Author Guest Post: Robert Gawlowski

“I am the one who broke the Enigma” – in memory of Marian Rejewski who was the first Enigma code-breaker

Polish cryptologists found that Germany used Enigma in the late 1920s, almost a decade before the outbreak of the Second World War. Their intuition was to look for unconventional tools because traditional ways of working were simply unsuccessful. Looking for unconventional solutions, the General Staff of the Polish Army in cooperation with the University of Poznan (precisely prof. Zdzisław Krygowski) organized a cryptology course dedicated to students of mathematics. It was a way to chose three of the most talented three: Marian Rejewski, Henryk Zygalski and Jerzy Różycki.

Rejewski and two his colleagues started permanent work at the Cipher Bureau on 1 September 1932. As he recalled: ‘The beginning of work was difficult (…) we had no starting point. The encryption was done by machine and the frequency of the letters was random. If someone wanted to approach such a message in a traditional way, i.e. using the properties of language, they would quickly see that it was ineffective. Searching for regularities in such an encrypted message was simply impossible. Therefore, it was not surprising that the Germans believed that the new code was fully reliable and secure. At one point, a new circumstance arose; a clue that turned out to be ground-breaking. The representative of the French cryptology unit, Major Gustave Bertrand, handed over the documentation on Enigma during a personal visit to Warsaw at the beginning of December 1932. One day, Major Ciężki wanted to talk to Rejewski. During the conversation, the question was asked – did Rejewski have free time in the afternoon; could he come to work? Such a question in such a place must have meant something special. The request was confidential. Rejewski was not supposed to mention it to anyone, not even to his fellow cryptologists. Rejewski began his task with full commitment.

As Rejewski noted, if we have a sufficient number of messages from a given day (about eighty), then all the letters of the alphabet will usually appear in all six places at the beginnings of messages. In each place, they create a mutual, unambiguous transposition of a set of letters. Obtaining the permutation systems allowed for the reconstruction of the internal connections of the machine in just a few days. These, in turn, were the basis for building copies of the machine, which for many years allowed code-breakers to reconstruct the keys that changed every day and read encrypted messages.

Using his earlier findings and information provided by the French, between Christmas 1932 and New Year Rejewski broke the Enigma code; an unprecedented event in cryptology. It meant that the Poles were the first to explain the internal settings of the machine and, by reversing the way it operated, to indicate how to decode it. The next step was therefore obvious, ‘[i]t was only necessary to build this machine now,’ as Marian Rejewski stated.

Thanks to the results of the mathematical work of cryptologists, possession of the commercial machine and documents provided by French intelligence, it was possible to start work on building a copy of the Enigma. The AVA company, cooperating with the Polish Army, carried this out. One month after breaking the Enigma code, on 30 January 1933, Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany.

Due to the coming outbreak of World War II, Poles shared their knowledge about the Enigma with British and French colleagues. It was during the meeting in Pyry on July 1939, when Marian Rejewski and his colleagues present the way how they crack the Enigma code and gave a replica of Enigma as a present. In this way, Polish cryptologists passed a baton that allows continuing their work in Bletchley Park.

For many decades, Marian Rejewski could not tell the truth about his and his colleagues’ achievements. Coming back to Poland after World War II, where communists took power, he had to keep silent. . In 1973, when Gustave Bertrand released his memoirs, the Polish newspapers started looking for codebreakers. It was only then – many decades after the war – that Marian Rejewski, responding to an appeal in a local newspaper, could state: “I am the one who broke the Enigma. If you are interested in how I did it, please come along and I will explain all the details.”

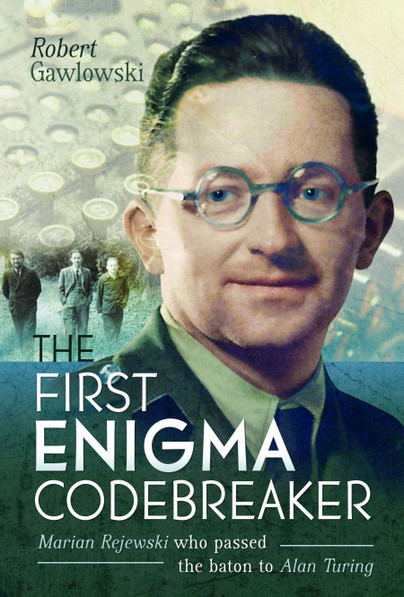

More about Marian Rejewski you will find in a book: The First Enigma Code-Breaker. The untold story about Marian Rejewski who passed the baton to Alan Turing.

Preorder The First Enigma Codebreaker here.