81st Anniversary of Operation Dynamo

Desmond Marriott Finny was born on September 12, 1906 at Hill House, Finchingfield, Essex, England. He was quickly attracted to the army, despite coming from a family that was known in the medical field. Desmond was very impressed by his uncle, an Irish veteran of the Great War, who was seriously wounded in Passchendaele. Leading a company of Dublin Fusiliers, he had had the top of his head blown off during an assault but survived into his nineties!

A graduate of the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, Desmond began his career in China with the Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Regiment (Shanghai Defence Force) and then in Mhow (now the Ambedkar Nagar district) in India in 1928. On February 3, 1930, tired of the infantry, he was transferred to the Royal Army Service Corps five days after being promoted to lieutenant. He married Elsie the following year, an English woman he met in India, who gave him a son, John, in 1933. The latter would say of his father: “He was a remarkable man, an exceptionally gallant and slightly eccentric officer with a multi-faceted intellect; indeed, he was rather typically Anglo-Irish.”

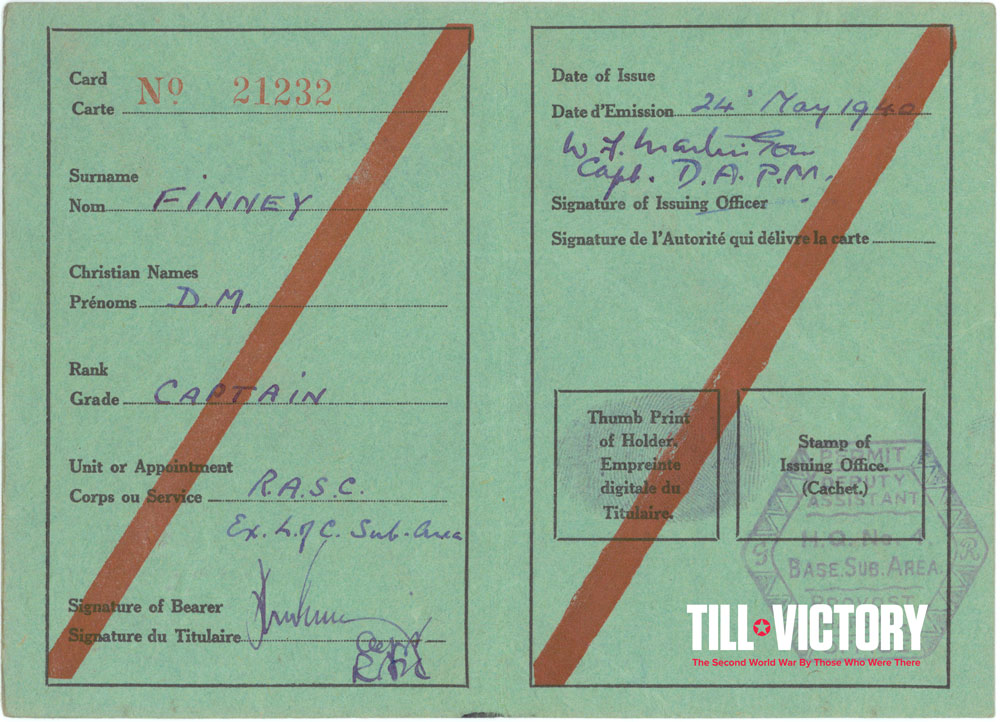

Desmond served in Egypt in 1936. He was made captain there, then mentioned in dispatches for his actions during the great Arab revolt in Palestine. On April 8, 1938, he started working under the Chief Inspector of Armaments in Manchester, a position he held until the declaration of war. Desmond then joined the BEF (British Expeditionary Force) and landed in France on September 19, 1939, assigned to the railway communication lines of the Royal Army Service Corps (RASC). As the ‘Phoney War’ dragged on, he took the opportunity to attend a special training course at Staff College in Camberley, England. In May 1940 he then took on a new position at the BEF headquarters in Arras, just in time to see the Nazi armies set foot on French soil. Attached to the staff of General John Gort (Commander-in-Chief of the BEF), he carried orders from HQ to the various units scattered on the front, using his motorcycle.

