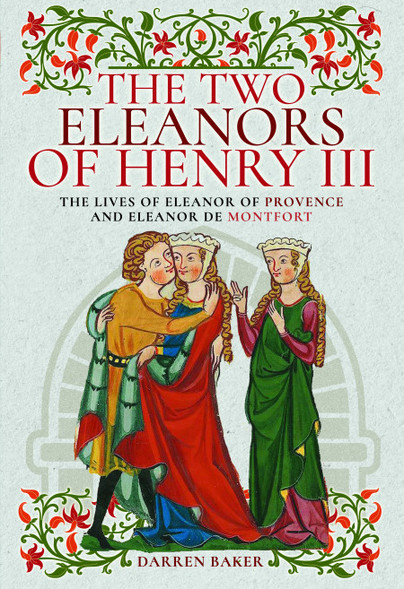

Author Guest Post: Darren Baker

Eleanor of Provence and the Founding of Parliament

There is no cornerstone or date when parliament was founded. It arose in early thirteenth-century England because Magna Carta imposed limits on the monarch’s authority. From then on, if the king or queen wanted money or men for war or whatever, they had to summon assemblies of barons and clergy and ask them for a tax.

The first king to rule under this new arrangement was Henry III. In January 1236, he summoned such an assembly to Westminster, first to witness his wedding to Eleanor of Provence, and second to discuss the affairs of the realm. Heavy rains flooded out Westminster, so the assembly met at Merton Priory, close to today’s Wimbledon.

At the top of the agenda was a new codification of the kingdom’s laws. By discussing and passing new statutes, this assembly became the first parliament in the sense of acting as a legislative body. It was no coincidence that in the same year the word ‘parliament’, meaning ‘to discuss’, was first used to describe these assemblies.

The next year, in 1237, Henry summoned parliament to London to ask for a tax. He needed money to pay for his wedding and various debts he had accumulated. Parliament grudgingly agreed, but tacked on conditions for how the money was to be collected and spent.

It was the last tax Henry got from parliament for decades. Every time he asked, he found their conditions more intrusive and ebbing away at his authority. In 1248 he had to remind his barons and clergy that they lived in a feudal state. They could no more expect to tell him what to do while denying the same voice to their own subjects and communities.

By this point the concerns of ‘the little guy’––knights, farmers, townsfolk––started resonating in national politics. They wanted protection from their lords, the sheriff, wanted cheaper and more efficient justice. They believed that Magna Carta should apply to all people in power, not just the king, and Henry agreed.

In 1253, Henry went to Gascony to put down a revolt against the governor he had appointed, Simon de Montfort. War seemed imminent, so he asked his regent to summon parliament to ask for a special tax. The regent was the queen, Eleanor of Provence. She was pregnant when Henry left and gave birth to a girl. Receiving her husband’s instructions a month later, she convened parliament, the first woman to do so.

Parliament met as summoned and although the barons and clergy said they would like to help, they could not speak for the little guy. So Eleanor decided to reach out to them. On 14 February 1254, she ordered the sheriffs to have two knights elected in each county and sent to Westminster to discuss the tax and other local matters with her and her advisers.

It was a groundbreaking parliament, the first time the assembly met with a democratic mandate, and not everyone was happy about it. The start was delayed, rather prorogued, because some of the senior lords were late in arriving. The tax was not approved because Simon de Montfort, who was still angry at the king over his recall as governor, told the assembly he did not know of any war in Gascony.

In 1258, Henry was massively in debt and gave in to parliament’s demands that the kingdom undergo reforms. A constitution was devised, the Provisions of Oxford, under which parliament was made an official institution of state. It would meet every year at regular intervals and have a standing committee working together with the king’s council.

Two years later relations broke down between Henry and radical reformers led by de Montfort. The battleground was parliament and whether it was a royal prerogative or instrument of republican government. Henry came out on top, but in 1264 de Montfort led and won a rebellion. He turned England into a constitutional monarchy with the king as a figurehead.

In January 1265, de Montfort summoned parliament and for the first time on record the towns were invited to send representatives. This was Simon’s acknowledgment of their political support, but because England was in a revolutionary state, governed by an authority other than the monarch, later historians in the Victorian era decided this was the starting point of democracy.

Here was a glimpse at the future House of Commons, they touted. The three decades of parliamentary evolution before that were conveniently ignored, in particular Eleanor of Provence’s contribution. The reason was clear enough. The Victorians were looking for a distinctly English stamp on the history of democracy to rival the French and their revolution of 1789.

Unlike Simon, Eleanor had no ties to England before her marriage. Since the strength of his rebellion was due in large part to anti-foreigner sentiment, she too was subjected to the violence that helped propel him to power. The Victorians, who rolled their eyes at the excesses of the French Revolution, decided the less press she got the better.

You can order a copy here.