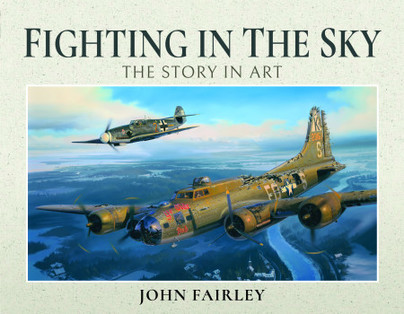

Author Guest Post: John Fairley

Men fighting each other in the sky- to all intents hand to hand like knights of old – was an almost unimaginable experience to all except the few who had actually done it.

And it was to last barely a century from the early days of the Great War.

Today it is almost over, as drones controlled from bunkers in far away places, become the weapons of the heavens.

Words and photographs gave the first indications of the emotions and hazards the first fighting airmen had to confront.

But, within months of the 1914 war breaking out, there were talented painters and artists who determined to try and convey the intensity of fighting in the sky.

Among these pioneers were the two British brothers Sydney and Richard Carline and the Frenchman Henri Farre, who hastened back from Buenos Aires when news of the war arrived. Farre was rapidly commissioned as an official artist to join the French military flyers. He hitched lifts in the rear seats of planes and early on, to his astonishment, saw that his pilot, turning for home after a reconnaissance mission, held the joystick between his knees , while he wrote a letter to his wife.

Farre realised, thus, that he could paint or sketch when he was in the air.

The pictures that emerged so early , already have an air of passion and authenticity.

For all that, he still had to be useful in the air – dropping bombs , with one of them stuck dangerously in the wires of the aircraft until Farre managed to haul it in and throw it down on the trenches below.

The Carline brothers, entranced not only by the tactics of the enemy but also by the landscapes and military emplacements they saw below them, made a point of doing a first watercolour version of their impressions, within minutes of clambering out of their planes.

After the war , when their paintings were first exhibited in London, they were greeted with wonder and astonishment.

When another war came, with spectators on the ground along the English Channel coast able to see some of the contests in the sky, it was the painters, like Paul Nash , who were able to shape in the public mind some sense of the actuality of war in the air.

From Farre’s time on, the painters were able to express what they often felt as joy and exultation, despite the daily dance of death they endured.

Sydney and Richard Carline, who both survived the war to paint the ongoing troubles in Mesopotamia and the Middle East, described how even in the war zone of northern Italy’ they had taken the time to carefully circle down from the sky to try and create a fulsome version of the landscape they saw below, even if the sky was host to the enemy fighters.

Perhaps most surprising is the pilots and artists attitude to bombing.

After the dispensing of huge and indiscriminate destruction from the skies in the Second War – and receiving it too- the public reaction to bombing and the bomber crews was so negative that it took more than sixty years before a memorial was finally erected to the bomber crews at Hyde Park Corner, in London. Even in the Royal Air Force ‘s own club in London it was half a century before a stained glass window was installed to recognise the colossal losses which the bomber crews suffered.

But in the early days of the Great War, the discovery of bombing was greeted with unconcealed delight – even though the first bombs were merely hand grenades chucked down on the trenches from the cockpit.

Farre asked a number of his flyers to describe their experience. In a letter to him, one of them, Lieutenant Partridge, wrote. : Dear Henri, What is my opinion in regard to bombing? I can say only that from the very first trial I have devoted myself to it entirely. The attraction is strong. You will remember our great raids of 1915. The great beauty of departure at sunrise, the crossing of the lines, no more trenches, one flies to the enemy seeking him at rest. With that feeling of absolute detachment from terrestrial things, the spirit free, and without care of bullet or gun, we steer straight to the end in view, drinking in all the beauties of the voyage, and enjoying the ideal sensations to which it gives birth, in anticipation of a perfect accomplishment of the mission in hand.

Partridge enjoyed night bombing even more acutely.

But these emotions were not foreign to the pilots of the massive bombing fleets thirty years later in the Second World War.

Leonard Cheshire, who was to earn a Victoria Cross and establish one of the best known charities of the post war era, described his first experiences of bombing Germany as ‘ gambolling around in utter freedom’ .

The artists too devoted many of their most heroic canvases to the Flying Fortresses and Wellingtons and Whitleys of the bomber fleets. One of Paul Nash’s first paintings of the Second War was Whitleys over Berlin.

In the artists’ stories of Fighting in the Sky there is joy and admiration for all the military flyers. And not just the The Few.

Fighting in the Sky is available to preorder here.