Author Guest Post: Daniel MacCannell

Those of us who ponder what would have happened if Napoleon Bonaparte had launched a full-scale invasion of Britain often focus on the land campaign: the withdrawal of the Woolwich Arsenal via canal to Weedon Bec, and the great test – in the fields and woods of Kent – of whether the ‘American’ guerrilla tactics taught by Gen. Sir John Moore and championed by the Duke of York could win out against the might of France. Trafalgar, meanwhile, is seen as a sort of ‘on/off’ switch. Win it, and the French cannot invade; lose it, and they must. But, as well as being simply untrue, this is to ignore the most interesting aspect of coastal-defence and invasion doctrine of the era: reliance on huge swarms of small, highly specialised inshore watercraft.

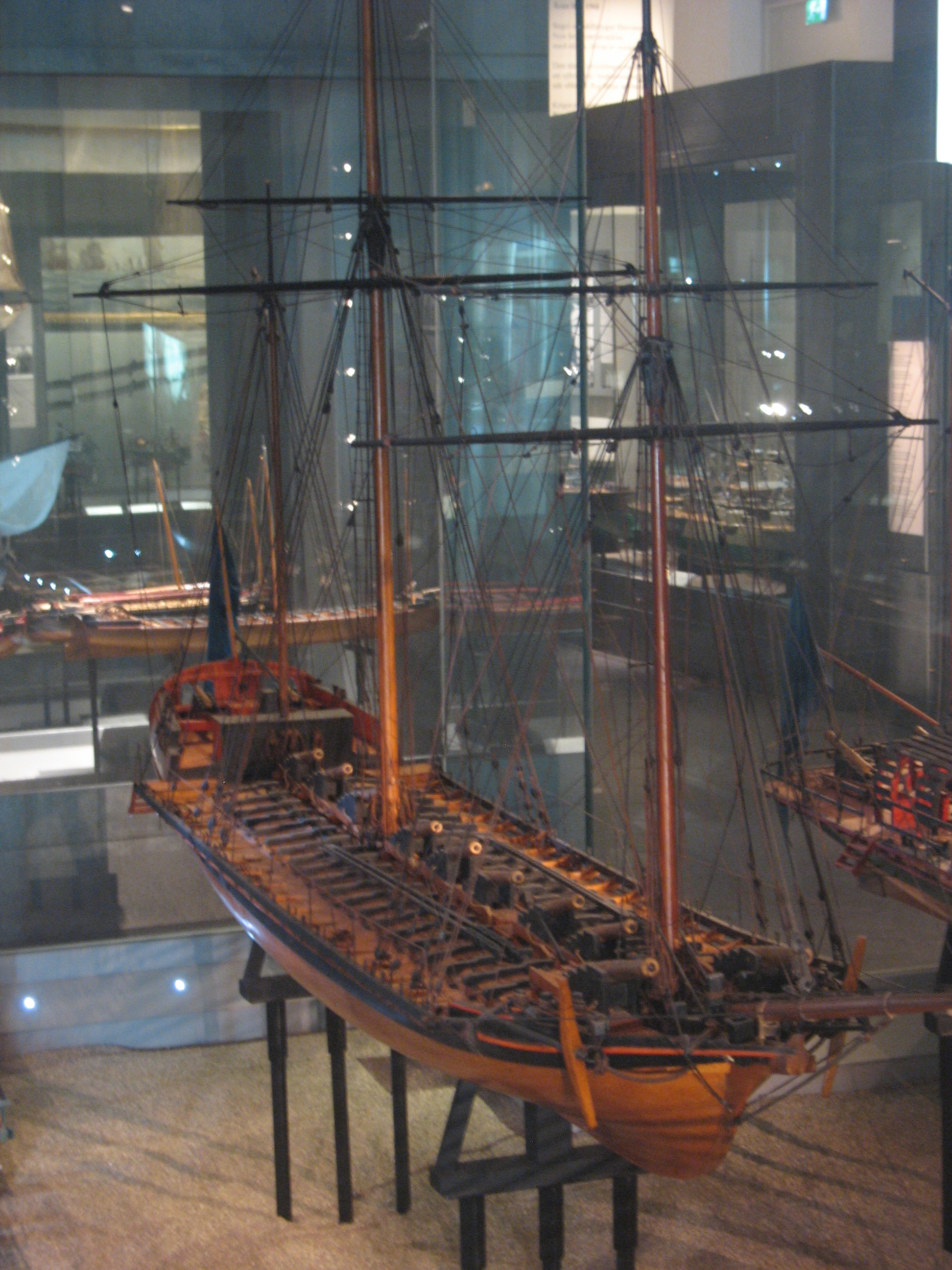

The British had a bruising early encounter with such vessels in 1781, when dozens of small, flat-bottomed Spanish galleys, each armed with a single immense 36-pounder cannon, fanned out from Algeciras to demolish storehouses and workshops in Gibraltar’s dockyard, damage British ships at anchor, and enfilade the main, northward-facing British defensive lines from the west. These Spanish gunboats had been designed by Adm. Fredrik af Chapman, Swedish-born son of two English parents, sometimes hailed as the world’s first naval architect. For his country’s militarily and socially elite Arméns Flotta (literally ‘Navy of the Army’), af Chapman produced a bewildering array of designs for inshore fighting, featuring retractable keels and oars, lowerable