Women’s History Month – Norena Shopland

They fought for 100 years to keep their jobs

Coal mining is generally regarded as a male profession, and when spoken or written about is often accompanied with pictures that we’re all familiar with, of miners covered in coal dust hewing at the coal face or emptying trams of coal. When women are included, they are relegated to roles such as wives, mine secretaries, cleaners or nurses and their roles in the great coal mining traditions have, for the most part, been wiped out.

There has been work done on the Pit Brow Lasses of Lancashire and several books exist but the dominance of these women has often given a false impression that it was only in that location women worked in coal and few other localities have been covered with the same intensity as Lancashire.

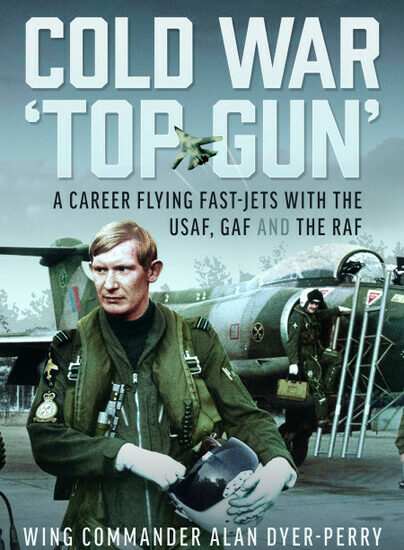

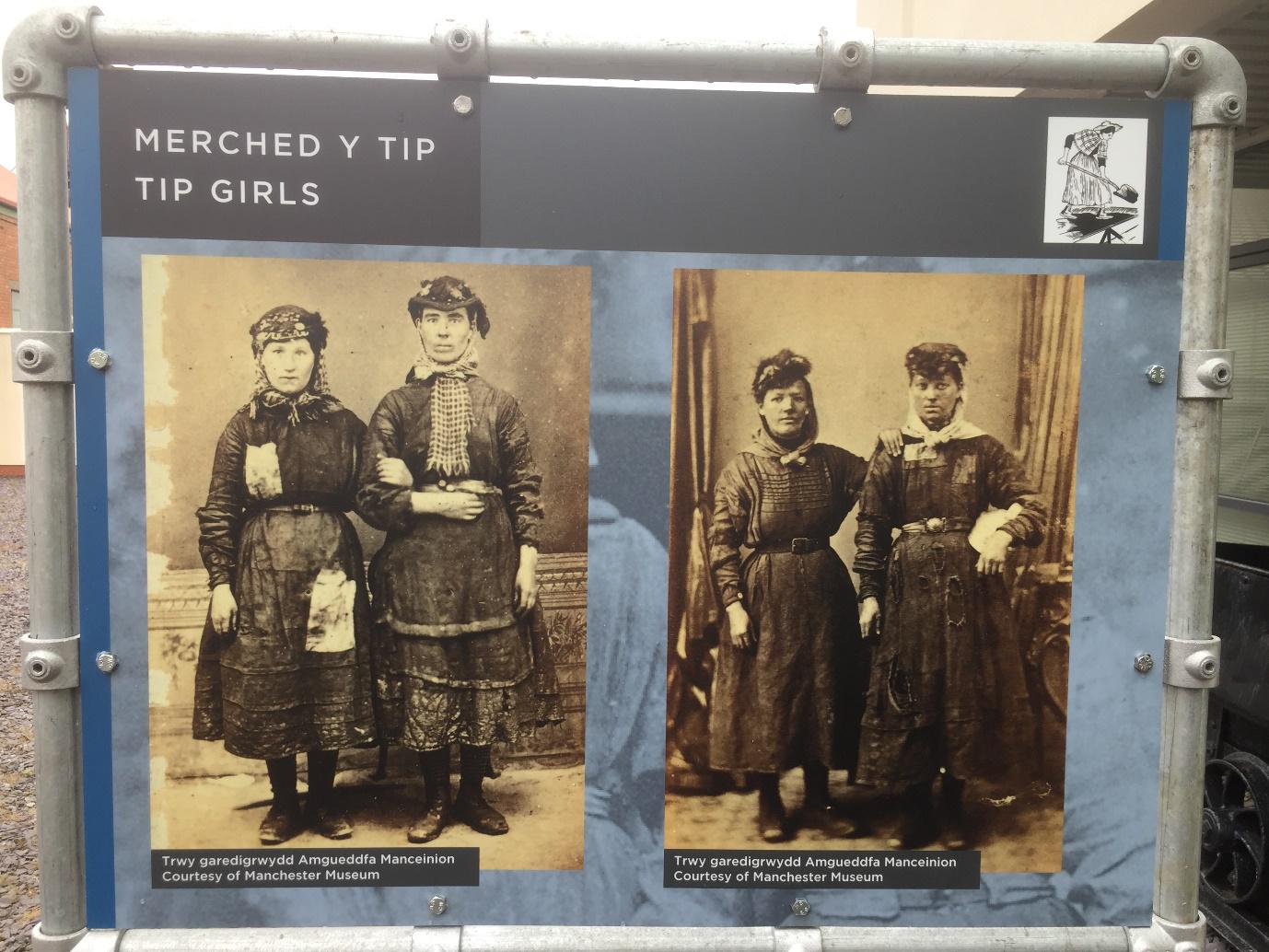

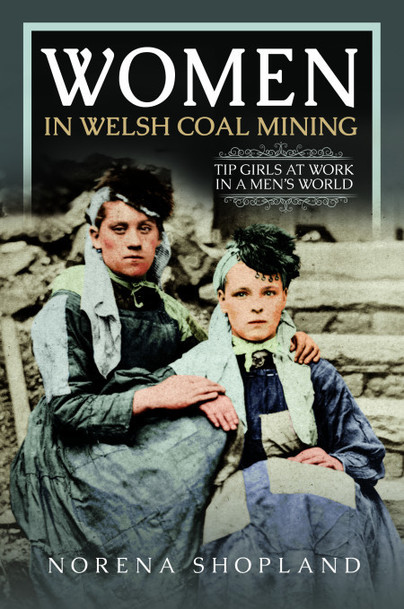

However, while writing A History of Women in Men’s Clothes (Pen and Sword Books, 2021) I became aware of the controversy surrounding women wearing men’s clothes including those in Wales and so I began to look in depth at women working in coal in Wales. Initially a number of people told me I would find little, how wrong they were. Indeed, so much material was uncovered that it resulted in book Women in Welsh Coal Mining: Tip Girls at Work in a Men’s World (forthcoming Pen and Sword Books, June 2023) and an exhibition, curated by Ceri Thompson of the Big Pit Museum, Amgueddfa Cymru in 2021/22 before being relocated to Swansea Waterfront Museum and then on to Rhondda Heritage Park (June 2023). In addition, so much material was left out of the book it leaves possibilities for other works such as dissertations.

So, who were these women?

Prior to the deep coal mining we are familiar with today, extraction was often done in small mines scattered around a coal belt and usually worked by various members of the same family – but fatalities and accidents were high, causing the Government to investigate the way mines were worked particularly the employment of children, often very young children, working long hours in the dark. However, during their investigations, inspectors also became concerned about women working in close proximity to men. The result was the Mines and Collieries Act 1842, the first gender-specific act of parliament, and as of 1 March 1843 all women, no matter what age, were barred from working underground and no boys under ten – but as Inspectors of Mines were not appointed for another eight years it meant the law in many places was simply ignored.

Mainly, because stopping this employment would be to throw many families into dire poverty. Most depended on their children to work, and if parents only had daughters, it meant a massive reduction in wages for those already earning little.

Despite the ban, there were those who evaded the edict by cross-working as men. A practice often enabled by employers who continued to pay them women’s wages for men’s work and who could drop wages even further by threatening to reveal the women if they did not accept the reduction.

