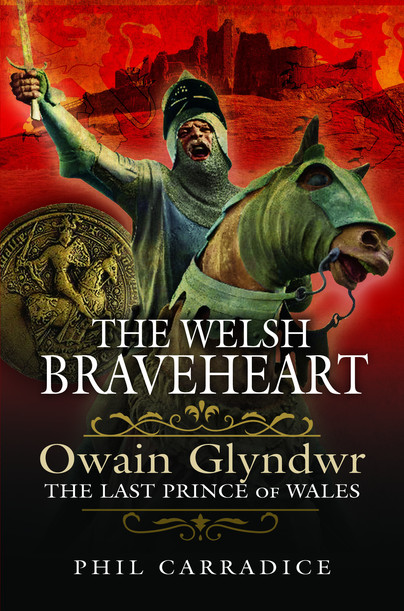

Owain Glyndwr – The Welsh Braveheart

Guest post from author Phil Carradice.

Owain Glyndwr was the last native-born Prince of Wales and, as such, he has been awarded a place of honour in the pantheon of Welsh heroes.

In a recent poll of the Welsh public Glyndwr was placed second in the list of all-time greatest Welshmen. This was then followed this by a ranking of twenty-third in the list of greatest Britons. Not bad for a man who started life as an adherent of the English crown, for someone for whom there is no known likeness or painting and whose rebellion against Henry IV and his son, Henry V, was ultimately doomed to end in failure!

Glyndwr’s date and place of birth are unknown, educated guesses placing his arrival in the world somewhere around 1359. He was the scion of a well-to-do Anglo-Welsh family from the Marches between England and Wales, a descendent of the Princes of Powys and heir to the title Lord of Glyndyfrdwy. Despite his decidedly pro-English upbringing, from an early age he was looked on as something of a national redeemer by the wandering poets and scribes of the country.

The need for a Welsh redeemer was particularly strong in the years after 1282, following the defeat and killing of the Welsh leader Llywelyn by the forces of King Edward 1. In the wake of what now seems more like an assassination than a victory in battle, Edward immediately instigated a degree of ignominy and humiliation for the Welsh people.

The physical manifestation of this oppression can still be seen in the gigantic stone fortresses which, even now, litter the country but its real hurt came in the forced implementation of English law – rather than the traditional Welsh regimes – and by the levying of unfair taxes on the people. The Penal Laws effectively made all Welsh people second or even third-class citizens. The need for someone to lift the burden from the nation was almost religious in its intensity.

Ant yet support for Glyndwr’s rebellion, when it came, was not universal across Wales. He was well supported by many of the uchelwyr, a group of men whose position and status were roughly equivalent to the English squires or minor lords, but his campaigns brought misery and hard times to much of the population. Only with hindsight was his position of national redeemer really accepted by the Welsh nation.

Owain Glyndwr spent the early years of his childhood at the family homes of Glyndyfrdwy on the banks of the River Dee and at Sycharth, some miles away across the Berwyn Mountains on the English border. The house of Sycharth was comfortable, luxurious by the standards of the day, boasting a moat and, of all things, several tall chimneys!

His father died when Owain was young and the latter part of his childhood and adolescence was spent in the homes of the Earl of Arundel and the lawyer David Hanmer. Glyndwr’s mother was determined that her son should receive the best upbringing possible – and service to the English crown seemed to be the best way to achieve this.

Service to the English crown meant taking up arms in the name of the king and Glyndwr performed successfully in several campaigns against the Scots and the French. He was disgruntled, however, expecting a knighthood in return for his work – he received nothing and, emotionally, by 1400 was ready to strike out at those who had seemingly blocked his progress.

His revolt began as an answer to a personal insult from Lord Grey of Ruthin. The dispute was over a parcel of land claimed by both men and eventually seized by Grey. Glyndwr appealed to Henry 1V, the English king, but was met by an off-hand rebuff – ‘What care we for bare footed rascals’ was, reportedly, the response of Henry.

On 18 September 1400 Glyndwr and his supporters – rapidly morphing into a formidable army – sacked and plundered Ruthin. Two days earlier he had been proclaimed Prince of Wales and the longest lasting revolt against the English crown had begun.

The story of the Glyndwr rebellion is the stuff of legend. A guerrilla campaign against English possessions and landlords was backed up by a series of pitched battles. Glyndwr was not always successful in the war but he was feared by the English. Mothers sent their children to bed with the warning that if they did not go to sleep the Welshman Owain Glyndwr would come to take them away! The county of Pembrokeshire, English through and through, even paid him a bounty of £200 to stay away from the fertile lands in the south.

Despite several incursions neither Henry 1V nor his son were able to make much headway against Glyndwr. At times it seemed as if even the elements were against the English forces, snow and rain battering the royal armies and the English soldiers taking refuge behind the belief that Glyndwr was in league with the Devil. Glyndwr the Magician, they called him.

Stories about Glyndwr abound. In one legend or tale, he is walking on the Berwyn Mountains at daybreak when he meets the Abbot of Valle Crucis Abbey. Glyndwr comments that the Abbot is up and about too early. ‘No, sire,’ the Abbot replies, ‘it is you who are too early – by a hundred years.’

The height of Glyndwr’s success came when he seized the castles of Aberystwyth and Harlech. He made Harlech his base, holding court there, and calling a Welsh Parliament at Machynlleth. This was the first specific Welsh Parliament, preceding the current Senedd by 500 years. But it was all too good to last.

Henry V learned many of his military skills, later so effectively used against the French, in his campaigns against Glyndwr and by 1407 the Welshman’s star was on a downward spiral. Nevertheless, he continued to fight on. It cost him his home at Sycharth – burned by Henry – and many of his family who starved to death in captivity. Aberystwyth and Harlech Castles were reclaimed by the English and Glyndwr was last seen alive in 1412.

The disappearance of the last true Prince of Wales was perhaps his most important legacy. He has no burial place, there is no date for his death, and inevitably this has resulted in the legend that he never died. Instead, he lies sleeping and waiting, ready to take up arms again when his nation and people are threatened.

It is perhaps appropriate that the end of Owain Glyndwr should be marked by mystery. It has meant that his legend has only grown in strength and power so that now, in the twenty-first century, he remains a man and a leader for all time – as much the ‘once and future king’ as the mythical Arthur has ever been.

The Welsh Braveheart is available to order here.