masts, and fore-and-aft facing main armament. The most remarkable were his three udemas of 1760-76. Similar to British ship-sloops and brig-sloops in size and sail configuration, each mounted a single row of between eight and thirteen 12-pounders along its centre line, on swivelling platforms that allowed them to be pointed in any direction: a prefiguration of modern warships’ gun turrets.

Af Chapman’s designs were put to the test again, on a much larger scale, in July 1790 at the Second Battle of Svensksund: in terms of the sheer numbers of vessels involved, one of the largest naval engagements in the history of the world. Among the officers of the Swedish fleet that crushed its Russian opponents on that epic occasion were two men who would play key roles, on opposite sides, in the soon-to-erupt French Revolutionary War.

One of them was Capt. Sidney Smith RN, who went on to capture and fortify Normandy’s Îles Saint-Marcouf in 1795. These islets, with defences including two ‘floating batteries’ of Smith’s own design, would become critical to the escape of French royalists into England, the insertion of British spies into France, and the Royal Navy’s blockade of the port of Le Havre. After a period as a prisoner, and extensive service in the Mediterranean, Smith oversaw the evacuation of the Portuguese royal family, treasury, and fleet to Brazil, literally under the noses of French invaders, in 1807: an action that not only materially diminished the risk that Britain would be invaded, but profoundly improved her odds of success in the Napoleonic War on land.

