The Miners’ Strike 40 years on – Jane Ainsworth

FROM 1847 TO 1984

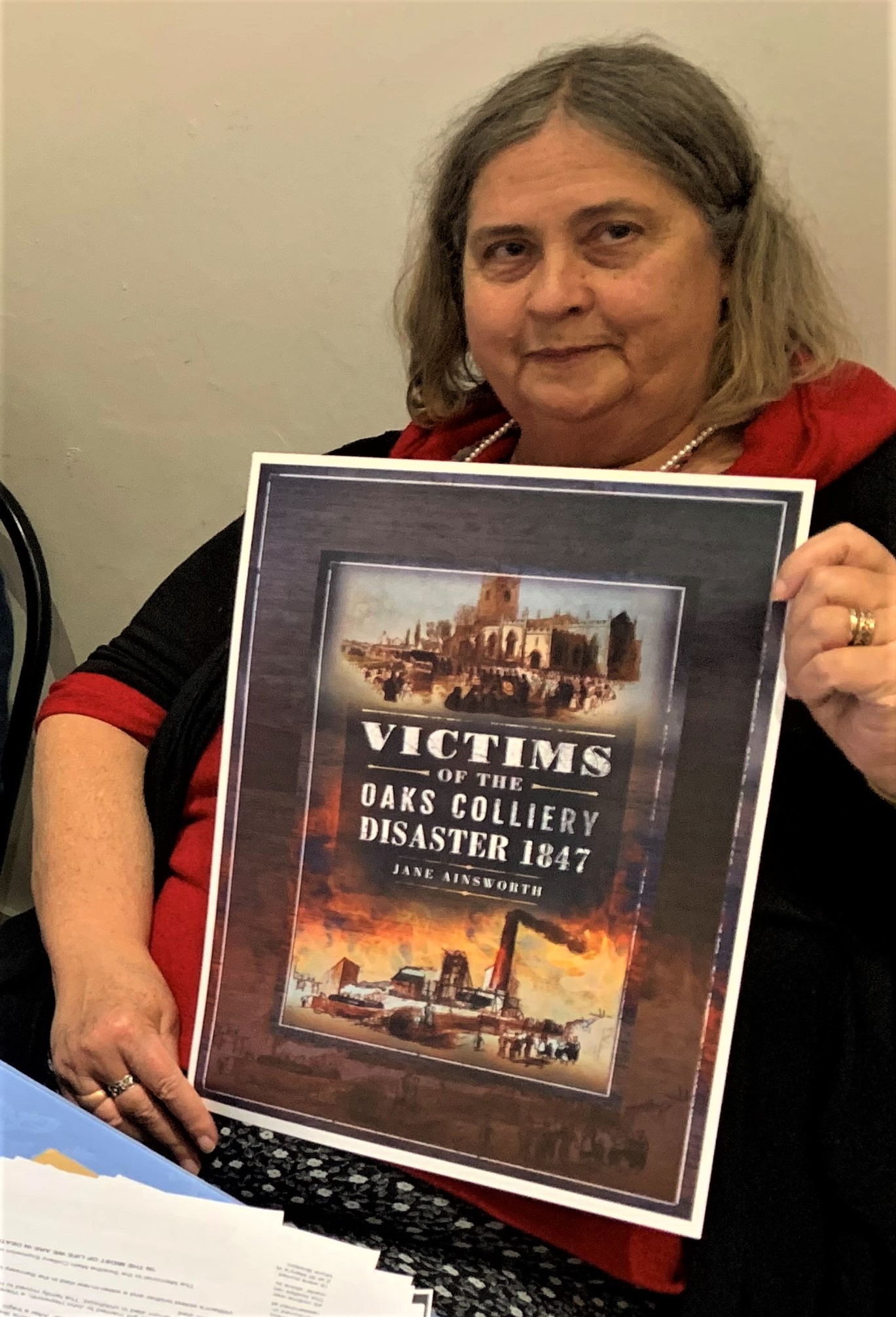

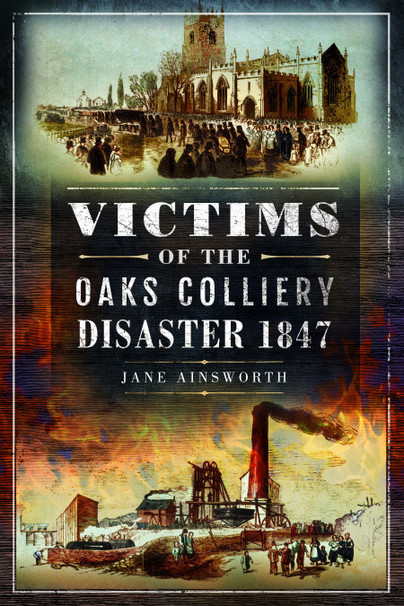

My third book “Victims of the Oaks Colliery Disaster 1847” was published in 2021 by Pen & Sword. I was keen to focus on Barnsley’s mining heritage after my first two books, published by Helion & Co, told the true stories of individuals and their families in WW1 – “Great Sacrifice: the Old Boys of Barnsley Holgate Grammar School in the First World War” and “Keeping Their Beacons Alight: the Potter Family of Barnsley and their Service to our Country”.

