Women’s History Month – Neil Buttery

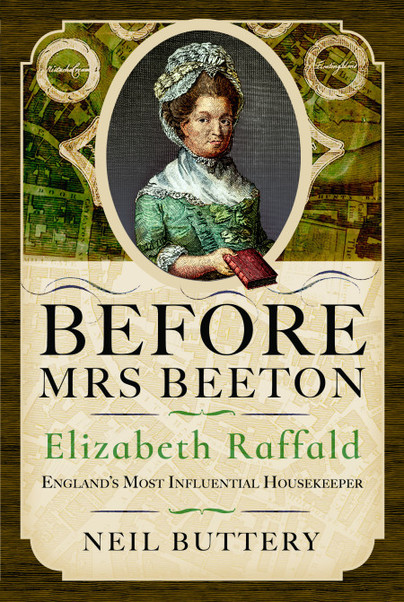

Before Mrs Beeton

Mrs Beeton and her 1861 Book of Household Management is possibly the first name and work we think of when considering great works of cookery writing and recipes that define what we think of today as good old-fashioned British cooking. I certainly did; and well I might, her book is chock-full of good recipes. As it turns out however, the recipes were not written by her, but drawn from a well of recipes written by female cookery writers who had preceded her, and it was they who produced the body of work that would come to define British cookery, not Isabella Beeton.

If you have an interest in cookery and history, you will be familiar with some of her talented antecedents: Eliza Acton, Eliza Smith, and Hannah Glasse. But no one contributed to British cookery quite as much as the great Elizabeth Raffald. Her book The Experienced English Housekeeper, published in 1769, was the cookery book gift for new brides up to a century after her death, making her a household name. Almost every home owned a copy.

Elizabeth helped transform the daily lives of middle and upper-class women and their housekeepers: she wrote in a clear, unpatronizing way (her recipes still work very well), and she booted out the wasteful, expensive and overly-elaborate French cooking, with its overuse of butter, meat and fuel. Her recipes were achievable, economic and good. This is not to say that there wasn’t room for swish parties and fancy cooking, everything is okay in moderation, so when one wanted to pull out all the stops she laid her ‘Directions for a Grand Table’ with accompanying illustrations mapping out for the reader a three-course meal, each course being made up of 25 unique dishes.