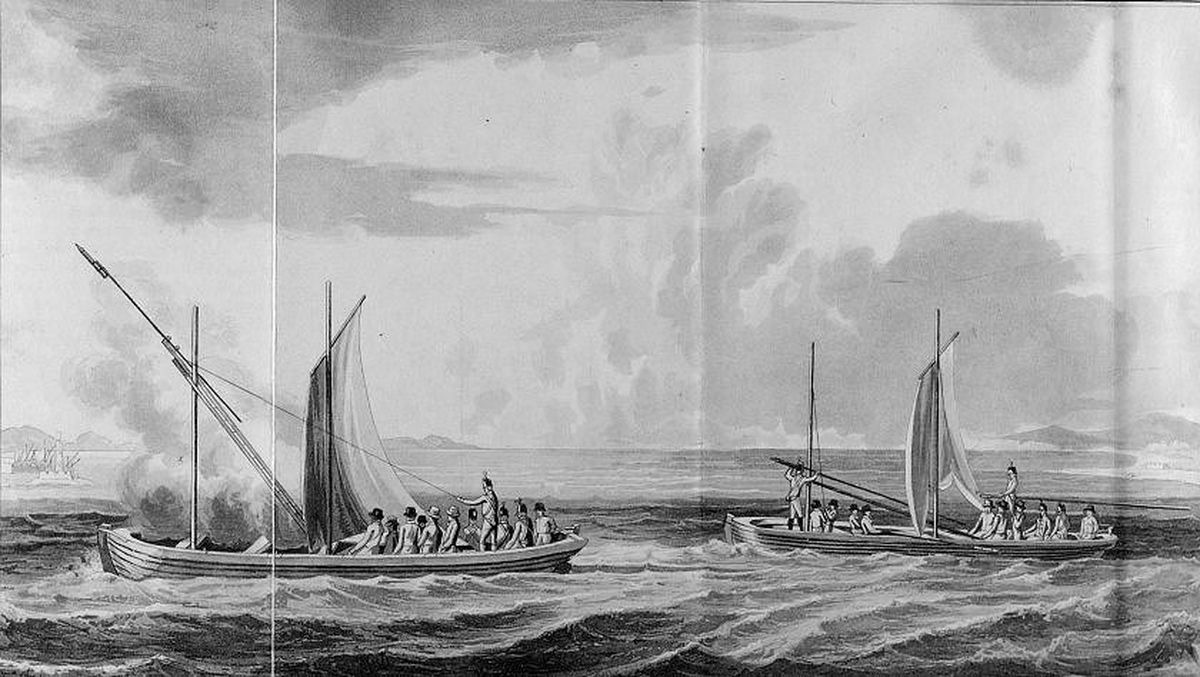

Our other Svensksund veteran, Flemish soldier of fortune A. M. Muskein, would become a leading light in France’s efforts to invade Britain. Indeed, so closely associated was he with the building of specialised invasion craft in the 1790s that, despite their demonstrably Swedish origins, they became known as ‘bateaux à la Muskein’. In November 1796, he was actually on his way to Newcastle with an invasion force, but had to turn back when they mutinied. Then, on the night of 6-7 May 1798, now a captain in the French revolutionary navy, Muskein led fifty of his boats, carrying several thousand troops, to take the British positions on Saint-Marcouf by storm. Arriving at daybreak, the French were sighted 300–400 yards from the southwest shore. When the British defenders began firing roundshot, grape and case from eleven heavy and six light pieces, the French replied with more than 80 guns. Yet, despite their vast superiority in men and artillery, the French were repulsed two hours later, for the loss of at least six boats and up to 1,200 killed, wounded and missing. The defenders, who had suffered just five casualties, also captured one of the invasion boats: an item of considerable intelligence interest, judging by a measured drawing of it that survives in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

Another key figure was Sir Home Popham. In 1793, then-Lt Popham RN had organised the anti-French fishermen in British-held parts of Flanders to help defend their own villages using heavily armed inshore craft, and may have coined the term ‘Sea Fencibles’ to describe these Flemish units. Four years later, leading anti-invasion theorist Alexander Dirom recommended that in Britain, too, ‘ferrymen, fishermen, and resident seafaring people in the neighbourhood’ be ‘taught the gun exercise’ and enrolled on a part-time basis to man gunboats and floating batteries for home defence. Now-Capt. Popham again ran with this idea, and Britain’s Corps of Sea Fencibles was placed on an official footing in March 1798. The negative impact of its existence on Royal Navy recruitment was frequently complained of, but its combat performance was not to be sneezed at. In Weymouth Bay in 1799, some Sea Fencibles and an under-strength company of local Volunteers, armed only with muskets, put to sea to attack a French privateer and succeeded in retaking her British civilian prize. Sea Fencibles’ eligibility and thirst for prize money undoubtedly played a part in such madcap episodes, which were common. And, with the enthusiastic support of Prime Minister William Pitt, an impressive collection of British inshore defence vessels on broadly Swedish lines was launched and crewed.

How the Sea Fencibles would have fared against an immense French invasion flotilla remains an open question – but one that Lord Nelson was more than happy to ask in the summer of 1801. Believing that 40,000 enemy troops would soon land on either side of Dover, he began gleefully plotting a cataclysmic gunboat-vs.-gunboat battle near the British shore. ‘[T]he moment the enemy touch our coast’, Nelson wrote to the Admiralty, ‘be it where it may, they are to be attacked by every man afloat and on shore: this must be perfectly understood. Never fear the event’.

Coastal Defences of the British Empire in the Revolutionary & Napoleonic Eras is available to preorder here.