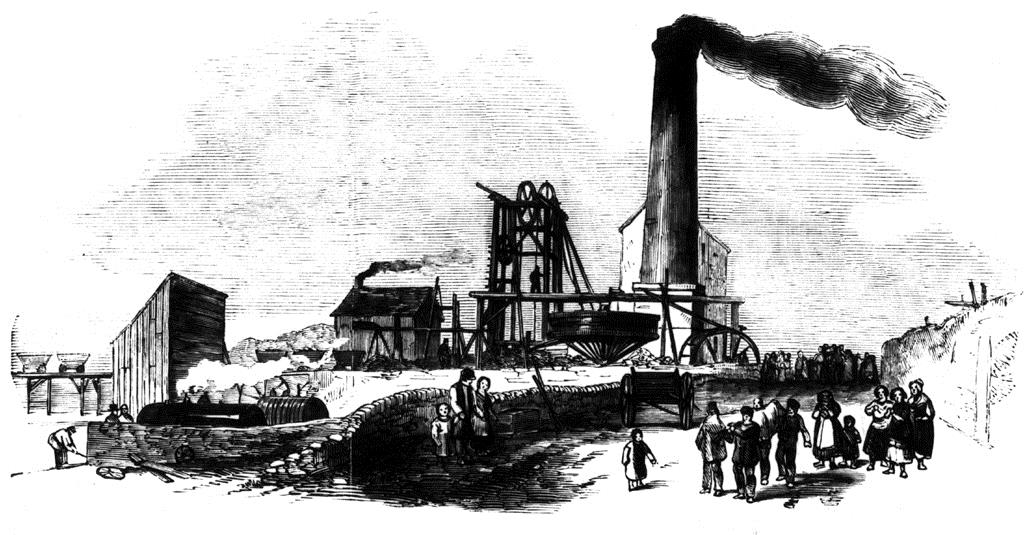

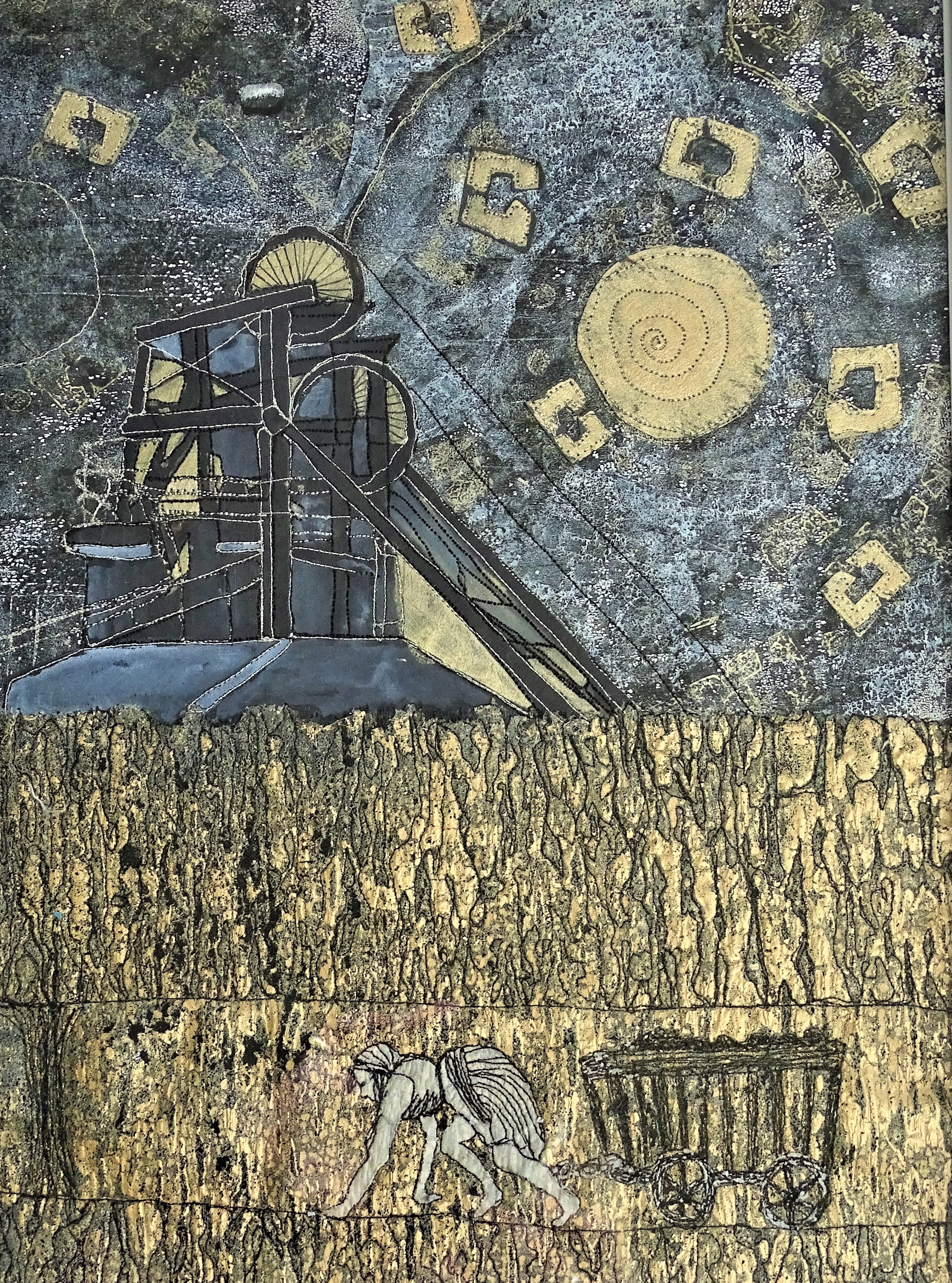

The world was very different 137 years before the Miners’ Strike of 1984 and it has changed even more in the 40 years since, with the fast development of IT and environmental concerns about fossil fuels. Coal has become a dirty word but for 150 years miners could feel proud that their labour provided the power for the country’s homes, factories and transport while contributing towards victories in two world wars.

