Author Guest Post: Philip Hamlyn Williams

Preparing for D Day

Preparations for D Day surely began with the evacuation of Dunkirk; if Hitler was to be defeated, an invasion would be required. An early date for the start of preparations for D Day is evidenced by the Pluto and Mulberry projects where a young Naval officer, Louis Mountbatten, was tasked with the identification of issues to be addressed. One such was just how an invading army would be equipped.

On 25 June 1940 two men met by chance in the War Office. They had both served in the Army Ordnance Corps during the Great War (The AOC became the RAOC in 1918). Colonel Bill Williams had set up the Army Centre for Mechanisation at Chilwell outside Nottingham and had since April been Director of Warlike Stores on a six month probationary period. Colonel Clifford Geake had served in the British Expeditionary Force (‘BEF’) and would take command over Clothing and Stores. Working initially under the watchful eye of more senior officers, they had the job of supplying the army with all it needed except for food and fuel – the responsibility of the Royal Army Service Corps. They would be joined by officers and men who had fought in the Great War, those who had enlisted since and vastly more from civilian life – altogether some 250,000 men and women of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps.

So much effort had gone into the preparation of the BEF and now, with so much left behind in France, they had to start over again. There was an imminent threat of invasion and in due course there would be other theatres of war to be supplied. To add to all of this the RAOC, still designated a non-combatant corps, was looked down upon by fighting sections of the army many of which wanted their own bespoke supply organisation. There were battles to be fought.

Motor transport was well in hand at Chilwell with depots at Derby and elsewhere coming on stream. Warlike Stores were handled at Greenford, but also Old Dalby in Leicestershire and Donnington in Shropshire where a vast depot was being built to take over from Woolwich and the ever present danger of German bombing. Small arms were handled at the 19th century barracks at Weedon and ammunition in many places around the country including a vast subterranean depot outside Bath. Clothing was based in the former pickle factory at Branston and general stores at Didcot. A brand new multitask depot was planned at Bicester specifically for D Day.

Equipment needed to be produced. Vickers formed the backbone of gun and tank production from its experience in the Great War. Lord Nuffield had undertaken the development of a new tank, the Cromwell. These were joined by Vauxhall’s Churchill tank. All the British motor companies came up with their war purposed vehicles together with anything from aircraft to tin hats and were supported by companies like Lucas, Dunlop and Smiths. Signals equipment was manufactured by the adolescent radio industry. Medicines and healthcare products came from the infant pharmaceutical companies. Ammunition and gun production became a vast industry surrounding the chemicals giant ICI and the network of Royal Ordnance Factories which had been resurrected and enlarged upon from that set up by Lloyd George in the Great War. Echoes of that earlier war came with the mass production of boots in and around Northampton which had long been a centre of boot making. Clothing although based at Branston came from the textile manufacturing areas of Yorkshire and Lancashire. For a seaborn invasion provision was made for changes of clothing should soldiers become drenched in seawater on landing.

As Churchill knew all too well, without America, there could be no D Day; quite simply this island, even with all the resources of Empire, couldn’t compete with the might of Germany. In terms of arming the army, this meant that we needed many tons of American weaponry, not least, it has to be said, since British motor companies were manufacturing many thousands of aircraft and had been since the shadow factories had been set up in the thirties. So we had Sherman tanks and Willis Jeeps as well as heavy tank transporters, and caterpillar tractors in anticipation of the devastation in the towns through which the invasion would need to pass. Hobart’s funnies was the nickname given to a whole range of tank adaptions made both in the factory and in REME workshops. The Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers had been spun out of the RAOC in 1942.