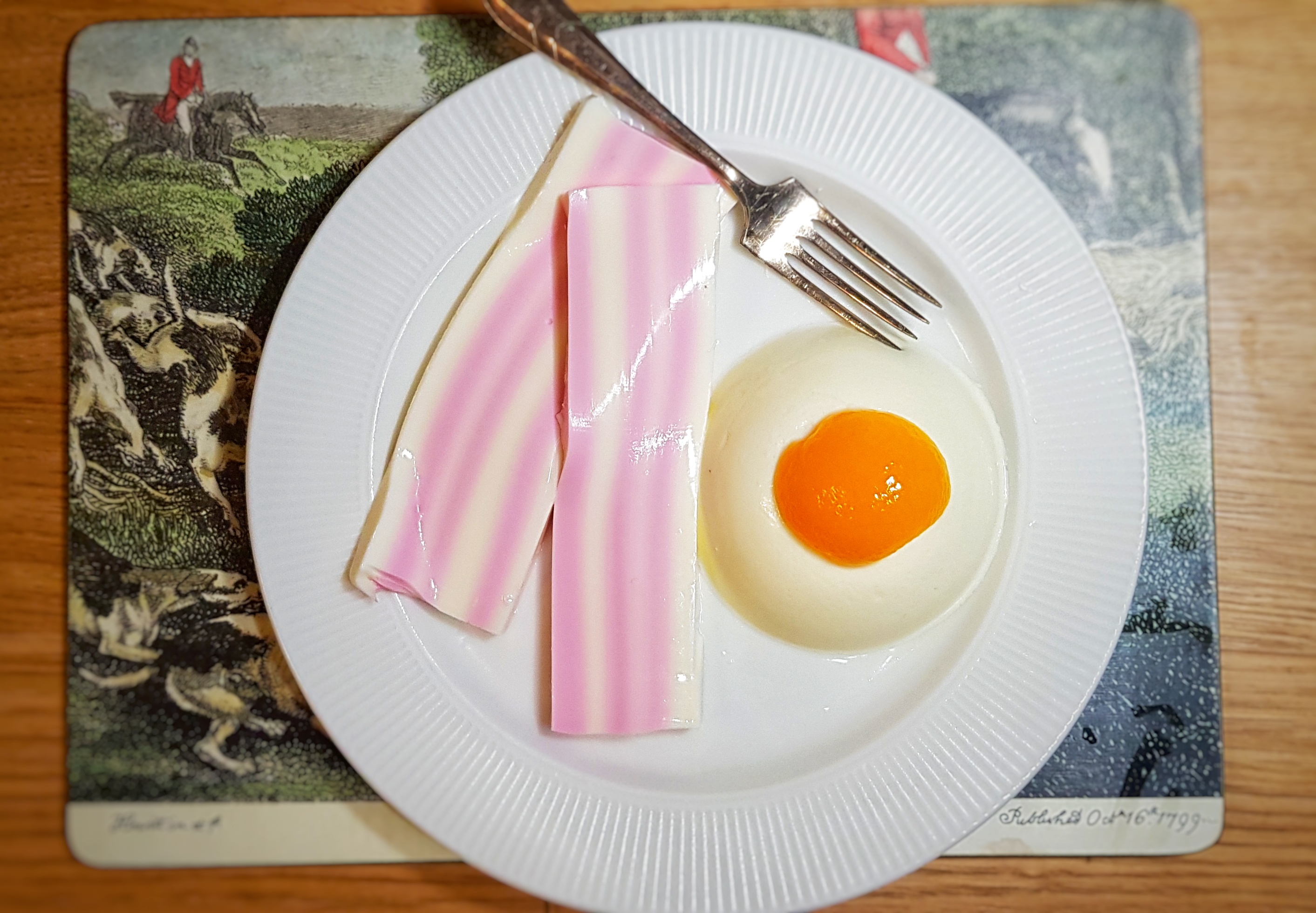

Elizabeth specialised in confectionery and patisserie that also served as table decorations, skills much in demand, and she instructs us on how to make moulded ices and spun sugar nests containing mottoes inside them. Most spectacular were her showstopping jelly and flummery creations; centrepieces made from state-of-the-art thin saltware moulds. Many of these recipes are unique to her, and were widely copied, but never bettered. There is, for example, ‘Solomon’s Temple in Flummery’, ‘Bacon and Eggs in Flummery’, and ‘Fish in a Pond’. Her book contains several other firsts – more everyday ones: she gives us the first recipe for macaroni cheese, for Eccles cakes, and she was the first, it seems, to have the idea of double-coating a fruit cake with both marzipan and icing.

But where did all of this come from? Who was the person behind this amazing, ground-breaking tome? It turns out that Elizabeth’s life and other achievements were as dramatic as they were great.

The Experienced English Housekeeper is a distillation of a half-life in domestic service, and another as a catering entrepreneur in Manchester. She learnt her craft in the big houses of Yorkshire and Lincolnshire, and in 1760, at the age of 25, she became housekeeper at Arley Hall in Cheshire, a young age for a position usually filled by a woman of great maturity and gravity. It was here she developed her showpiece edible table decorations, and where she worked with skilled Head Gardener John Raffald (they would later marry). John grew the exotics of the day: melons and mangoes, paw paws and pineapples which she transformed into cutting-edge desserts and patisserie.

She and John left Cheshire for Manchester in 1763. In the first three years, she opened a shop selling ‘Fine Canterbury and Derbyshire BRAWN’, cured salmon and confectionery, started a catering business that provided food for the dining tables of the better off, and opened Manchester’s first register office – essentially a servants’ temping agency, helping domestic servants find work, and for newly-middle class merchants and factory owners to find good staff; a service most desperately needed. She quickly outgrew her first property, moving to larger premises at Market Place. Here she would sell an expanded selection of foods and exotics of the Empire, start a finishing school for young ladies, write not one, but two editions of Housekeeper, and continue her catering service and register office.

These businesses made her the best-connected person in Manchester, and with these connections, in 1772, she compiled her first Directory of Manchester and Salford; an 18th-century Yellow Pages. Bearing in mind the two towns were made up of around 20,000 inhabitants, this was no small undertaking. She was now a pillar of the community, but later in that year, she and John sold or handed over their businesses and auctioned off the contents of the shop to put all of their eggs in one basket to run the King’s Head, a large tavern, hotel and stableyard. Here she managed to write more editions of Housekeeper as well as another edition of her directory. She also sold the copyright of her book at the third edition – the first woman to do so – making her a rich woman. But with the pressures of juggling so many things, everything started to unravel: John became an alcoholic, there were major thefts, and their cash flow disappeared. How they fell: just a few years after selling the copyright, Elizabeth was bankrupt and forced to take a rundown coffeehouse in the dodgy end of Manchester’s Shambles district. Two years later, at the age of 47, she died of a stroke or aneurysm, her husband so poor that he couldn’t afford her a headstone.

But her book lived on and was a bestseller across the country and was even printed in North America. Her recipes were being cooked up all over the country unifying our food and giving us what we think of today as our national cuisine. Of course, other female writers contributed to this, but none produced work of such clarity and vision. However, recipes by Elizabeth, and other cookery writers too, were needed no longer once Beeton’s behemoth was published in 1861, and Elizabeth faded from memory.

But the influence she has had upon British cuisine (and therefore British identity) needs to be better known and understood; for without her, traditional British food would not exist, at least not in the way we know and love it today.

Order your copy of Before Mrs Beeton here.