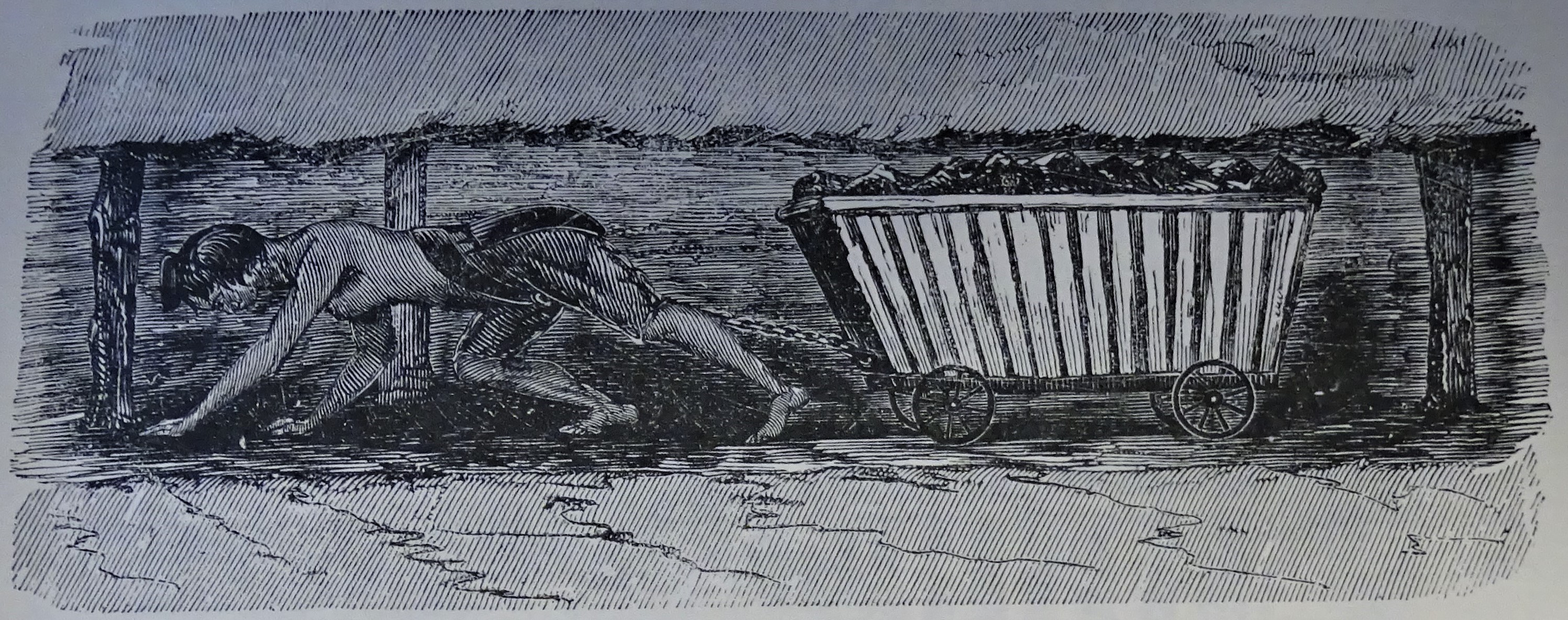

In 1847, people died of diseases that can be treated today, there was no free medical care, no NHS, no welfare benefits system or retirement pension, access to clean drinking water as well as safe disposal of sewage were unreliable, housing standards for poorer people were generally appalling and education was limited. The Industrial Revolution led to many workers relocating from rural areas to towns and cities in search of employment, but most lived in poverty. Families owned few possessions, often lived in one room, sharing beds ‘top to toe’ even with strangers, and they subsisted on meagre, unhealthy diets. While some reports into sanitation and working conditions began to improve things from the early 1800s, with the Royal Commission in 1842 prompted by the Huskar Pit disaster, they were largely ineffective until after 1847.

Two significant common threads are that mining communities rallied round to help each other at times of adversity and that grave injustice was caused to workers by those in authority.

Like a lot of local people, many of my paternal ancestors were mineworkers. My Hardy bloodline clocked up over 100 years labouring underground between them, but they did not work at the Oaks Colliery and they were not involved in the Miners’ Strike of 1984. A few extended family members were killed in accidents but none in any disasters.

My great, great grandfather John Hardy (1831 – 1891) left the uncertainties of agricultural work in Woolley for employment in the pit by 1861. He moved to Darton, where both sons toiled alongside him. My great grandfather Charles Ernest Hardy (1863 – 1932) relocated to Worsbrough then Elsecar, where our family remained. His sons, including my grandfather Joseph Hardy (1887 – 1963), were fortunate to be employed by Earl Fitzwilliam. His elder surviving son, my uncle Thomas Hardy (1910 – 1996) took a mining technology diploma and became a deputy; my father, as the youngest of seven children, escaped that destiny and qualified as a secondary schoolteacher.

