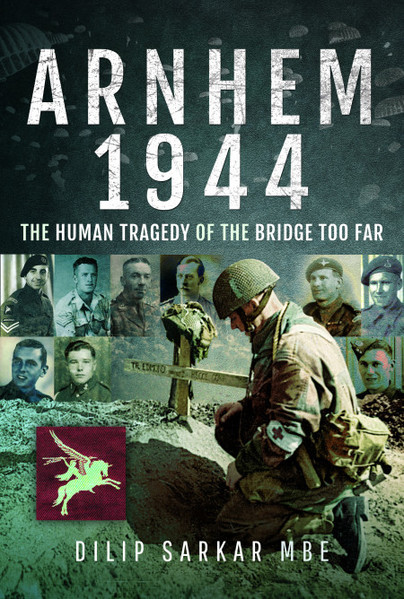

Guest Post: Dilip Sarkar MBE – Arnhem 1944: The Human Tragedy of the Bridge Too Far….

2019 saw two major Second World War Anniversaries: the 75th anniversary of D-Day and that of the largest airborne operation ever mounted, MARKET-GARDEN, Field Marshal Montgomery’s audacious plan for British, American and Polish airborne troops to seize the bridges over the rivers Maas, Waal and Rhine, and hold them pending relief from advancing ground forces. The plan was to bypass the fortified Siegfried Line and enter Germany through the back door, quickly occupying the enemy’s Ruhr industrial area – and end the war by Christmas 1944…

In the event, the furthest bridge – at Arnhem in the Netherlands – the British and Polish objective, was lost after a dreadful battle against overwhelming odds. Nobody had anticipated how swiftly and ferociously the Germans would react to this airborne assault, pouring armour and troops into Arnhem and nearby Oosterbeek, and poor weather delayed the arrival by air of British and Polish reinforcements and supplies. Lieutenant-Colonel John Frost’s men grimly hung on to the northern end of Arnhem Bridge, cut off from the rest of the 1st British Airborne Division which, having been unable to reach and relieve ‘Johnny at the Bridge’, had formed a defensive pocket around the village of Oosterbeek, some three miles or so west of Arnhem. Frost’s men held out for many days longer than was intended, but were ultimately overwhelmed. These ‘Red Devils’, however, had forged a new benchmark for courage, the last radio transmission from the Bridge being ‘Out of ammunition. God Save the King’.

Ultimately, the tanks and supporting infantry of XXX Corps, which had fought so hard to reach Arnhem Bridge from their start-line some sixty miles away, ground to a halt after relieving American troops at Nijmegen – just eight miles from Arnhem. With no chance of relief, General Roy Urquhart had no option but to evacuate what remained of his forces at Oosterbek across the Rhine on the night of 27/28 September 1944. By that time, the 1st British Airborne Division had been reduced from 10, 095 men to 2,490 – the balance of 7,605 officers and men either known to be dead or missing. According to the British historian Martin Middlebrook, 1,485 were killed, and 3,910 were either safely evacuated across the Rhine or, in the case of General Sosabowski’s Poles, withdrew from Driel to safety in Nijmegen.

Writing after the event, General Urquhart acknowledged that the ‘operation did not end quite as we intended’, that ‘losses were heavy’ but considered that ‘the risks involved were reasonable’. Field Marshal Montgomery reported that the ‘Battle of Arnhem was 90% successful’, Urquhart’s ‘magnificent stand’ having ‘held off enemy reinforcements from Nijmegen and vitally contributed to the capture of the bridge there’. Upon conclusion of the operation, the Allies were in possession of four major bridges, the Waal bridgehead later proving a vital factor in eventually crossing the Rhine and advancing to the Baltic. The swift and violent German reaction, however, was the decisive factor, the British Group of Armies in the north not being strong enough to ‘retrieve the situation… to reinforce Arnhem by road’. The British overall airborne commander, General ‘Boy’ Browning, famously said that Arnhem was ‘A Bridge too far’. Today, historian and enthusiasts get themselves in such a tiz debating whether this was the case – or not. Getting bogged down in such detail, so long after the event, however, is not for me, preferring instead to leave those discussions to the army of armchair generals out there. No, what is important to me is the human cost.

