Women’s History Month – Janey Jones

7 QUESTIONS ANSWERED ABOUT THE EDINBURGH SEVEN

WHO WERE THE EDINBURGH SEVEN?

Seven intelligent, brave, and pioneering Victorian women were brought together by Sophia Jex-Blake with the goal of becoming fully trained doctors at a British university. They arrived in Edinburgh in 1869-71, becoming a cause celebre known as the Edinburgh Seven. The 1858 Medical Act stated that only British degrees were sufficient for inclusion on the British Medical Register. Therefore, women who wished to practise medicine in the British Isles realised they must also study here. That was a problem; no British University offered medical places for women. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson had trained, uniquely, at the Society of Apothecaries, but they turned down all subsequent female applicants. Elizabeth Blackwell had trained in New York. Some British women had gone to Paris and Berne. The only university remotely encouraging was Edinburgh.

The University decided one woman was not viable. So, Sophia advertised for more. They came from all parts of Britain after an advert appeared in The Scotsman newspaper. Edinburgh offered an extra mural style course for the women but resisted the idea of graduation. Around 1872-3, the women realised that despite court rulings in their favour, Edinburgh University had decided they must leave, such damage was the battle between the women and certain Professors doing to the reputation of the University.

2 WHAT BECAME OF THE SEVEN AFTER EDINBURGH?

Most of the women eventually became doctors by completing their training overseas. However, Edinburgh was always dear to their hearts, and they retained an association with the city. Sophia Jex-Blake returned and became Scotland’s first female doctor in 1878, setting up practice in Manor Place in the stylish Westend. Others of the Seven worked as doctors in India, France, and Japan.

3 WHY WRITE ABOUT THEM NOW?

In 2019, I saw a news report that the Seven were being awarded posthumous degrees via current female medical students to right the wrong. As a graduate of Edinburgh, I realised that I owed a debt of gratitude to the women. For their courage in the face of rioting against them, death threats, court cases and vilification. Also, I learned that, according to the Royal College of Surgeons of England, the current ratio of male to female consultant surgeons in the UK is approximately 8:1. On average, women earn 24% less than men in medicine. It’s a timely moment to look at the Edinburgh Seven and say: how far have we really come since the brave fight of these women?

4 WHY DID THEY BECOME A CAUSE CELEBRE?

Sophia had arrived in Edinburgh via travels to the USA. There, she had noted that women’s rights were more progressive. She also observed the power of communication; she published papers about what she saw. In many regards this laid down the foundations of a public relations campaign fought by Sophia. Befriending newspaper editors and politicians, as well as respected doctors who held sympathetic views, giving speeches across the country with the help of new train routes, networking furiously – all of this made Sophia something of a genius in raising awareness of the way Edinburgh University Senatus and Council members were behaving. This skill in Sophia terrified the Old Guard who had no equivalent PR machine. Some members of the established male medical profession began a systematic campaign to oust the high achieving women from the University. At first, there was name calling, hooting, and blocking of doors and seats in lectures. The shared home of the Seven at 15 Buccleuch Place was regularly vandalised.

