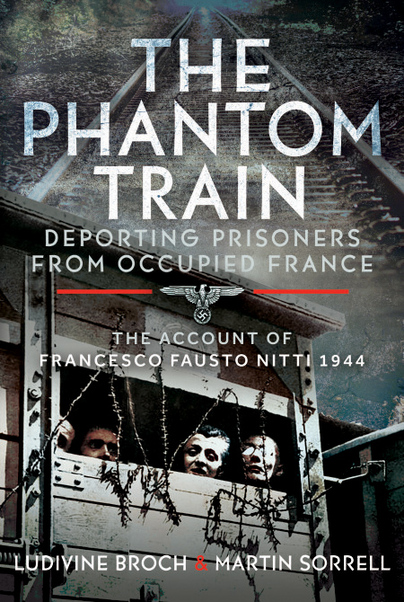

The Phantom Train

Author guest post from Martin Sorrell

THE PHANTOM TRAIN

In the immediate aftermath of the D-Day landings, the Nazi authorities decided to empty as many as possible of the French concentration camps and deport the inmates to Germany. France’s south-west had a considerable number of these camps, including the one at Le Vernet, 80 kilometres south of Toulouse, which was reserved for foreign ‘undesirables’– refugees, political activists, journalists etc. Among them was Francesco Nitti, an Italian anti-fascist who’d survived Mussolini’s jails, fought on the losing side in the Spanish Civil War and finally crossed into France to join in the fight against the German occupiers.

In the first week of July, a large percentage of Le Vernet’s population was removed, taken to Toulouse and loaded into a train of cattle wagons.

Several more prisoners, among them women and Jews, were brought in from nearby jails and crammed aboard the train, which then departed for Dachau. The journey was expected to take three days. In the event it took two months, making it the longest-lasting deportation voyage from France of the Second World War. Why so long? The problem was the state of the railways. By that stage of the war, the network was both heavily damaged and over-burdened. Post-D-Day, the Germans were rushing as many troops and as much materiel as could be spared towards Normandy, and this traffic took precedence over everything else. The railway system was under constant aerial bombardment by the Allies, while on the ground the Resistance was attacking the infrastructure, disabling locomotives, blowing up installations, bridges and viaducts as well as crucial stretches of track.

The obvious route for Nitti’s train was due north from Toulouse, up via Limoges towards Paris and then eastwards. Instead, it headed west to Bordeaux and then attempted to advance along a more roundabout route. It didn’t get far, soon forced back to Bordeaux, where its 700 or so captives were marched off to the city’s Grand Synagogue. There they remained imprisoned until four weeks later they were returned to the train, which had acquired yet more prisoners. It then headed back the way it had come, through Toulouse and Nîmes until eventually, not far from Avignon, it could proceed no further as the track ahead was impassable. So, under a blazing sun, the deportees were force-marched several kilometres to a different line on the eastern side of the Rhône and loaded aboard another train of cattle wagons which then stop-started its way northwards through Lyon to Dijon, where it veered eastwards, until finally it made it to the German border.

But before that, some of the prisoners had died of illness and exhaustion, while others had been removed to be executed. A lucky few had managed to escape when the train made occasional stops to let everyone out, if only briefly. Nevertheless, the large majority of the captives survived to cross into Germany, weak and broken in spirit. Remarkably though, a few had had the strength to escape. Among them was Nitti. Over several days, he and a few others had managed to prise up some of their wagon’s floorboards, and as the train slogged on, they’d lowered themselves onto the track one night and lain motionless until the whole train had passed over them and disappeared into the dark.

Thanks to the daily log which Nitti somehow contrived to keep, not only do we see but we feel what it was like to be trapped for so long inside the Phantom Train, as it’s become known. We get a physical sense of the unspeakable conditions, worsening day by day, inside a wooden box intended for no more than eight horses or forty soldiers. Our nostrils fill with the appalling smells, our bodies register the unbearable heat of high summer in the Midi, our ears hear the cries and moans of 70 near-naked human creatures drenched in sweat and progressively losing the ability to go on as the ordeal continues, sometimes beneath the bullets of Allied planes mistaking the train for a convoy of German personnel, causing injuries and fatalities.

Within four months of his dramatic escape, Nitti had expanded his daily log into the book he entitled 8 Chevaux 70 Hommes (In English, The Phantom Train works better than the literal 8 Horses 70 Men). Nitti’s text was published by a small press in Toulouse run by a Resistance comrade. The story it tells is well known in France, where an Association exists dedicated to the memory of the train’s deportees, most of whom did end up in concentration camps, the men at Dachau, the women at Ravensbrück. Although Nitti’s book has been translated into German, the ordeal of the Phantom Train — such a significant event historically — has remained largely unknown outside France. This translation, preceded by a detailed introductory section, brings for the first time to English-speaking readers the story of another of the cruellest crimes against humanity of the Second World War.

Order your copy here.