Author Guest Post: Stephen Browning

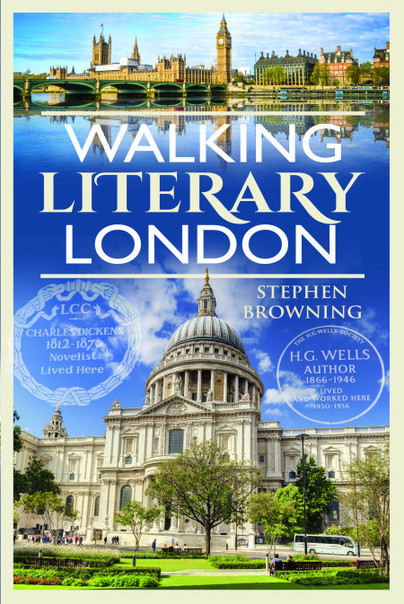

Walking Literary London

Literary London: 5 Takeaways that you may not know

Walking Literary London consists of 11 walks around the great city of London, each one unique and the result of twenty years’ exploration of this incredible place by the author. Easy-to- follow maps have been specially commissioned and there are over 80 pictures to give a flavour of the walks (especially useful if you are ‘walking’ from an armchair at home). Each chapter, or walk, contains comment and analysis as well as giving interesting facts and stories about the writers and their works. Associated historical and social circumstances are given, too.

Over 350 writers are highlighted in the book. Here are five takeaways that you may not know from the incredible London literary scene over the centuries.

- Thomas Chatterton

Just before reaching Chancery Lane tube station, on your right, is Brooke Street. Number 39, now part of an office block, was where ‘the marvellous boy’ (Wordsworth), Thomas Chatterton, poisoned himself with arsenic on the night of 24 August 1770: he was 17 years and 277 days old.

He became a romantic hero to many young people after he tried to pass off his work as that of an imaginary fifteenth century monk and poet called Thomas Rowley. He succeeded to some degree although not everyone was convinced. It was a general opinion, though, that even if the poems were ‘fake’, they had considerable merit.

‘This is the most extraordinary young man that has encountered my knowledge. It is wonderful how the whelp has written such things’

Dr Johnson, referring to the ‘Rowley’ verses of Chatterton having just been part of a lively discussion when some were read out and which he then pronounced a fraud (from The Life of Samuel Johnson LL.D, 1791, as recorded by James Boswell).

- Contemporary opinion of Shakespeare

Shakespeare was not always seen favourably by his contemporaries. Fellow dramatist Robert Greene, for example, called him ‘an upstart crow’ in his Groats-Worth of Wit of 1592 – this is probably aimed at him as a man who presumed to compete with his university-educated fellow dramatists like Christopher Marlowe and Thomas Nashe, two of the famous ‘University Wits’.

Samuel Pepys was a prolific theatre-goer and went to many Shakespeare plays, thinking some good, others not so fine. On 1 March 1662 he went to see Romeo and Juliet and said ‘it is a play of itself the worst that ever I heard in my life’…

Dr Johnson was a great admirer but did not always favour going to the theatre, saying to Boswell: ‘Many of Shakspeare’s (as Boswell spelt the name in his Life of Johnson, 1791) plays are the worse for being acted: Macbeth for instance’.

- P.L.Travers resisted Walt Disney’s entreaties for many years.

50, Smith Street, Chelsea has a blue plaque commemorating P.L. Travers (1899–1996), author of the Mary Poppins books, the fourth of which was written during her life here 1946–62. It was also here, after many years’ resistance, that she finally succumbed to the charms of Walt Disney and agreed to the filming of the tales. Although she was unhappy at the ‘sugar-coating’ of the character’s darker aspects, the film was an immense and enduring success, gaining Travers worldwide recognition.

- Strand – an important literary thoroughfare.

Strand, often known incorrectly as THE Strand, has always fascinated writers. Virginia Woolf, who knew the great streets of London intimately, was struck by its character.

Hereabouts, if we are playing the Sherlockian ‘Great Game’, is the location of the ‘worn and battered tin dispatch box’ entrusted to Watson’s bank, Cox and Co, which contains many adventures not as yet released to the public.

Charing Cross was also one of several places in London where executions took place in the seventeenth century. Samuel Pepys witnessed one on 13 October 1660. Charles II entered England on 29 May 1660 to reclaim his throne on his 30th birthday. Thomas Harrison had sat as one of the judges of Charles I. Pepys says that he went to Charing Cross to see Major-General Harrison hanged and thought he looked ‘as cheerful as any man could do in that condition.’ His head and heart were cut from his body and shown to the people whereupon ‘there were great shouts of joy’.

About two and a half centuries later, Sherlock Holmes is here, too. The thrilling end of The Bruce Partington Plans takes place in the smoking-room of the Charing Cross Hotel

Other writers who lived or spent time in the immediate vicinity of Strand include Charles Dickens, Oscar Wilde, Jane Austen, Rudyard Kipling, G. K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc, Christopher Isherwood, Thomas Hood, J.M. Barrie, John Galsworthy, George Bernard Shaw, Thomas Hardy, William Blake, Voltaire, Wilkie Collins, John Dryden and Thomas Hardy. Details are given in the book.

‘Always forgive your enemies; nothing annoys them so much’

Oscar Wilde

Here is the Adelphi Theatre. One of the greatest successes for Dickens at this theatre was an adaptation of his Christmas story No Thoroughfare which he wrote with his good friend, Wilkie Collins. It made a lot of money.

Someone else who put on plays here was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle who had similar success with The Speckled Band which premiered here on 10 June 1910. He writes that he purchased a live snake for the production – ‘the pride of my heart’, he says in his autobiography, Memories and Adventures – a feature not appreciated by all critics, one of whom wrote that it was ‘a palpably artificial serpent’; Conan Doyle was tempted to offer the critic a good sum of money to go to bed with it.

Strand becomes Fleet Street which becomes Ludgate Hill and this is where you will find St Paul’s Cathedral around which, in Pepys’ day, the booksellers set up shop.

- Oscar Wilde, Lord Alfred Douglas and ‘The Love that Dare not speak its Name’

‘The love that dare not speak its name’, mentioned at Wilde’s trial, is widely misattributed to Wilde. It actually comes from the poem, Two Loves, published by Lord Alfred Douglas in The Chameleon in 1894, when he was 24.

Preorder your copy here.