Women’s History Month – Carol-Ann Johnston

6 things you didn’t know about Jane Seymour

Third wife…. or first?

We all know Henry VIII had six wives and thanks to a popular rhyme we know what happened to them: Divorced, Beheaded, Died, Divorced, Beheaded, Survived.

However, in Henry’s eyes he only ever had two wives: Jane Seymour and Catherine Parr. Catherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn and Anne of Cleves marriages were annulled and whilst Catherine Howards was never formerly annulled, the Privy Council on Henry’s orders announced that she was no longer to be styled as Queen but only referred to as Lady Catherine Howard following her disgrace.

At his funeral in 1547 only the coats of arms and banners of Jane Seymour and Catherine Parr appeared in his funeral procession.

Jane or Joan?

There was no standardised spelling in Tudor times and people even spelt their own names differently on occasion. Jane signed herself as Jane in the few surviving signatures we have of hers but there is surviving documentation that refers to her as Jane, Joan, June, Joanna (Ioanna/Iohanna) and Jeanne (Ieanne) as well. On coins and engravings Janes initial was represented by the letter ‘I’ as there was no ‘J’ in Latin at the time. Her surname has even been spent differently too, it has appeared documented as Seymour, Semel, St Maur, Semer and possibly Seamowre.

Expert Seamstress

Jane was regarded as an expert needlewoman and some of her work survived in the Royal household until 1652 when it was returned to a descendant of her brother Edward. The items consisted of ‘’Five pieces of Chequard hangings of coarse making, having the Duke of Somerset’s Arms in them, And one furniture of a bed of Needlework with a chaise and cushions suitable thereunto’’. A Gilt Bedstead was also returned.

Cravings

Whilst pregnant with her only child the future Edward VI Jane had cravings like a lot of pregnant women, and fortunately for us we know what they were: Quails and Cucumbers. Her stepdaughter Mary personally sent her Cucumbers from her own gardens, but Henry and his council were forced to look abroad to satisfy her longings for Quail. The Lord Deputy of Calais, Arthur Plantagenet 1st Viscount Lisle, shipped hundred’s over after sourcing them from Calais and Flanders.

Jilted Bride

Prior to her marriage to Henry VIII a potential match for Jane was discussed with the Dormer family. William Dormer was the only son and heir of the wool merchant Sir Robert Dormer of West Wycombe and Wing and his wife Jane Newdigate of Harefield Middlesex. It is unclear who first proposed the match or how far the talks went but it fell through, and two reasons have been given for this and both are connected to William’s mother. It has been suggested that she was unhappy with a distant cousin of the Seymour’s Sir Francis Bryan who may have arranged the match. Sir Francis did not have a good reputation, later earning himself the nickname’ the Vicar of Hell’ for his unscrupulous dealings and behaviours the second reason is William’s mother did not think Jane was a good enough match for her son whether through birth, the amount of dowry she would bring, or a scandal connected to her father who reportedly had an affair with one of his sons wives. It’s interesting to speculate what she thought when Jane became Queen of England.

This prior negotiation never caused Jane any problems and left her with her reputation intact, in fact she emerged from it as a sort of Cinderella who was jilted and then went onto marry a more prestigious man.

Relative of three of Henry’s other wives

Jane was the second half cousin of Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard through a shared ancestor Elizabeth Cheney. Elizabeth married twice first to Sir Frederick Tilney with whom she had one daughter, Elizabeth Tilney who married Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey later 2nd Duke of Norfolk. Elizabeth and Thomas would have nine children including Elizabeth and Edmund Howard. Elizabeth went on to become the mother of Anne Boleyn and Edmund the father of Catherine Howard. Elizabeth Cheney’s second husband was Sir John Say and the couple’s eldest daughter was Anne Say who went onto marry Sir Henry Wentworth, they in turn became the parents of Lady Margery Wentworth, Jane’s mother.

After Henry VIII’s death his widow Catherine Parr would marry Sir Thomas Seymour, a brother of Jane Seymour, making Henry’s third and sixth wives’ sister-in-law posthumously in Janes case.

BONUS

Jane Seymour DID NOT have a caesarean

It’s one of the most believed myths about Jane, that she had a difficult labour, and the baby could not be delivered naturally forcing her physicians to step in and perform a caesarean however it is simply not true.

Jane gave birth to her only child at Hampton Court Palace on 12th October 1537, it had been an easy pregnancy but a difficult birth and her death just twelve days later left her son as motherless as his elder sisters. Whilst the commonly accepted cause of Janes death is Puerperal fever there are still some unanswered questions but what we can be sure of is that she did not die following a caesarean. If Jane had undergone the procedure she would have died shortly after Edwards birth, but she lived for another twelve days, long enough to dictate and sign letters announcing her son’s birth, greet guests following his christening and to be aware of plans for her Churching, a thanksgiving ceremony that acknowledged the pains a mother had gone through and gave thanks to God for her continuing health.

Whilst the Tudors were aware of the procedure, a caesarean was only ever performed as a very last resort: if the mother was already dead or dying to save the infant. A caesarean on a healthy, pregnant woman in Tudor times would have been an instant death sentence and it wasn’t until the 19th century that the procedure could be relatively safely carried out.

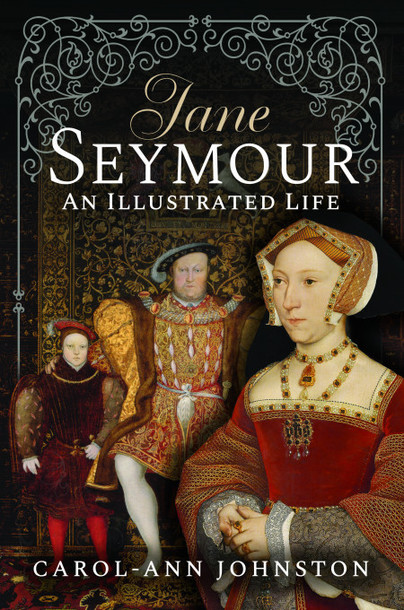

Order your copy of Jane Seymour here.