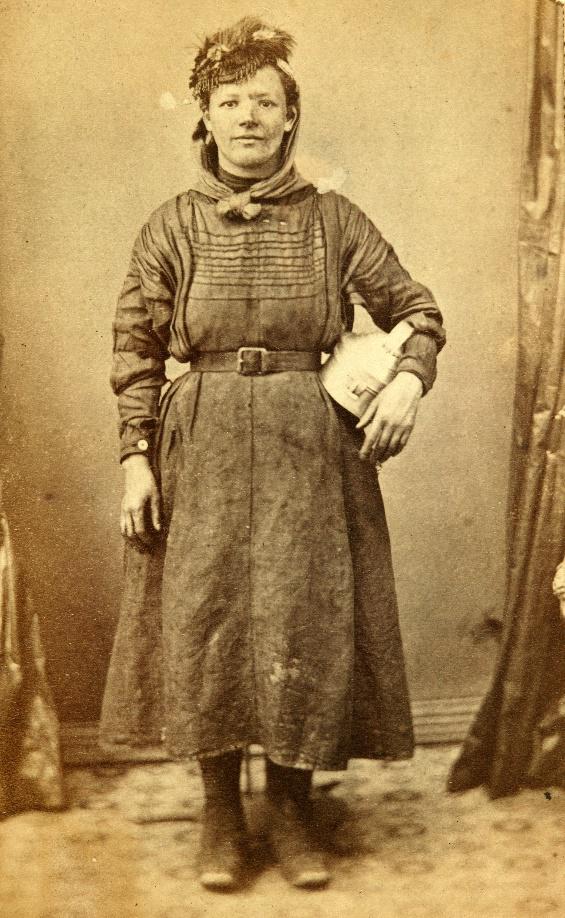

In time though, women were moved onto the pit banks where they would pull the trams arriving full of coal to a sorting shed and shovel out the contents. The coal then had to be cut to a uniform size to fit into the sacks and cleaned as buyers objected to sacks full of coal dust. These were dangerous jobs. Women, and the men who were often old or infirm to work at the coal face, were often run over by trams and seriously injured or killed; and pulling trams from a pit head that descended deep into the ground often toppled women over and they fell to their deaths.

Society took exception to this type of women’s work, the women were covered in dusty clothes with black faces and hands, they swore like the men and, horror, they smoked tobacco. So, society decided to do something about saving these women who did not want to be saved. Go be domestic servants, they were told, but there was little in that line of work for local women. Go work in a factory, said their critics, despite the fact there were few factories. Instead, the women clung to their jobs as society branded them immoral, that they had ‘unsexed’ themselves so no long fit to be called women. Tourists came to ogle at them, postcards could be bought of them, and questions were asked in Parliament about this work that turned women into bad wives, bad mothers, and bad housekeepers. In 1866 a Select Committee on Regulation and Inspection of Mines investigated the matter but found none of the accusations to be true, the women they found, were no more immoral than the rest of society and they were not bad wives and mothers.

Nevertheless, the criticism did not abate and the following year a new act of Parliament sought to ban the women yet again. This time the Lancashire women decided to act and marched on Parliament (while it is not known if any Welsh women went, several Welsh MPs spoke in their defence) and Home Secretary Henry Matthews was so impressed he declared that it was wrong for men to hinder the decisions of grown women who knew what was best for themselves.

The pit women had finally won the right to be left alone. They had saved their jobs, been found innocent once again of immorality, their clothes had been accepted, they had been embraced by the women’s suffrage movement, and the radical dress movement campaigning for women to be allowed to wear trousers – now they hoped to be left in peace to get on with their lives.

Things, however, were not going to be that easy.

During the 1895 Miners’ International Congress, men were still seeking to prevent female labour at the pit brow despite the fact their numbers were diminishing due to the introduction of machinery to screen the coal. Finally, in 1911 another initiative by Parliament to ban all women from employment in mines succeeded.

A ban that lasted only three years.

With WWI the number of women who worked at mines rose as the men went off to war. Most wrote positively about their experiences and would have liked to continue but when the men came back the women were ousted. Although not completely, so in 1954 Parliament raised yet another bill which passed, making it illegal for women to work at mines.

As the years rolled by the exclusion of women was retained, even in 1979 when the United Nations General Assembly adopted the ‘Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women,’ which urged that laws restricting women’s work hours and some categories of jobs should be repealed, the UK did not do so. Women at mines duly moved to supportive roles, caring, catering, and administrative.

Since the late twentieth century, UK laws restricting women’s employment, and their pay, have changed to keep them more in line with men’s work and pay, but gender employment and pay gaps persist. Following the Employment Act 1989 women are now allowed to work underground, but few do so.

Today, women’s overall participation in the global workforce is 47%, but only 14% of the global industrial mining workforce, and few are in the higher paying jobs being left predominantly in administrate fields. There are women miners, particularly in the USA, and occasionally articles appear about them and their work – but many speak of being hampered by discrimination and the attitudes of men who believe such work is unsuitable for women. It seems, not much has changed since 1842.

Women is Welsh Coal Mining is available to order here.