Author Guest Post: Martin Barratt

Fine margins – Flying on Ops in 1943

For the vast majority of people, it’s probably fair to say that lockdown was a time of uncertainty, stress and also a period of enforced incarceration. The things that we all once took for granted such as trips to the pub, holidays abroad, gatherings with family and friends, even just daily freedom of movement were suddenly taken away from us and a new unfamiliar regime put in its place. Those of us who own small businesses also found ourselves presented with the additional headache of having to try and ensure our business could function with remote-working and all the challenges that that brings. For others, myself included, we also had to cope with not being able to see relatives in care-homes whom we were unable to visit. I was only able to see my mother twice in over a year before she died – suffice to say the care home staff were magnificent.

In all of this I decided to use the time to draft the manuscript of my new book, The Greatest Escape, and without for a moment wanting to remotely trivialise the experience of allied POWs like my father, it did bring it home to me just how much we take those aforementioned freedoms for granted. As well as running the family business during business hours, lockdown at least gave me the chance to switch off and focus my efforts on writing – particularly weekends. The monotony of hours, days and weeks spent indoors channeled into something that at least felt productive.

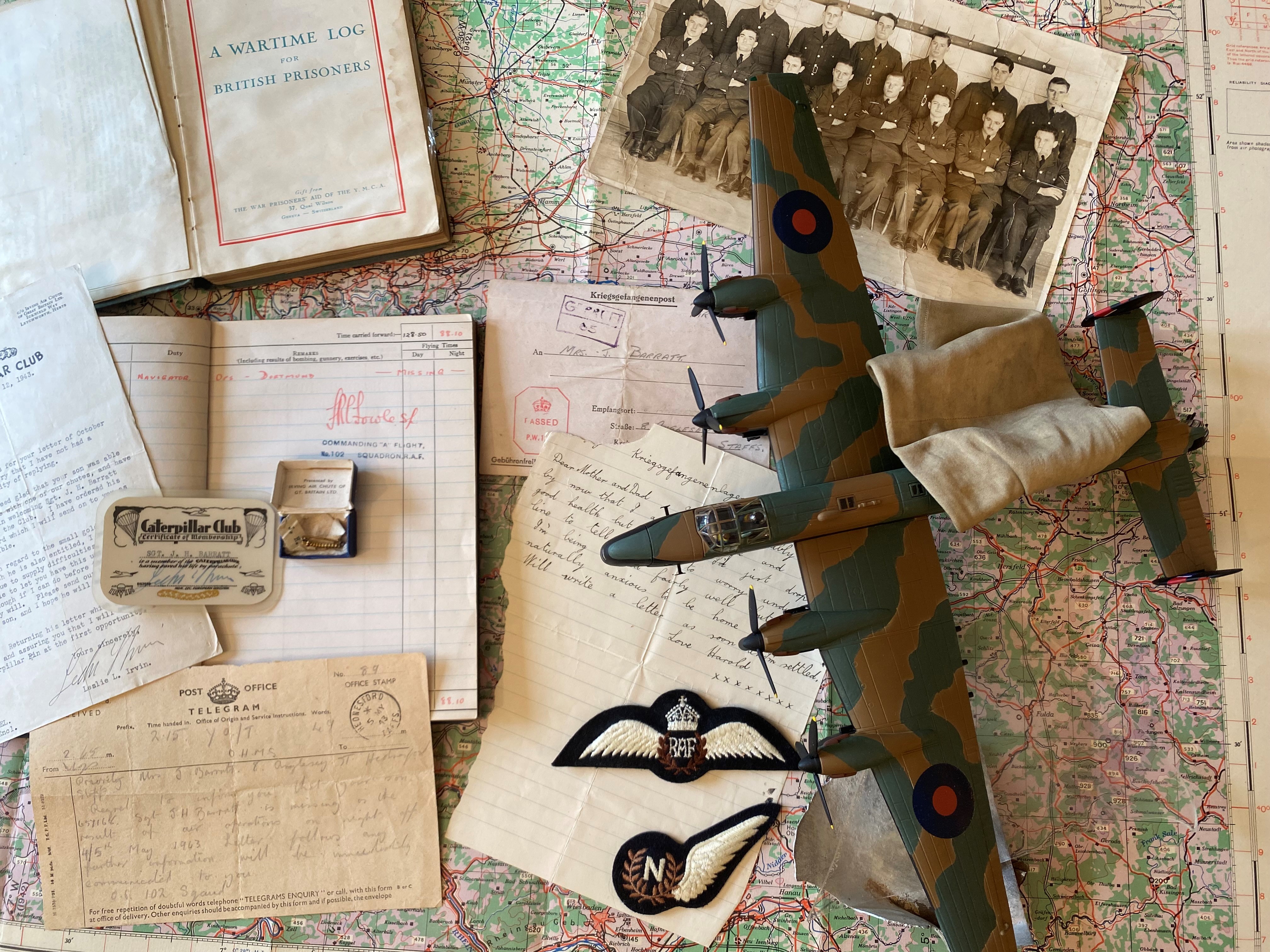

The book is about my late father, a navigator in 102 Squadron, and his time training, on ops and then as a POW after he was shot down in May 1943. The culmination of over 24 years of extensive research into his life and into the crew of my father’s Halifax, JB869 ‘H’ Harry, it tells their story for the first time drawing on an archive of personal papers, photographs, and letters – many being published for the first time.