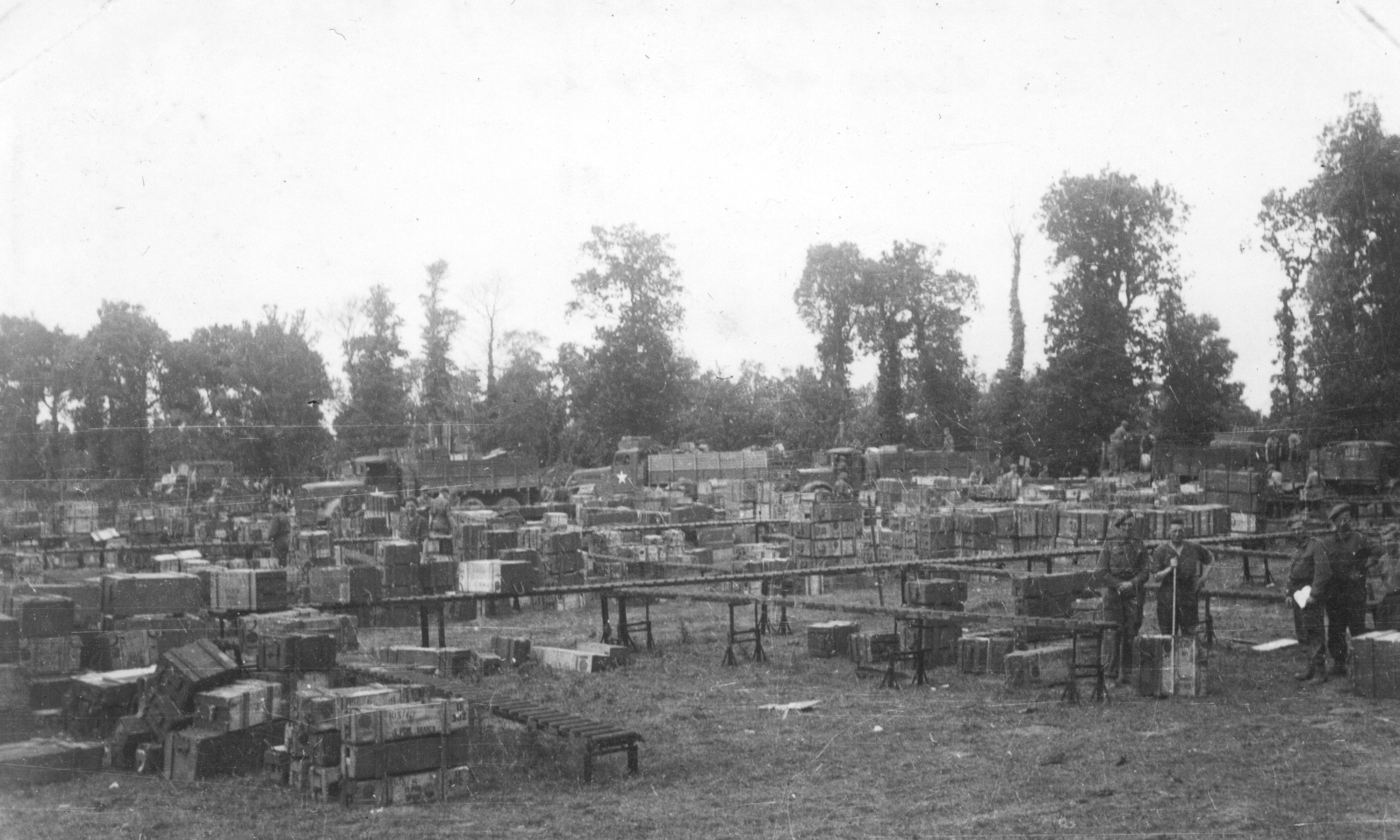

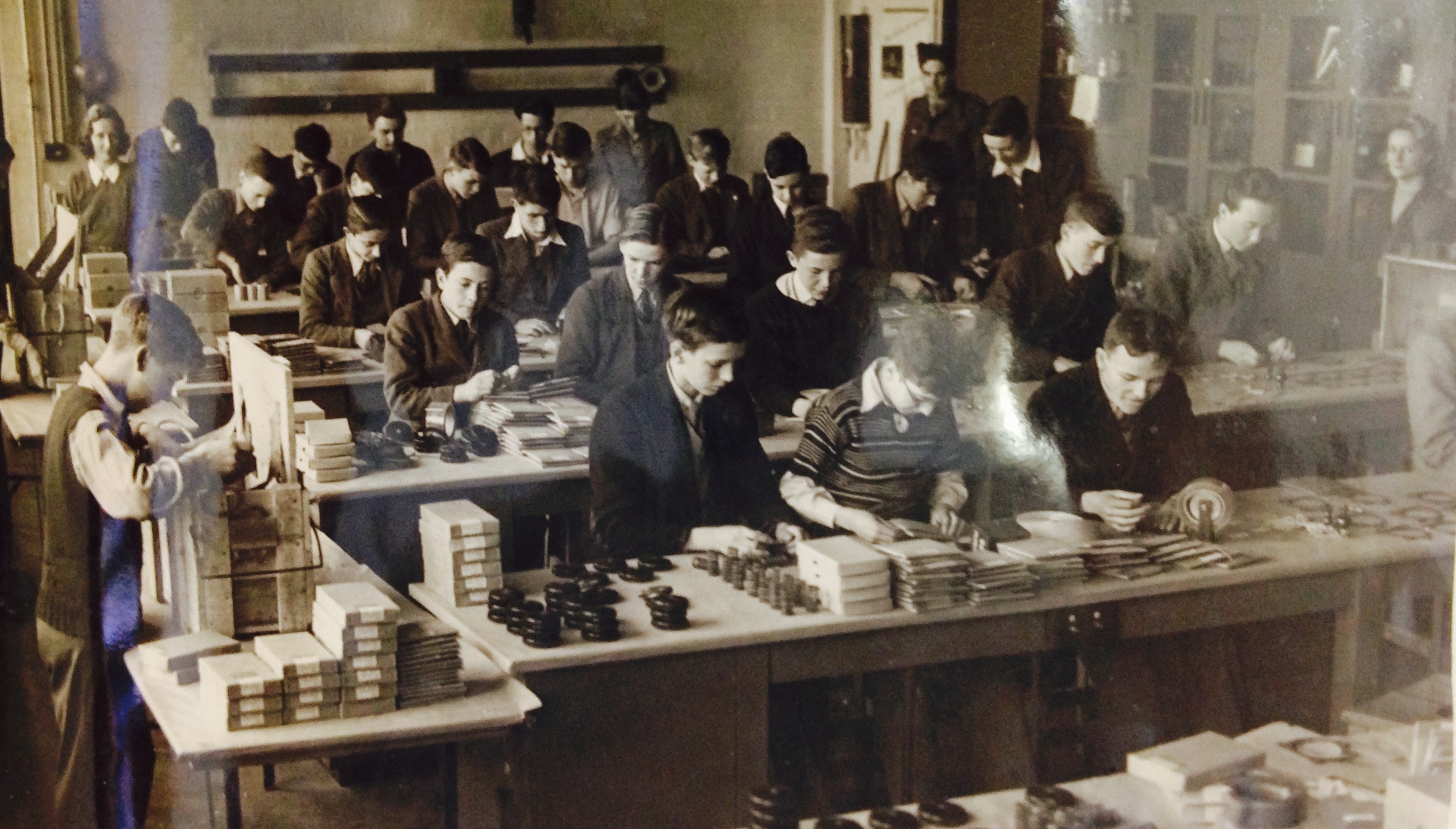

Just how do you get what is needed to an invading force? Experience of earlier invasions of North Africa, Sicily and Italy was analysed and answers proposed identifying three stages of invasion: on the beach, on the first advance inland and on the setting up of the first base depot. Parts identified for each stage had to be packed for protection, but also for clear identification. A system of packing was devised that could be used in depots and also by manufacturers. Volunteers, including school children, helped with packing millions of items. The roles of particular depots were redefined, additional storage was put in place by Dickie Richards who returned from the Middle East, swapping posts with Geake, to oversee Clothing and Stores and to hold together the interface between depots and field operations.