Following the failure of the Dyle Plan, as the BEF withdraws in a hurry to the French coast, Desmond continues his round trips from HQ to the front under German bombardment until May 22. His role is starting to become crucial, when he is ordered to lead the way to Dunkirk for the units lagging behind. Among those lost behind enemy lines, he runs into his uncle, Major-General Charles Finny, former head of the Royal Army Medical Corps (retired but recalled to the head of a field hospital) whom he recognizes at a distance in a deserted village by his monocle. “Desmond, what the hell are you doing here?” says Charles. “Uncle, that is the question I have for you” replies Desmond, returning him to safety.

Around 400,000 British, French, Belgian, Polish and Dutch soldiers await a hypothetical ship in Dunkirk. Most of them would embark from the east mole, an area where Desmond will be particularly active. Unfortunately, time is running out: despite the determination and sacrifice of British and French rearguard troops protecting the beaches, German troops are closing in and Churchill estimates that he can save some 45,000 men at best. Miraculously, on May 24, Hitler orders his tanks be stopped on the outskirts of the city, once the beach is within artillery range. The Panzers have been in constant combat for weeks and need to be preserved for the rest of the invasion. Moreover, seven German divisions remained blocked for five days in front of Lille: the courageous and desperate resistance of a corps of the French 1re Armée (half of them being North African troops) slowed down the German advance. This unexpected respite allows the Allies to evacuate large numbers of soldiers and organize their defense. The operation, code named Dynamo, is launched on May 27, 1940.

The Führer’s order is finally lifted two days later, and so begins the battle for Dunkirk, on a front around 5 miles long and 12 miles wide. The Luftwaffe would drop more than 4,000 bombs on the city over the course of a thousand daily missions. Desmond is present on the pier during the German air attack of May 29, when several British ships are lost, including two destroyers. On many occasions, he helps the men get on a boat. Upon their return to England, many would visit Elsie and little John’s home to express their gratitude: “What I myself do remember, even as a small boy, was the constant stream of odd, dirty strangers coming by our Camberley house to give us messages from my father, of being patted on the head by a huge Guards Sgt. Major saying ‘your father, lad, is a wonderful man; he saved all our lives, we’ll never forget’ – and I bet they never did.”

