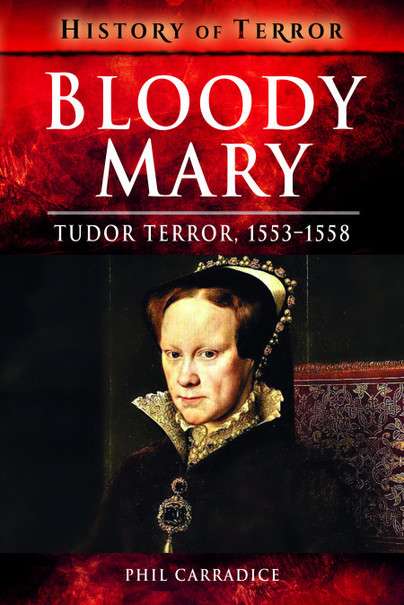

Guest Post: Phil Carradice

Bloody Mary – Mad, Bad or Neither?

Out of the many kings and queens of Britain it always seems to be the “bad” ones that we remember most. They are the monarchs who enthral and entertain us, compelling us to read about their activities, their depredations and their misdeeds, over and over again.

The names and their deeds spring easily to mind – King John losing his jewels in the Wash, Richard 111 and the possible killing of the two Princes in the Tower, Charles 1 losing his head – literally – in an unwinnable war with Parliament.

But none of those almost pantomime villains even begin to compare with the reputation of Mary Tudor. Britain’s first female monarch – as opposed to a Queen Consort – she was the daughter of Henry VIII and a ruler who has been labelled with the sobriquet of Bloody Mary.

Mary was Queen for only five years, succeeding to the throne on the death of her brother Edward in 1553. However there was the little matter of a rival contender to deal with before she could safely take her crown. Lady Jane Grey had been proclaimed Queen by the Duke of Northumberland on 19 July and, to begin with, it appeared that Mary had rather missed the boat.

Never daunted, Mary’s courage, decisiveness and popularity swept her to power and ensured that Jane Grey held the throne for barely nine days. Thousands lined the streets of London to cheer the new Queen to her palace. Yet when she died in November 1558 Mary was probably the most reviled and hated monarch Britain had ever seen.

The reason, of course, lay in her religious policies. Mary, like her mother Catherine of Aragon, was staunchly Catholic. No matter what the threats, no matter what it cost her in comfort and safety, she refused to accept the watered-down version of the Catholic faith that made up her father’s religious settlement. Now that she was Queen she intended to re-instate the Catholic religion to England.

Badly advised and driven by a fervent desire to do what she saw as God’s will, Mary soon began to weed out the heretics. During her reign nearly 300 men and women suffered the traditional death reserved for heretics, burning at the stake, while many more died in prison waiting for trial or execution. Included in this number were Bishops like Latimer and Ridley and the architect of Henry’s break with Rome, Thomas Cranmer.

Burning at the stake was a horrendous form of execution but it was not a form of punishment reserved just for Mary’s victims. Her father had executed over sixty people in this way while her sister and successor Elizabeth continued to send dozens of prisoners to the stake during her forty year reign. The difference was that Mary killed her heretics in a period of just three years.

She might have been Queen but Mary was an unhappy woman. Married to Philip 11 of Spain – a man she hardly ever saw and someone who really did not like her – she desperately wanted a child. So desperate was she that she suffered the pains and, eventually, the ridicule of two phantom pregnancies. She was ill, probably a rare form of stomach cancer, and this undoubtedly contributed to her determination to do what she saw as a mission imposed on her by God. And so, as she suffered and prayed, the flames from the fires at Tyburn and other execution centres grew higher.

Mary’s childhood and adolescence had been fractured and sad. To begin with she was loved and idealised by her increasingly paranoid father. Then, as an accompaniment to the divorce of her parents, she was utterly rejected – along with her mother Catherine.

She was, by turns, kept virtually in imprisonment, brought back into Court and even assigned to Elizabeth as little more than a servant. Always the threat of execution hung over her head. Mary had little love and even less structure in her life – small wonder that she turned to the Catholic faith with such fervour.

In many ways Mary was an unfulfilled, emotionally stunted teenager who never grew out of her adolescent self-indulgence. She wanted, needed, the love of her father and, later, of a solid husband. She got neither.

The burnings brought fear and even hatred of the monarchy. Priests and men like Bishop Bonner – who was known as Bloody Bonner long before the Queen became Bloody Mary – organised parties of heretic hunters to seek out those who did not conform to the re-established Catholic faith.

One of them, “Nine Holes” Drayner, bored nine separate spy holes in the rood loft of his church so that he could watch the congregation at worship. Look away or yawn behind your hand, Drayner would see and the consequences were too dreadful to be considered.

So great was the hatred of Mary that history has overlooked many of the good things she achieved during her short reign. Amongst other improvements she modernised the navy, renewed the coinage and increased crown revenue. She caused new hospitals to be built and improved the education of the clergy. Above all Mary increased the authority of local government.

Mary’s death was a long and painful one, drawn out by Doctors who did not understand either the physical or emotional pains of a monarch who was equally as out of her depth.

The real tragedy of Mary, Bloody Mary as she will always be known, is that her efforts were all in vain. When she died her sister Elizabeth became Queen and apart from a few brief years when James 11 became King there has never been another Catholic monarch of Great Britain.

Phil Carradice, author of “Bloody Mary” in the Pen & Sword History of Terror Series.

Order a copy here.