A frontline squadron of 4 Group, 102 Squadron was based at Pocklington Airfield near York from late 1942 and, equipped with the mighty four-engine Handley Page Halifax, the Squadron and its crews were destined to become a major participant in the Battle of The Ruhr. Taking place from March to July 1943 the Ruhr campaign was the RAF’s main offensive (at that time) against the industrial heartland of Germany and one that saw the young aircrews of Bomber Command flying deep into Germany to attack some of its most heavily defended targets including Essen, Duisburg, Dortmund, Frankfurt, Cologne and Wuppertal. Over 1000 aircraft from a range of Squadrons were lost during the battle, claiming the lives of some of the Commands best and most experienced crews and ensuring thousands of men, who managed to bail out, would spend the rest of the war as prisoners of the Reich. In fact, the squadron would suffer the second highest losses of any frontline operational squadron within Bomber Command during WW2.

The late afternoon of Tuesday 4th May: The crews of 102 filed into the briefing room at Pocklington to be told their ‘target for tonight’, the doors smartly locked behind them and an armed guard placed outside the door. In a matter of hours, the crew of Halifax JB869 ‘H’ Harry, my father’s aircraft, would be heading towards Dortmund with 595 other aircraft in what was, up to that time, the largest four-engine bomber road of the war and the first major attack on the city. For pilot Bernard Happold, bomb aimer John Baxter, flight engineer Gordon Bowles and mid-upper gunner Duncan McGregor it would be their final night on earth. For my father, wireless-op John Brownlie and rear gunner Tommy Jones it would end with their tumbling into the night sky from their stricken bomber, a hard landing and the start of 2 years in captivity.

My father was to survive a near lynching on the ground followed by incarceration at Stalag Luft I and then Luft VI at Heydekrug where, with almost 900 others, he would be locked in the hold of an ageing coaler, the SS Insterburg, and transferred to the notorious Stalag Luft IV, Gross Tychow. The camp was to become a byword for cruelty – on arrival prisoners were shackled together and forced marched to the camp, beaten, kicked and clubbed by German Kriegsmarine who jabbed them with bayonets, hit them with rifle butts and set their dogs on the bloodied and battered column of men.

For my father and wireless op John Brownlie the end to their war would only come after one final ordeal – the forced march across a frozen Germany in the bitterly cold winter of 1944/45, away from advancing Red Army troops. With no winter clothing, poorly- provisioned, suffering from dysentery, near starvation and with swollen and blistered feet many men finally succumbed to the appalling conditions and either froze to death during the night or – unable to continue – fell by the wayside and were shot where they lay.

My father rarely spoke of the darker episodes of his time as a POW, only about his two brief escape attempts when he managed to get out of the camp, and some of the more humorous episodes but I was lucky enough to speak to veterans who knew him, were in the camps with him and were with him during some of the grimmest of days. I also had the benefit of a unique archive of his POW letters home, every single one kept safe by my grandmother and which provided an invaluable diary of his movements during his time as a ‘Kriegie’.

Writing the book was daunting at first – condensing the reams of research material, raid reports, transcripts, letters, and conversations held over nearly a quarter of a century into what I hope will be an interesting and informative narrative. Some chapters came more easily than others but overall, it was a feeling of the flood gates opening after so many years of on-off research and there were many times when I recall that my fingers could not keep up with what my brain was thinking and, as any author will tell you, that’s a boon when the writing flows that easily. At key points in the story I was right back there in the living rooms of the veterans I was lucky enough to meet over the years – Bill Pattison from 102 Squadron sticks in the mind as do numerous lengthy telephone calls with Cal Younger, Percy Carruthers, Tom Wingham and Bill Brownlie (son of my dad’s W/Op John) and John Andrews (cousin of my father’s friend and pilot Bernard Happold who so bravely gave his life so that my father and others had a chance to bail out ).

The driving impetus was to tell a story of seven young men that has remained hidden for decades, it is one that is well worth telling and after 24 years it allowed me to keep the promise I made to the relatives of Bernard Happold, John Baxter, Gordon Bowles and Duncan McGregor – the members of my father’s crew who didn’t return – to tell their story and to ensure their sacrifice is not forgotten.

‘The Greatest Escape – The Story of a Bomber Command Navigator’s Survival in Nazi Germany’, will be published on 30th April 2023 and is available to preorder here. (A percentage of my share of the royalties from the book are going to the RAF Benevolent Fund in memory of my father and his crew).