Guest Post: James Goulty

A Brief Guide to:

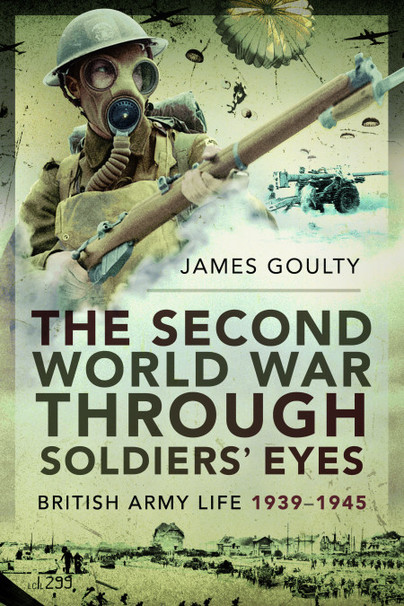

The Second World War Through Soldier’s Eyes: British Army Life 1939-1945

In 2016 Pen and Sword published my book: The Second World War Through Soldier’s Eyes. They will kindly be re-publishing it in paperback during May 2020, which will coincide with the 75th anniversary of VE Day.

The history of the British Army during the Second World War is a vast and fascinating subject, and yet when compared with First World War it hasn’t been covered as much as you might think. This is despite the existence of numerous regimental/unit histories; campaign and general histories; personal memoirs by former soldiers of various ranks; and works by dedicated, academic military historians, including David French. Readers will be able to gain appreciation of the above material from my bibliography. Although the book was based around first-hand accounts and oral histories, it was necessary to consult a much wider range of sources, so as to put these into context.

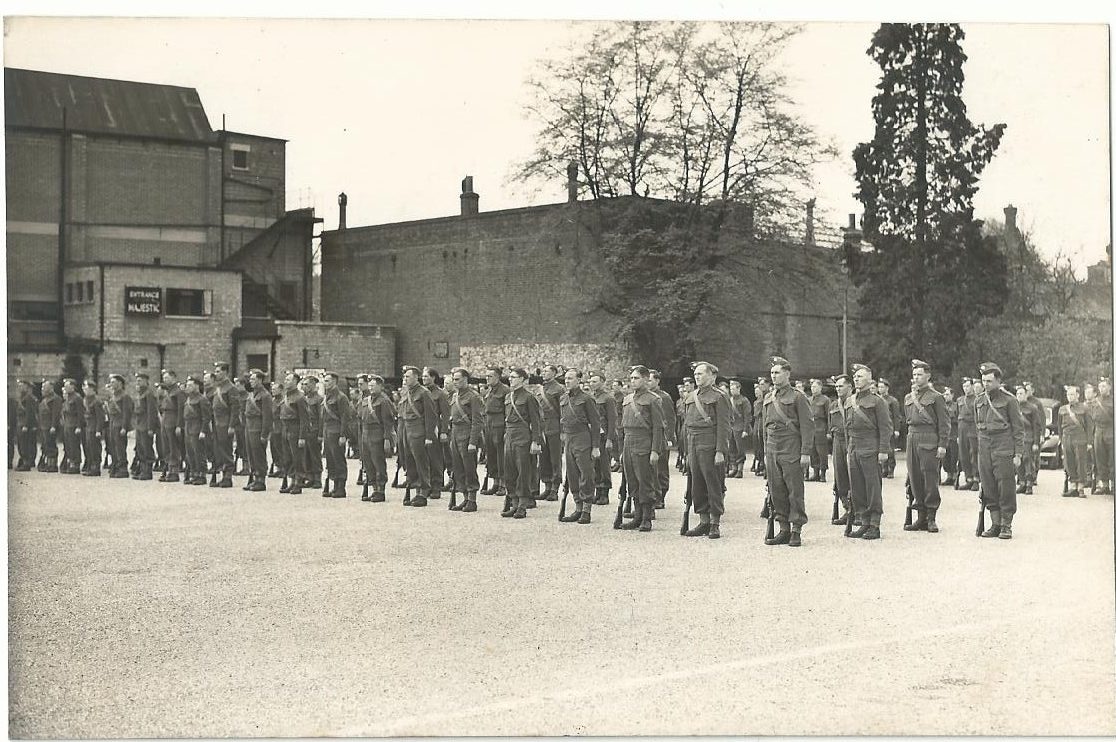

The Second World War Through Soldier’s Eyes attempts to illustrate what the war was like for ordinary British soldiers. It does this via thematically arranged chapters dealing with the following: call-up and training; life on active service; enduring active service (i.e. how did soldiers cope); prisoners of war; casualties and medical matters; and finally a section on demobilisation and the aftermath of the war. As the book makes clear it wasn’t only regular personnel who served, but also Territorials, reservists and conscripts. John Elliot was a Militiaman called-up in late 1939, to serve with 4th Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment, and readers can see his letter from the Ministry of Labour instructing him to present himself for military training.

