Manning the Munitions Factories in the First World War

Doing Their Bit

Author guest post from Andrew Rawson.

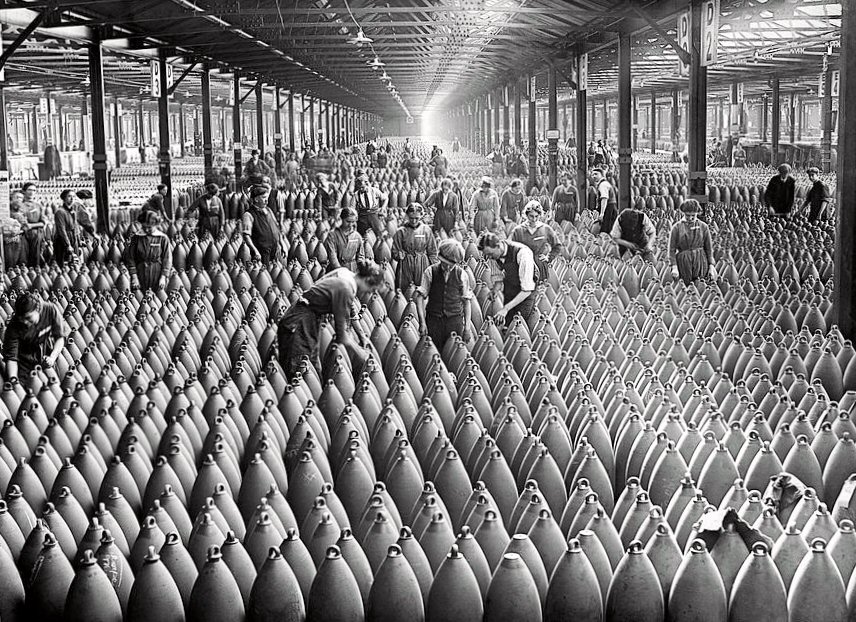

At the start of the Second World War, the British government wanted to know how many people it would need for the armed forces and the armaments industry. So, it looked back at the figures worked out by the Ministry of Munitions in 1918 as a guide. It discovered that for every one hundred servicemen in the Royal Navy, the Royal Air Force and the British Army, there were seventy-eight men and women working in the munitions factories.

The government also made sure it did not make the mistake made in 1914, when Field Marshal Earl Herbert Kitchener told men that the country needed them to join the Army. It had been a mistake because many men who had the skills required by the munitions industry, left their work and enlisted in Kitchener’s New Armies. It meant they had to train without uniforms, weapons and ammunition for many months, when they could have been making them. Instead, the government in 1939 stopped those with key jobs in the armaments industry from enlisting or being conscripted.

The government’s call to stop making luxury goods, to save raw materials, such as coal, iron ore and steel, also caused problems. Factories shut down and their employees signed up, as much to pay their bills as serve their country. That was because unemployment insurance was limited to a few jobs and for short periods back in 1914. The decision meant that the demand for coal plummeted and one in four miners, over 200,000, were put out of work. They too joined up, leaving the steel foundries short of coal when the armed forces were calling for more ammunition.

These factors contributed to a shell crisis which occurred in May 1915, when it became known that the Army had insufficient ammunition for their guns. David Lloyd George was put in charge of a new Ministry of Munitions in July and he put heads of business to work, finding solving the problems. They had to find out each factory’s requirements while, new Munitions Work Bureaux interviewed candidates. Meanwhile, Lloyd George also appealed to workers to show the same loyalty to their work as the men in the trenches were.

Companies were encouraged to switch their production from luxury goods to munitions. For example, my journey started when I discovered that Dixon’s of Sheffield had switched from making expensive silverplated tableware to making the steel Brodie helmet. Which is why I call my talk on the city’s wartime industry, ‘Tea Pots to Tin Hats’.

The Ministry employed the ‘King’s Squad’, skilled men who moved around the country, setting up new factories and training the workers. It also tried a ‘Release from the Colours’ scheme, which allowed skilled men to temporarily return to their companies, to help fulfil munitions contracts. The men were told were that factory work was equal to work in the field but many wanted to stay with their comrades. Some unscrupulous volunteers lacked the skills they claimed to have and used the opportunity to try and get out of the Army.