The graves of most of the British and Polish casualties suffered at Arnhem and Oosterbeek can be found today at the immaculate Arnhem-Oosterbeek War Cemetery – universally known as the ‘Airborne Cemetery’, which contains 1,774 graves. 244 of these are ‘Known Unto God’ – the story of Arnhem’s ‘missing’ being a subject all of its own. Walking around the headstones, is deeply moving. Beyond moving. Every stone represents a personal tragedy, a story to be told, and devastated loved ones even today feeling the effects of these losses. Some men died never meeting their new or unborn children, who would grow up without knowing their fathers. Other families remain in turmoil over their ancestors being missing. And so the Battle of Arnhem still reverberates down the generations, even today. Across the lane from the Airborne Cemetery is the local Dutch cemetery, in which lie various civilian casualties from the devastating battle – the youngest being two-month-old Sibilla Hendrika Snijder, killed on 18 September 1944 when a grenade landed in her cot. If that does not emphasise the human tragedy of it all, I am unsure what does. This great battle was actually a shared experience between the airborne troops and Dutch civilian populations, who obviously could not be evacuated beforehand. Out of this shared suffering, however, arose many tales of courage, kindness – and the Dutch remain immensely grateful that the British and Polish airborne at least tried to liberate them, still revering and mourning the casualties. Indeed, this shared experience has led to innumerable lasting friendships between Arnhem veterans and the families of casualties with their Dutch hosts at the annual pilgrimage, and nobody could forget seeing Dutch children annually laying flowers on the airborne graves.

Some years ago I went to Arnhem and felt an immediate connection with the place and Dutch people, and was profoundly moved by the whole story – especially the Airborne Cemetery. I resolved to research the lives of some of these casualties and publish their stories – bringing into sharp focus the ‘hidden history’ of the dead who have no voice. After years of research, Arnhem 1944: The Human Tragedy of the Bridge Too Far was published by Pen & Sword in 2019 – providing an original approach to an oft-trodden subject. The book includes the story of thirty British, Polish, Canadian and Dutch casualties, a chapter on the complex issues surrounding German casualties, and much else besides – not least many unpublished photographs from family archives. That this research and concept was so personal, moving, and original resonated with many people, empowering me to make a significant contribution to the 75th anniversary of this great airborne battle in September 2019.

On 18 September 2019, I had the honour of delivering an illustrated presentation on the project at the Airborne Museum Hartenstein – formerly General Urquhart’s Divisional HQ. In the audience were ‘Arnhem Royalty’, including the lovely Sophie Lambrechtsen-ter Horst, daughter of Kate, the so-called ‘Angel of Arnhem’ whose home became a field hospital, and historian Dr Robert Voskuil. Importantly, many families of the fallen included in the book were present, having travelled from England, and many Dutch survivors and friends who had so kindly helped me along this unique journey. It was a terrific evening, concluding with an overwhelming standing ovation led by Sophie and Robert. Incredible! My German friend Uwe Pinnau managed to record some video, which can be watched here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ldE-xvgZntE&feature=youtu.be

Having spent several days showing certain families of casualties around the Arnhem and Oosterbeek area, all of whom had become great friends, on Friday 20 September 2019, my exhibition The Human Tragedy of the Bridge Too Far opened at the Airborne At The Bridge annex of the Airborne Museum. The exhibition featured the stories of some of the men featured in the book, families having loaned medals, documents, photographs and other personal artefacts. With a panoramic view of Arnhem Bridge, it was a perfect setting to share these stories. I was honoured that Fred de Graaf, a former President of the Netherlands Senate and currently Chairman of the Airborne Museum, opened the exhibition together with Sophie and Robert. With so many families of the fallen assembled, it was another moving morning – which concluded with the taking of a photograph showing family representatives holding portraits of their ancestors with Arnhem Bridge behind. To see how proud and moved all of these people were made the whole project worthwhile. The photograph was widely shared by the national and regional media in the UK, which you can view here.

The following day, a short service to commemorate the 10th Parachute Battalion took place in Oosterbeek, outside the house on the Utrechtseweg in which the Battalion fought to virtual annihilation. Significantly, Lieutenant-Colonel Andy Wareing, commander of today’s 4 PARA, and who had that morning participated in the mass parachute drop on Ginkel Heath, laid a wreath at my request in memory of Private Albert Willingham – who famously gave his life by jumping on a grenade to save wounded comrades and Dutch civilians. The Willingham family were present, and it was quite something to show them the house where this happened, 2 Annastraat, and gain access to the actual cellar where all of this happened. Albert’s story is told in full in the book, and was widely reported upon by the media as a result of our efforts to raise awareness of his courageous story. You can view it here.

The week’s conclusion, as always, was the packed annual memorial service at the Airborne Cemetery, which words are inadequate to describe. What happened there is actually something for another blog, but this provides a taster.

So, the book has already been updated and re-printed, the exhibition closed but having contributed to the spike in visitor attendance, which reached 100,000.

What a journey… but… today, owing to financial constraints caused by the CV-19 pandemic, the recently restored and upgraded Airborne Museum Hartenstein is already threatened with financial run and closure. Please watch this video of my friend Sarah Heijse, the Director, explaining this desperate scenario and appealing for help – and please share on social media – and donate!

https://youtu.be/ryn5xZdUCI4

Dilip Sarkar MBE FRHistS

Order Arnhem 1944: The Human Tragedy of the Bridge Too Far here.

Dilip Sarkar’s website

Airborne Museum Hartenstein

Watch a This Is Your Life episode featuring Lt Col Frost here: –

Commonwealth War Graves Commission: https://www.cwgc.org