5 WHAT WAS THE ‘HOPE AFFAIR’?

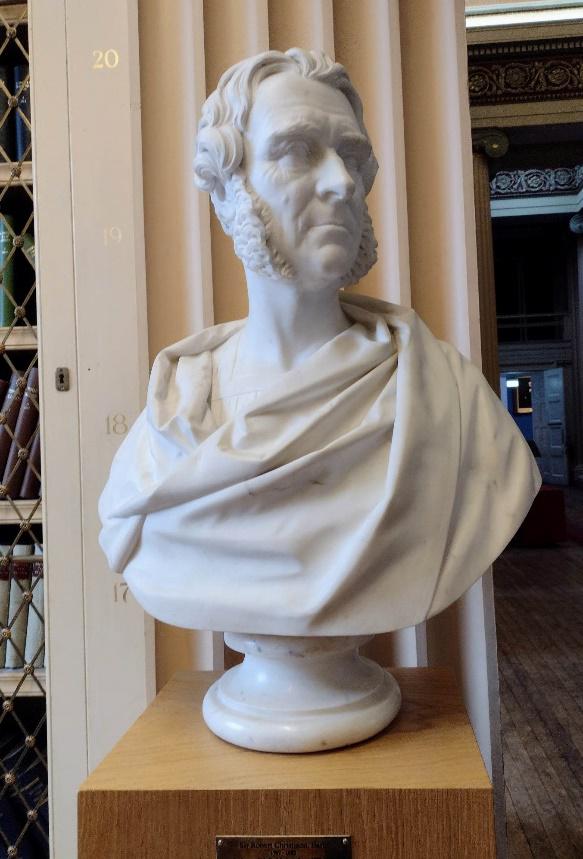

In the spring of 1870, a prestigious prize for the best mark in Chemistry – The Hope Scholarship – had been won by Edith Pechey; one of the Seven. The Professor of Chemistry at the time, Dr Crum Brown, under some pressure from Sophia’s nemesis, Professor Robert Christison, and mindful that male students were resentful of the women’s ability, decided not to give the prize to Edith. This all had an appalling knock on effect for the women because it was decided they wouldn’t get course certificates either, and gradually it dawned that this meant they would not be able to graduate.

6 HOW DID THE CONTROVERSIAL RIOT COME ABOUT?

In the late afternoon of 18th November 1870, the Edinburgh Seven made their way to Surgeons’ Hall, to take an examination in Anatomy. The taking of exams by the women had become very unpopular with certain male students and professors because the women were getting top marks, and were ‘getting ideas’ about full qualification. The women were met by a violent crowd; some from the University’s faculty of medicine, some Sophia called ‘street rowdies’ and other bystanders. The objective was to prevent access to the exam for the women. The Seven linked arms and pressed through the crowd, pelted with mud, rotten vegetables, and abusive words. There was wild singing, drinking, and goading from the rioters. A janitor opened a bolted gate, and some friendly medics ushered the women in. Incredibly, after that disturbance, the women had the presence of mind to take the exam. Newspapers around the world reported the story of the shameful Edinburgh riot.

7 WHAT DID THE COURT CASE ENTAIL?

Sophia was now publicising the women’s cause furiously, and had attended a public meeting for contributors to the Royal Infirmary at the Council Chambers in Edinburgh on January 2nd, 1870, where the topic of the riot had arisen. She repeated some fairly reliable hearsay, about who had started it, and the drunken condition of that young man; Edward Cunningham Craig. He was an assistant to the adversarial Professor Robert Christison. Sophia’s comments incensed Professor Christison and she was soon served with a writ for defamation of character, and was commanded to attend the Court of Session – Scotland’s highest civil court – in June that year. Sophia was supported by the other women who took the stand as witnesses. Certain opponents had suggested the women were unfeminine, witch-like, Magdalenes (reformed prostitutes), uncouth and unnatural.

But the women were described by one man looking on from the back of court as: ‘composed’. They were serene, well turned out, polite and refined. This didn’t fit the narrative at all. In contrast Professor Christison and Edward Cunningham Craig were awkward and nervous. Had Sophia not mentioned intoxication, the case might have been vastly different, but the heavy drinking was impossible to prove, and of the gravest concern to Mr Cunningham Craig, who looked forward to a prestigious career as a doctor. The all-male jury decided against Sophia in terms of the letter of the law, but showed sympathy to her by awarding minimal damages to Mr Cunningham Craig; a way of saying: we support you, Miss Jex=Blake, but our hands are tied.

Hostility worsened after the court case, but Sophia and the other women always behaved with dignity and resolve. By 1876, Sophia had ensured an Act of Parliament to allow women to graduate after studying at British Universities. Thank you, Sophia!

The Edinburgh Seven is available to preorder here.