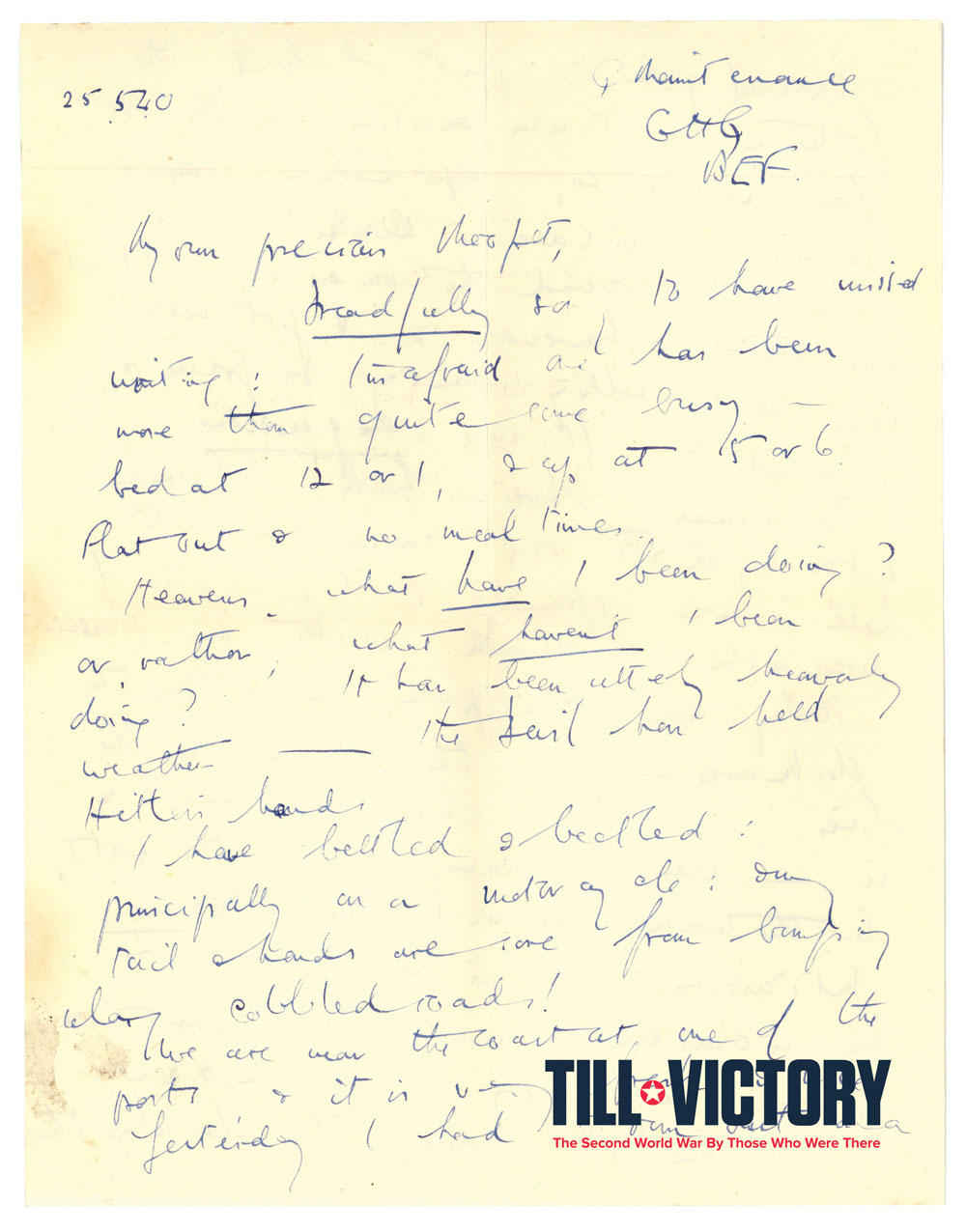

In a letter from Dunkirk on May 25, Desmond describes to his wife the atmosphere in the pocket: “My own precious sweetheart, dreadfully sorry to have missed writing; I’m afraid one has been more than quite busy – bed at 12 or 1, and up at 5 or 6. Flat out, and no meal times. Heavens, what have I been doing? Or rather, what haven’t I been doing? It has been utterly heavenly weather – the Devil has held Hitler’s hands. I have beetled and beetled, principally on a motorcycle. My tail and hands are sore from bumping along cobbled roads! We are near the coast at one of the ports and it is very fresh and nice. Yesterday I had to run out on a special job, just behind the fighting. It was exciting, in the last four miles or so, approaching corners carefully in case a Boche tank should be around the corner! None was there however, and I got into some lovely rolling country, so green and wooded. It was exquisite. The usual hoo-hah, ‘German motorcyclists are coming over the hill’ was sprung, which I was able to quash with my glasses.

Today was principally spent in the dock area – in the smoke of the fires. Bombing has been – is – very heavy in all the ports, but the work goes on just the same. Anti-aircraft fire is terrific. The sky is darkened with shell bursts, and the Boche keeps very high and zigzags. I saw one shot down this evening that came in cautiously low. A great sight! Every so often Spitfires or Hurricanes turn up, so terrific air battles eventuate. One can see them with glasses, specks in the sky, wheeling and turning, with the roar of machine guns and the periodic fall of a plane, the pilot sometimes jumping for it in a parachute. The films are very accurate! I saw a Spitfire shot down through my glasses – exactly as per films! The pilot jumped, and I think he was all right. A German was floating down similarly, about two miles away. They took ten minutes to float down from the great height they were up. I’ve heard bombs whistle too. Most gratifying, because from any reasonable height you can hear the whistle for two or three seconds before the crumps, which gives plenty of time to lie down. I still haven’t had one near me (touch wood). Oh sweet my sweet, I love you so terribly much. I am not brave or adventurous at all these days. I only plot to get back rapidly to my dear, dear Elsie. God bless you, sweet, sweet love, and tell Poosle I love him. I am half asleep and must go to bed. What adventures I will have to tell when I come back! I am feeling awfully fit and am doing myself very well. Ever your own, Des.”

