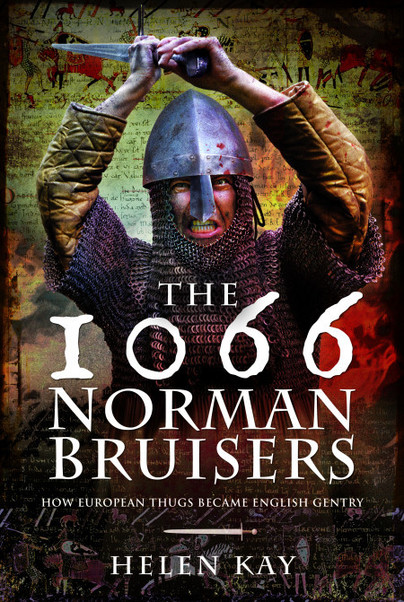

Author Guest Post: Helen Kay

The Black Death: A Medieval Pandemic

In early June 1348 two ships docked at Weymouth in Dorset. They had sailed from the English port of Bordeaux, via the Channel Islands. One vessel was bound for Bristol and just pausing on its journey, but in the meantime both crews disembarked.

Among them were some Gascon sailors who had fallen ill during the crossing and had to be carried ashore. When the sailors were stripped of their clothing, they were found to have strange black cysts about the size of a crabapple in the armpits and groin. The sick men suffered acute pain, with blood and pus oozing from the swellings and dark blotches forming on their skin. Nobody knew what was wrong with them, but within days of landing they were dead. Shortly after they were buried, the rest of the crew began showing similar symptoms and soon followed their Gascon shipmates to the grave.

News of the mysterious malady was suppressed to avoid frightening people off coming into Weymouth to trade, but by mid-June several of the townsfolk were displaying signs of illness. On Monday, 23 June 1348, the disease claimed its first English casualty.

The disease was bubonic plague. Like the COVID-19 virus, Yersinia pestis (the bacterium that causes the plague) probably originated in China. But genetic analysis suggests that one particular strain was responsible for the pandemic known as the Black Death. Starting in a settlement called Laishevo, in the historical Volga region of Russia, the pathogen rapidly travelled west along the trade routes to the Mediterranean and North Africa.

As the plague circulated, other symptoms emerged. Instead of developing a dark rash and hard red boils or buboes that turned black, some victims coughed, perspired heavily and spat blood. In both instances everything that issued from the body – breath, mucus, sweat, urine and excrement – reeked. But those with the respiratory version of the illness died even more quickly, sometimes as little as twenty-four hours after falling sick.

The plague, it transpired, came in three forms. The bubonic type, which produced buboes and internal bleeding, was communicated by contact with an infected person or through minor cuts and sores exposed to contaminated material, such as sheets, rags and clothing. As the bacteria spread from the lymph nodes, the victims’ buboes and skin blackened and their bodies rotted from the inside. The more virulent pneumonic type was transmitted by inhaling plague bacteria. Bubonic plague might also turn into pneumonic plague if the bacteria reached the lungs, or septicaemic plague if the bacteria entered the bloodstream.

Between 1346 and 1353 the Black Death snuffed out the lives of some 200 million people. The plague recurred frequently thereafter, but it would never again cause such havoc. In England alone, there were an estimated two million fatalities – and the toll was so great in some places that there were barely enough people left to bury the dead.

The peasants suffered especially heavily, weakened by successive famines earlier in the century, although the extent of the devastation varied from one village to another. At the manor of Brightwell, in Berkshire, a ‘mere’ 29 per cent of the tenants succumbed to the plague. At Oakington, in Cambridgeshire, the mortality rate was a horrific 70 per cent.

But the Black Death struck arbitrarily, respecting neither riches nor lineage. Even the royal family was affected when Princess Joan perished in Bordeaux on her way to wed the Infante Pedro of Castile, leaving her parents ‘desolated by the sting of this bitter grief’.

Roughly a quarter of all tenants-in-chief – the nobility and gentry who held their lands directly from the king – are also thought to have died of the disease. When a tenant-in-chief expired, a local review was conducted to assess the value of his lands and identify his heir, so that the crown could levy any taxes that were due. The inquisition post mortem for one Cheshire landholder hints at the terrible price the plague exacted.

William Boydell died in late 1349, holding the manors of Dodleston, Grappenhall, Latchford and Handley. The jurors who assessed his estate reported that the value of 120 acres of arable land which William’s servants farmed on his behalf had plunged by two-thirds, ‘owing to the pestilence’. Another 120 acres of land had fallen by the same amount, ‘owing to the death [of] the tenants’, while Dodleston was worth nothing at all.

Today, COVID-19 is blazing its own trail of destruction around the world. But where our medieval predecessors could only call on prayers and quack remedies, we have breathing aids and ventilators. We have also learned from experience. The Black Death brought us the concepts of quarantine and public health. We know that social distancing and self-isolation work, thanks to those who survived the deadliest pandemic in recorded history.

The 1066 Norman Bruisers by Helen Kay is available to order now from Pen and Sword Books.