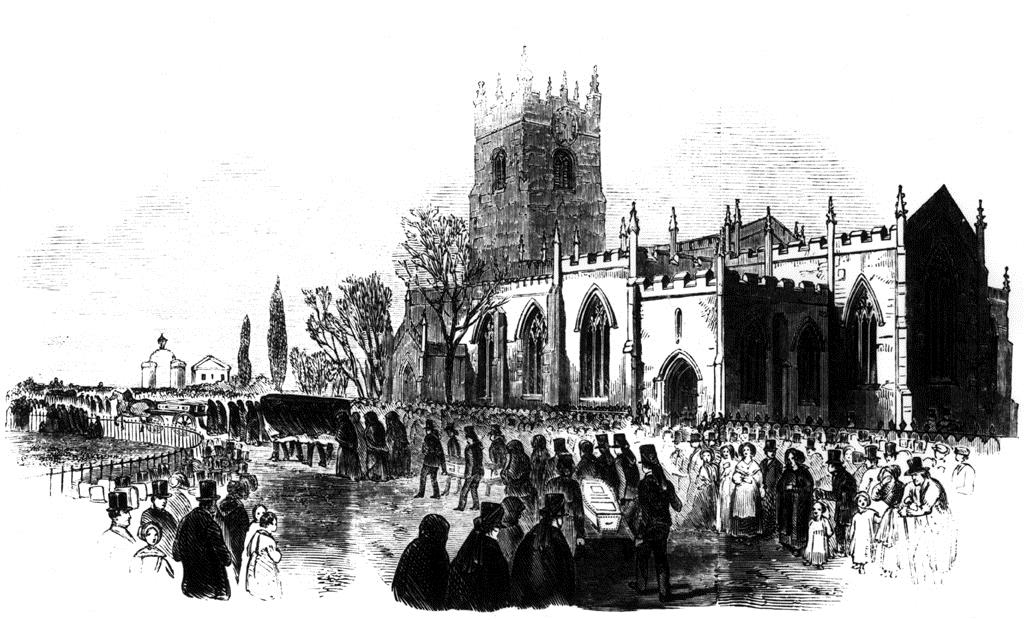

I was inspired to write “Oaks 1847” by the 150th anniversary project to identify the 361 victims of the 1866 Oaks Colliery disaster – widely remembered because it was for a long time the worst anywhere – and a ledger that Barnsley Archives had recently acquired containing minutes of the 1847 Miners Relief Fund. Aware of the notoriety of the Oaks Colliery for explosions with loss of life, I wanted to research a disaster that had been largely forgotten. I welcomed the challenge of revealing the stories of the 73 men and boys killed, plus a few who survived with injuries, at a time for which few records are available. I felt it important for the victims and their families, whose lives were also affected, to be remembered as part of Barnsley’s history. Regrettably, there is no memorial to these victims and it is far too late now for them to receive justice.

Mineworkers did not have a trade union until the South Yorkshire Miners Association was founded in 1858 and it fought for mineworkers and their families to receive compensation from colliery owners following an injury or death at work. Before this any allowances or funeral costs depended on whether workers could afford to join one of the many ‘Secret’ (Friendly) Societies in existence at the time or they relied on the generosity of donors to disaster relief funds to support widows and orphans.

The 1847 fund was managed by the usual Barnsley worthies, all male and judgemental, comprising solicitors, clergy and colliery owners or managers. Even when there was culpability from the owners, Coroners’ Inquests recorded verdicts of “accidental death”; just like the men killed on WW1 battlefields, miners were deemed of little value, replaceable and “cannon fodder”.

I watched the recent TV documentaries about the 1984 strike with fascination and disgust at the appalling behaviour of the Police towards miners, as encouraged by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. The miners, on strike or at work, were “organised” with union support in place – I leave to those much more knowledgeable than me to judge the motivation and effectiveness of Arthur Scargill’s actions. I would certainly support a Public Inquiry, which is long overdue, and it would be good to see justice done for those involved within their lifetime.

Order your copy of Victims of the Oaks Colliery Disaster 1847 here.