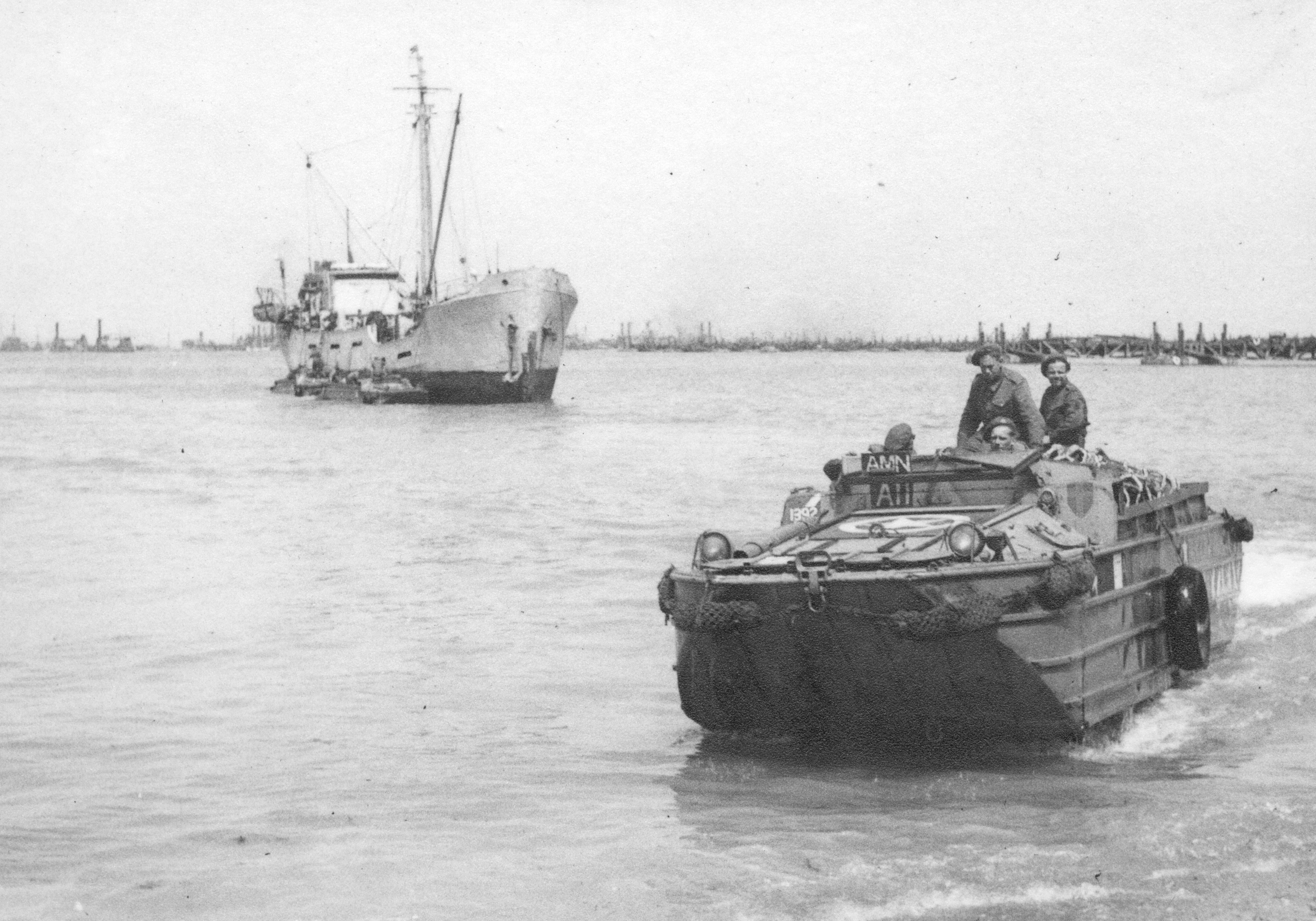

The next question was how to get the stores from the ship to the fighting man. There would be some mechanical help from DUKWs for example, but the majority of the work would demand manual handling and thus men able to carry loads under fire. Package sizes were selected to be capable of being carried, but the men needed to be fit. In the summer of 1943 a training programme was introduced for RAOC men to make them both physically fit but also capable of fighting. The RAOC had ceased to be classified as non-combatant in 1941.

With D Day approaching, the RAOC depots reported that essential spare parts were missing for vital American equipment. Bill Williams, armed with a letter of authority from General Montgomery, set out on a whistle stop tour of US factories and ensured that what was needed was sent.

Phil Hamlyn Williams has written in Dunkirk to D Day the stories of those who led the work of the RAOC for D Day, and in How Britain Shaped the Manufacturing World about the companies which made the equipment used by the British armed forces in both world wars.