An upshot of this influx of outsiders was that by 1942 the army became a ‘citizen’s force.’ Having civilians pressed into khaki potentially posed challenges for discipline, morale and training, as not all conscripts necessarily had the right martial aptitude to confront the Axis powers. Neither did they always prove readily accepting of military discipline and traditions. Training had to impart the basics of military service, and was also employed to counter boredom, foster professional pride, and build unit cohesion. Crucially it assisted soldiers in assimilating changes in weaponry and tactics. Notably, from 1941 onwards infantry skills were honed via battle school training, which could at times be brutal.

In contrast, many Territorials had enlisted during the late 1930s because they were motivated to counter Fascism, aware war was imminent, and felt volunteering was preferable to being shunted around as a conscript. Like their Regular Army counterparts, Territorial soldiers were often attracted by the comradeship, sports and social life on offer, albeit many didn’t see themselves first and foremost as soldiers. This spirit was exemplified by the Territorial from 51st Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (Westmoreland and Cumberland Yeomanry), who when asked by a senior officer: ‘How are you soldier?’ replied ‘I am not a soldier sir, I am a greengrocer.’

Men served in various capacities during 1939-1945, ranging from infantrymen to non-combatant roles such as medical orderlies. Likewise, thousands of women performed vital work as military nurses or with the Auxiliary Territorial Service that conducted a host of administrative and logistical functions, often freeing up men for more active deployments. Another significant role of the ATS was in providing women for Anti-Aircraft Command, where they did everything apart from (at least officially) firing the guns. Some soldiers, including Bill Ness from Newcastle, even volunteered for elite units such as the Parachute Regiment.

Initially the army was under-prepared for war, short of key equipment, and had insufficient logistical elements such as engineers, communications and transportation units, necessary for major operations. Overall it lacked direction as well because most combat units were scattered in order to police the Empire. Apart from successes against the Italians in North Africa, the picture was bleak during 1939-1941 e.g. witness the campaigns in Norway, France and Greece. Yet, by 1942-1943 the army was receiving better equipment, and units fought well when properly led.

The chapters on active service and enduring active service consider what life was like in action for the average soldier, and what factors better enabled him to cope and survive the experience. Many didn’t of course, or were wounded, and the chapter on medical matters deals with this, including illustrating the horrendous injuries that modern weaponry could inflict upon the human body. Similarly, the chapter on POWs covers the often harrowing experiences of those officers and men unfortunate enough to have been captured by the Axis forces, in Europe, North Africa or the Far East.

Ultimately the army emerged victorious along with its Allies in 1945. From around 865,000 in 1939, it had, by D-Day (6 June 1944) expanded to over three million men and women, many of whom served in a variety of overseas theatres. Consequently, it was perfectly possible for an individual solder to serve in one or more campaign, and thus effectively have two or three wars for the price of one. According to General Sir David Fraser, typically British troops lacked the tactical sophistication of the German Afrika Korps, with its penchant for mobile operations, but by 1945 they’d learnt the brutal business of war and doggedly pursued the job.

The last chapter contrasts men and women’s differing experiences on returning to civilian life. For some the transition was relatively straightforward, whereas, for others it was more problematic. For example, on returning to Britain in 1945, Bill Titchmarsh, a veteran of the Italian campaign, went to visit his best mate who’d been grievously wounded by friendly artillery fire, and was told by his distraught wife to never visit again, probably because she hated the army after what had happened to her husband. Until his dying day as an in pensioner at Royal Hospital Chelsea, Bill never forgot this, and often thought of his old mucker.

If you’d like to read more about the experiences of men and women who served in the wartime army please look out for:

You can preorder a copy here.

With thanks, James Goulty