In some areas many more worked in factories than enlisted. For example, in although Sheffield only raised one battalion of New Army men, 75,000 men ended up working in its steel foundries and workshops, making munitions. Some were targeted by the recruiting sergeants, while others were called cowards for not joining up. So, the Ministry introduced War Workers badges for essential workers; to prove they were ‘doing their bit’ for the war effort.

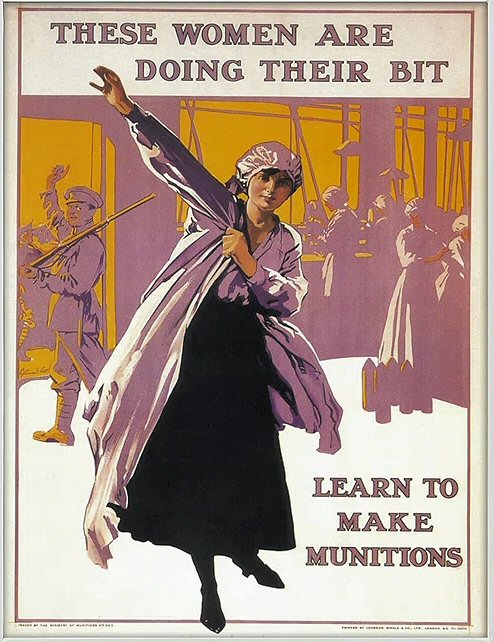

The Ministry soon found itself struggling to find enough men to fulfil all the munitions contracts. The British Army had expanded ten-fold in size and it required ten times as much of everything. So, agreements were made with the trade unions to employ unskilled workers, a process called dilution. Restrictions on work practices were lifted, while complex tasks were broken down into simple ones and organised as production lines. Women were also encouraged to ‘learn to make munitions’ and ‘do their bit’.

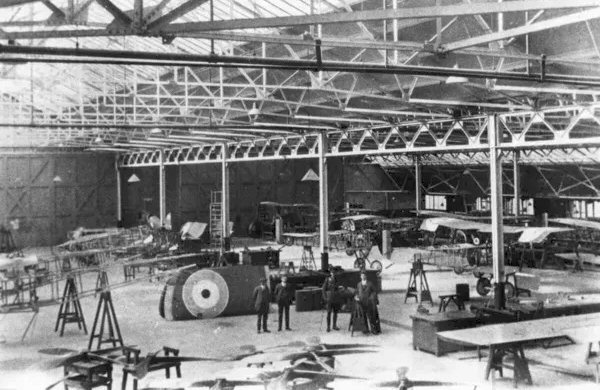

Tens of thousands of women enrolled out of patriotism, or because they wanted to support their loved ones in the trenches; some saw it as an opportunity to earn money. While many were sceptical about how women would cope, they did everything from making shells to building aircraft.

Women were paid the same as men, when doing traditional men’s work because the trade unions did not want them being employed as cheap labour in place of their members. However, they were paid less when doing traditional women’s work or new jobs, of which there were many. The Ministry and trade unions also agreed that the women would be made redundant when the war ended, so the men could go back to their jobs.

Over time, inspectors found out which workers could be combed out and replaced, so they could be enlisted and replaced. Many factories ended employing around 80 per cent women and they were supervised by older charge hands, while experienced mechanics serviced the machinery. For example, the cordite factory at Gretna, in Scotland employed around 17,000 women at its peak. Most had never been away from home, never mind worked in a factory before, so facilities and accommodation had to be improved to encourage them to stay.

The First World War came to an end when the Armistice was declared on 11 November 1918. The Ministry told the factories to immediately stop making munitions and lay off their workers. Women went home; many were widows or were mourning their dead sweetheart. Others had to look after husbands or boyfriends who were maimed or broken by their wartime experiences.

The demobilisation of the armed forces allowed tens of thousands of men to return to their jobs. They discovered that factory life would never be the same again. Before long, many would experience unemployment, as the country’s economy fell into a deep recession.

Order your copy here.