During the first few days, evacuation is very slow and the men waiting on the beaches make easy targets for enemy aircraft. The role of the Royal Navy in the operation is vital, but not sufficient, and the French and Merchant navies must provide full support to Operation Dynamo. Following the Admiralty’s call on the BBC, many British, French, Belgian and Dutch fishermen and yachtsmen, who also volunteered for the evacuation of Calais and Boulogne-sur-Mer, start putting their boats to work. In addition to the 200 warships, 700 private boats (coasters, barges, yachts, tugboats, ferries, trawlers…) are requisitioned to hastily recover BEF and Allied soldiers. On the beach, General Harold Alexander himself, commander of I Corps, asks Desmond to leave the pocket as he has done more than his share. Desmond’s last action in France is to push out a raft with a mixed Anglo-French band of non-swimmers to a waiting boat. He finally leaves Dunkirk on the night of June 2-3 with some of the last soldiers and the staff of John Clouston, the Canadian commander of the Royal Navy (in charge of the east mole, killed during the day). All in all, 338,226 soldiers have been evacuated, including more than 120,000 French soldiers (many of whom will be sent back to France) but also Belgians, Dutch, Poles and Norwegians, during what Churchill will later call “the miracle of Dunkirk”.

At the end of the operation, in his speech to the House of Commons on June 4, Churchill reminds everyone that wars are not won with evacuations, while at the same time galvanizing the British and calling on the Americans: “Even though large tracts of Europe and many old and famous States have fallen or may fall into the grip of the Gestapo and all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule, we shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender, and if, which I do not for a moment believe, this island or a large part of it were subjugated and starving, then our Empire beyond the seas, armed and guarded by the British Fleet, would carry on the struggle, until, in God’s good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the old.”

When Dunkirk falls into German hands, 40,000 French and British defenders are taken prisoner, after receiving the order to stop their heroic fight to protect the boarding operations. According to Desmond, “they saved the show”. Despite the many evacuees, in addition to the men captured on June 4, nearly 200 boats sank, including 6 British destroyers and 3 French; 177 aircraft were lost defending the pocket, while inflicting 240 losses on the Luftwaffe, and 11,000 men died in the bombings or during the street fighting.

Upon his return to England, Desmond is reunited with his wife and son, accompanied by a few officers in pitiful condition but determined to celebrate their survival. He would soon join the Headquarters Staff, X Corps, Northern Command, in Yorkshire. For his bravery during the evacuation, he is awarded the Military Cross, one of the highest military honors in the United Kingdom, and promoted to major. Unfortunately, his promising career is abruptly interrupted on the evening of July 30, 1940. Summoned to HQ at a late hour, because of the blackout which prohibits the use of vehicle headlights, his motorcycle collides with a truck: Desmond is killed instantly at the age of 33. He was to receive his medal a week later from King George VI at Buckingham Palace. His widow Elsie will take his place at a special ceremony in the King’s personal air raid shelter on 17 September. Holding back her tears with courage, she would only announce his death to little John once the family had settled with her grandparents in January 1941. Elsie will never remarry… According to her, Desmond had been enough for a lifetime.

From the mountains of Italy to the beaches of Normandy, and from the deserts of North Africa to the ruined German cities, follow the journeys of more than fifty Allied soldiers (American, British, French, Canadian…) as they liberate Western Europe from Nazi rule, sometimes at the cost of their own lives. Arranged in chronological order and placed in historical context, their incredible stories and unpublished correspondences are illustrated with many personal photographs, war memorabilia and original uniforms.. French author Clement Horvath has spent more than 15 years collecting wartime letters and researching the stories of hundreds of World War II soldiers, and finding their descendants all over the world to honor these heroes in Till Victory. All these years of hard work and passion have made his book an award-winning bestseller in France. The English version “Till Victory – The Second World War By Those Who Were There” is now available at Pen & Sword Books!