipulated local populations and economies for the benefit of Imperial Japan.

During their attempt to create this Greater South-East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere during the 1930s and early 1940s, the Japanese were guilty of carrying out numerous atrocities across the countries they invaded. Many thousands of innocent men, women and children perished at the hands of a brutal military machine.

For three and half years, my father was a slave labourer on the infamous Thai/Burma Railway, (known as the Death Railway) where, along with many of his colleagues he was tortured and abused daily. They were robbed of their possessions as well as their dignity, working night and day in atrocious conditions.

Allied prisoners of war in Japanese hands were housed in filthy conditions, with many starved to death and others reduced to walking skeletons. One out of every four of these men was to die of starvation or ill-treatment during their captivity.

It was not until the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in early August 1945 that, at 28 years of age, my father realised that he might see his family again and have a life to look forward to. He was one of the lucky ones to survive. My very existence depended on the dropping of those two bombs in August 1945 – there by the grace of God. Along with thousands of other prisoners of war, he had been sentenced to death by the Japanese if the Allies ever invaded the Japanese homelands towards the middle of 1945. This edict was sent out in an order issued by the Japanese High Command to all prisoner of war camp commanders. A copy of this actual order was found in the safe in one of the camps in Formosa after the war and is now in a US archive.

By early March 1942, the Japanese had interned over 140,000 Allied prisoners of war in camps scattered all over the Far East. Around one in four of them were to die of disease, starvation, and massacre, before the war ended in August 1945. Over 130,000 civilians were also interned mainly colonial officials and their families, employees of European companies and the families of Allied servicemen. Once again one in four were to die of disease, starvation, and massacre.

Military historians have estimated that the number of deaths perpetrated or condoned by the Japanese military through massacre, human experimentation, starvation and forced labour during those fourteen years, range from anything from three to fourteen million.

Eminent historian Norman Stone said that during the war, the Japanese were:

‘A talented people led by maniacs who knew perfectly well that the war would end in disaster but who were determined to keep their honour intact to the final gruesome suicidal point.’

As an author, I will not shy away from the suffering caused by the Japanese military to innocent people, before and during the Second World War. The unsavoury facts, no matter how horrific they appear to be, must be put into the public domain.

Order your copy of Blood on Their Hands here.